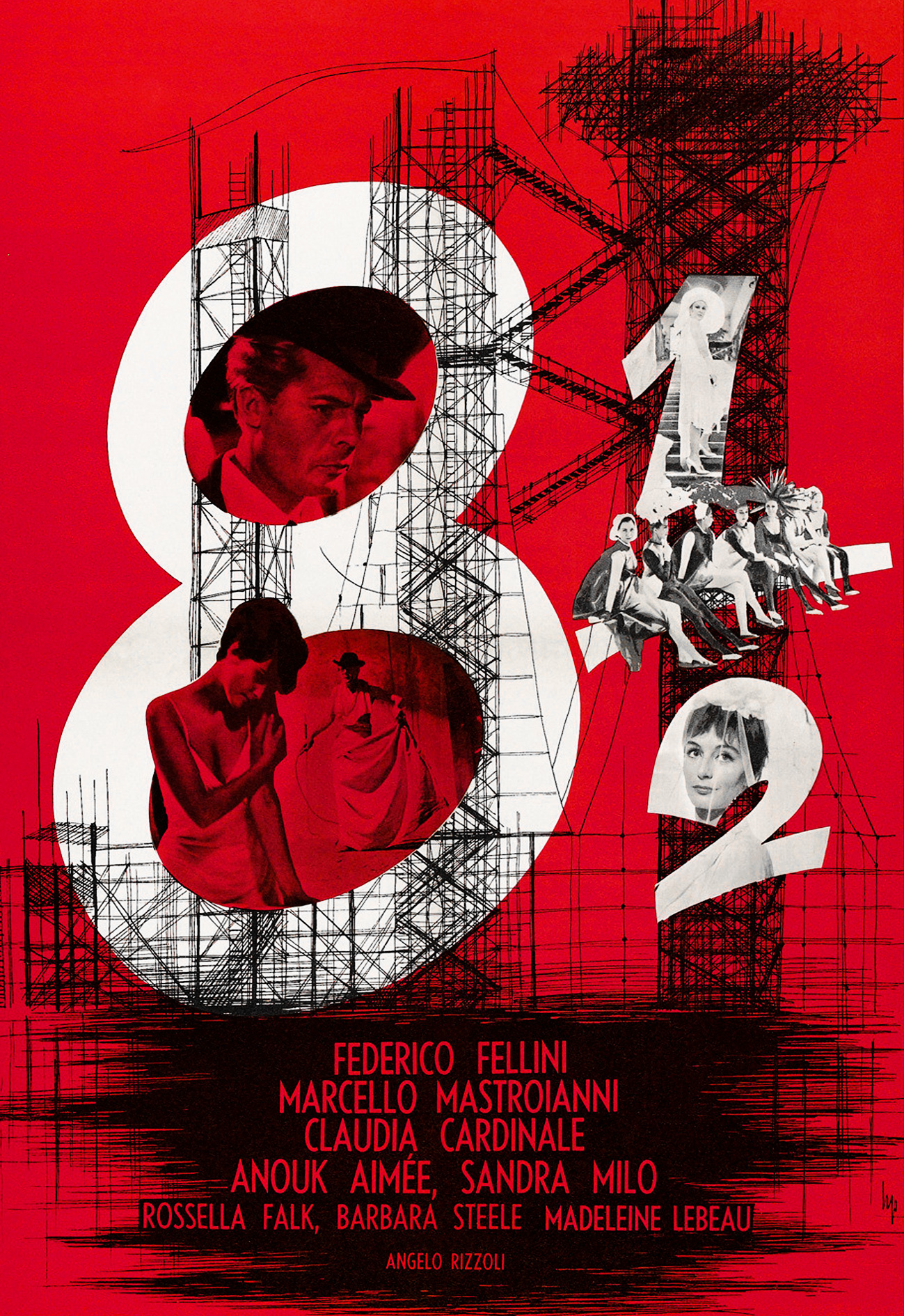

The conventional wisdom is that Federico Fellini went wrong when he abandoned realism for personal fantasy; that starting with “La Dolce Vita” (1959), his work ran wild through jungles of Freudian, Christian, sexual and autobiographical images. The precise observation in “La Strada” (1954) was the high point of his career, according to this view, and then he abandoned his neorealist roots. “La Dolce Vita” was bad enough, “8 1/2” (1963) was worse, and by the time he made “Juliet of the Spirits” (1965), he was completely off the rails. Then all is downhill, in a career that lasted until 1987, except for “Amarcord” (1974), with its memories of Fellini’s childhood; that one is so charming that you have to cave in and enjoy it, regardless of theory.

This conventional view is completely wrong. What we think of as Felliniesque comes to full flower in “La Dolce Vita” and “8 1/2.” His later films, except for “Amarcord,” are not as good, and some are positively bad, but they are stamped with an unmistakable maker’s mark. The earlier films, wonderful as they often are, have their Felliniesque charm weighted down by leftover obligations to neorealism.

The critic Alan Stone, writing in the Boston Review, deplores Fellini’s “stylistic tendency to emphasize images over ideas.” I celebrate it. A filmmaker who prefers ideas to images will never advance above the second rank because he is fighting the nature of his art. The printed word is ideal for ideas; film is made for images, and images are best when they are free to evoke many associations and are not linked to narrowly defined purposes. Here is Stone on the complexity of “8 1/2”: “Almost no one knew for sure what they had seen after one viewing.” True enough. But true of all great films, while you know for sure what you’ve seen after one viewing of a shallow one.

