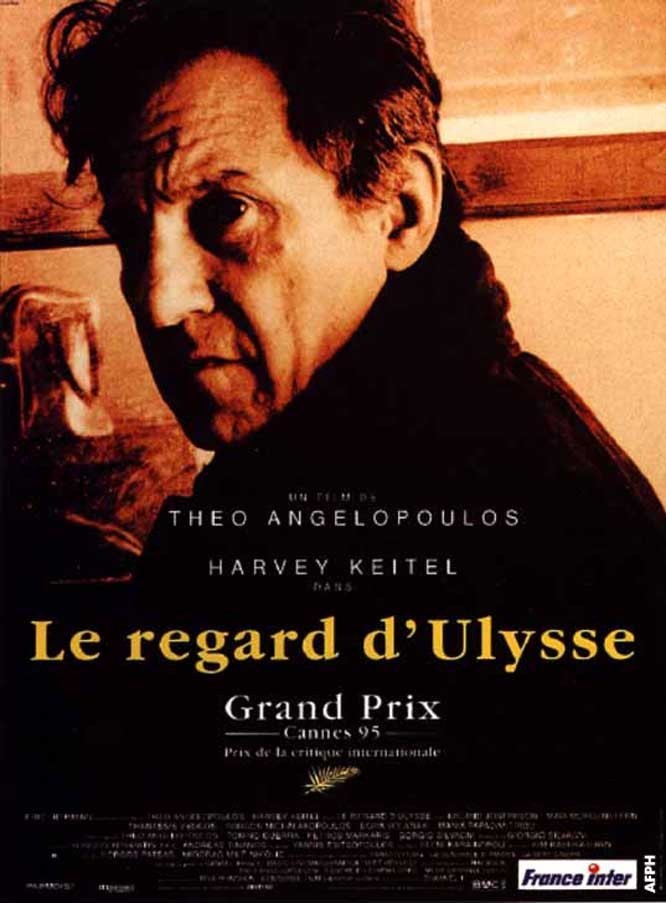

Because it is a noble epic set amid the ruins of the Russian empire and the genocide of what was Yugoslavia, there is a temptation to give “Ulysses’ Gaze” the benefit of the doubt: To praise it for its vision, its daring, its courage, its great length. But I would not be able to look you in the eye if you went to see it, because how could I deny that it is a numbing bore? A director must be very sure of his greatness to inflict an experience like this on the audience, and Theo Angelopoulos was so sure that when he only won the Special Jury Prize at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, he made his displeasure obvious on the stage. He thought he should have won the Palme d’Or, which went instead to “Underground,” by Emir Kusturica, which also was three hours long and also set in the wreckage of Yugoslavia, but had at least the virtue of not being almost unendurable.

“Ulysses’ Gaze” stars Harvey Keitel as a Greek movie director named “A,” who returns to his roots 35 years after leaving for America. He seeks, he says, some rare old film footage: The first film ever shot in the Balkans. His odyssey (for so we must describe any journey in a movie with “Ulysses” in the title) takes him by taxi from Greece to the Albanian border, and then by boat to the cities of Skopje to Bucharest to Sarajevo. (“Is this Sarajevo?” he asks at one point. If you have to ask, you’re in the wrong place.) Along the way there are flashbacks to 1945 and 1946, when as a friend in Belgrade tells him, “We fell asleep in one world and were rudely awakened in another.” You might be tempted to wonder why old film footage would be so important to “A” that he would risk his life traveling unprotected through a war zone to find it. Since Angelopoulos in fact directed this movie about such a man, and filmed it in the very same war zones, he would probably not be the man to ask.

The initial “A” undoubtedly stands for Angelopoulos, but why he chose Harvey Keitel to portray him is a mystery. Keitel is a great spontaneous actor, able to think on his feet and move around quickly in dialect, and here he acts as if someone has injected him with crazy glue. He’s slow, measured, portentous, tedious, and his dialogue sounds like readings from an editorial translated imperfectly through several languages.

There are several women in the movie (the credits call them “Ulysses’ Wives”), and they find themselves powerfully attracted to “A,” a mystery only partly explained by the fact that they are all played by the same actress, Maia Morgenstern. They see him, he sees them, and soon the two of them are looking greatly pained. I was reminded of Armando Bo’s anguished 1960s Argentinian soft-core sex films, which starred his wife Isabel Sarli, whose agony was terrible to behold and could only be slaked in the arms of a man. “A” and the women make love in this movie as if trying to apply unguent inside each other’s clothes.

There are some remarkable images. They are spaced throughout the film at roughly 20 minute intervals. One shows a thin line of police separating demonstrators with torches, and other people with umbrellas. When the torch-bearers press forward, the umbrellas undulate backward, in a scene reminiscent of the umbrella scene in Hitchcock’s “Foreign Correspondent.” Similar crowds with umbrellas stand in squares, and in fields, and along the banks of rivers. One wonders if the umbrellas are important to the shots, or if the extras demanded them.

Another big image involves a huge statue of Lenin, which has been disassembled and placed aboard a barge. (For shipment. . . where? Where is there a demand for used Lenin statues these days?) The vast stone head looks forward, and Lenin’s giant finger points the way, as “A” travels on the same barge. The image is so powerful that even its banality cannot diminish it.

The closing passages of the film have an immediacy; they’re set in the middle of a war zone, and characters important to “A” are endangered. But one can easily think of much better films also shot under wartime conditions, particularly “Circle of Deceit,” shot by Volker Schlondorff during the fighting in Beirut, or Milcho Manchevski’s “Before the Rain,” shot near the fighting in Yugoslavia.

What’s left after “Ulysses’ Gaze” is the impression of a film made by a director so impressed with the gravity and importance of his theme that he wants to weed out any moviegoers seeking interest, grace, humor or involvement. One cannot easily imagine anyone else speaking up at a dinner table where he presides.

It is an old fact about the cinema–known perhaps even to those pioneers who made the ancient footage “A” is seeking–that a film does not exist unless there is an audience between the projector and the screen. A director, having chosen to work in a mass medium, has a certain duty to that audience. I do not ask that he make it laugh or cry, or even that he entertain it, but he must at least not insult its good will by giving it so little to repay its patience. What arrogance and self-importance this film reveals.