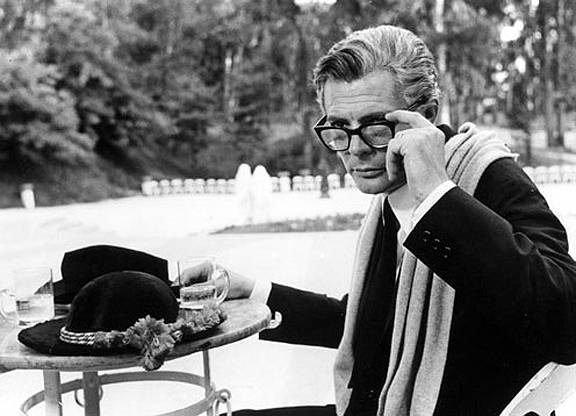

“8 1/2” is the best film ever made about filmmaking. It is told from the director’s point of view, and its hero, Guido (Marcello Mastroianni), is clearly intended to represent Fellini. It begins with a nightmare of asphyxiation, and a memorable image in which Guido floats off into the sky, only to be yanked back to earth by a rope pulled by his associates, who are hectoring him to organize his plans for his next movie. Much of the film takes place at a spa near Rome, and at the enormous set Guido has constructed nearby for his next film, a science fiction epic he has lost all interest in.

The film weaves in and out of reality and fantasy. Some critics complained that it was impossible to tell what was real and what was taking place only in Guido’s head, but I have never had the slightest difficulty, and there is usually a clear turning point as Guido escapes from the uncomfortable present into the accommodating world of his dreams.

Sometimes the alternate worlds are pure invention, as in the famous harem scene where Guido rules a house occupied by all of the women in his life–his wife, his mistresses, and even those he has only wanted to sleep with. In other cases, we see real memories that are skewed by imagination. When little Guido joins his schoolmates at the beach to ogle the prostitute Saraghina, she is seen as the towering, overpowering, carnal figure a young adolescent would remember. When he is punished by his priests of his Catholic school, one entire wall is occupied by a giant portrait of Dominic Savio, a symbol of purity in that time and place; the portrait, too large to be real, reflects Guido’s guilt that he lacks the young saint’s resolve.

All of the images (real, remembered, invented) come together into one of the most tightly structured films Fellini made. The screenplay is meticulous in its construction–and yet, because the story is about a confused director who has no idea what he wants to do next, “8 1/2” itself is often described as the flailings of a filmmaker without a plan. “What happens,” asks a Web-based critic, “when one of the world’s most respected directors runs out of ideas, and not just in a run-of-the-mill kind of way, but whole hog, so far that he actually makes a film about himself not being able to make a film?” But “8 1/2” is not a film about a director out of ideas–it is a film filled to bursting with inspiration. Guido is unable to make a film, but Fellini manifestly is not.

Mastroianni plays Guido as a man exhausted by his evasions, lies and sensual appetites. He has a wife (Anouk Aimee), chic and intellectual, who he loves but cannot communicate with, and a mistress (Sandra Milo), cheap and tawdry, who offends his taste but inflames his libido. He manages his affairs so badly that both women are in the spa town at the same time, along with his impatient producer, his critical writer, and uneasy actors who hope or believe they will be in the film. He finds not a moment’s peace. “Happiness,” Guido muses late in the film, “consists of being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” That gift has not been mastered by Guido’s writer, who tells the director his film is “a series of complete senseless episodes,” and “doesn’t have the advantage of the avant-garde films, although it has all of the drawbacks.”

Guido seeks advice. Aged clerics shake their heads sadly and inspire flashbacks to childhood guilt. The writer, a Marxist, is openly contemptuous of his work. Doctors advise him to drink mineral water and get rest, a lot of rest. The producer begs for quick rewrites; having paid for the enormous set, he insists that it be used. And from time to time Guido visualizes his ideal woman, who is embodied by Claudia Cardinale: cool, comforting, beautiful, serene, uncritical, with all the answers and no questions. This vision, when she appears, turns out to be a disappointment (she is as hopeless as all of the other actors), but in his mind he transforms her into a Muse, and takes solace in her imaginary support.

Fellini’s camera is endlessly delighting. His actors often seem to be dancing rather than simply walking. I visited the set of his “Fellini Satyricon,” and was interested to see that he played music during every scene (like most Italian directors of his generation, he didn’t record sound on the set but post-synched the dialogue). The music brought a lift and subtle rhythm to their movements. Of course many scenes have music built into them: In “8 1/2,” orchestras, dance bands and strolling musicians are seen, and the actors move in a subtly choreographed way, as if they’re synchronized. Fellini’s scores, by Nino Rota, combine snatches of pop tunes with dance music, propelling the action.

Few directors make better use of space. One of his favorite techniques is to focus on a moving group in the background and track with them past foreground faces that slide in and out of frame. He also likes to establish a scene with a master shot, which then becomes a closeup when a character stands up into frame to greet us. Another technique is to follow his characters as they walk, photographing them in three-quarter profile, as they turn back toward the camera. And he likes to begin dance sequences with one partner smiling invitingly toward the camera before the other partner joins in the dance.

All of these moves are brought together in his characteristic parades. Inspired by a childhood love of the circus, Fellini used parades in all his films–not structured parades but informal ones, people moving together toward a common goal or to the same music, some in the foreground, some farther away. “8 1/2” ends with a parade that has deliberate circus overtones, with a parade of musicians, major characters, and the grotesques, eccentrics and “types” that Fellini loved to cast in his films.

I have seen “8 1/2” over and over again, and my appreciation only deepens. It does what is almost impossible: Fellini is a magician who discusses, reveals, explains and deconstructs his tricks, while still fooling us with them. He claims he doesn’t know what he wants or how to achieve it, and the film proves he knows exactly, and rejoices in his knowledge.