For some reason, when Alain Resnais‘ film “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet” was shown at Cannes last May (as one of four French titles in the Competition line-up: the others were “Rust and Bone,” “Holy Motors” and “Amour“), a great many film critics and journalists who should know better wrote that this was Resnais’ “final film.” Not his most recent or his latest, but his LAST one. That’s as silly as taking seriously a satirical item stating that economist Paul Krugman has filed for bankruptcy.

Resnais may be a silver-haired fellow, but he has no intention of retiring. Just because he was born in 1922 (yep, this is one of those essays where YOU have to calculate how old he is — it’ll exercise the part of your brain that has helped Resnais reach the, uh, age he currently is) doesn’t mean he isn’t intent on continuing to tell stories and perfect his craft. He’s working on another film right now. So there.

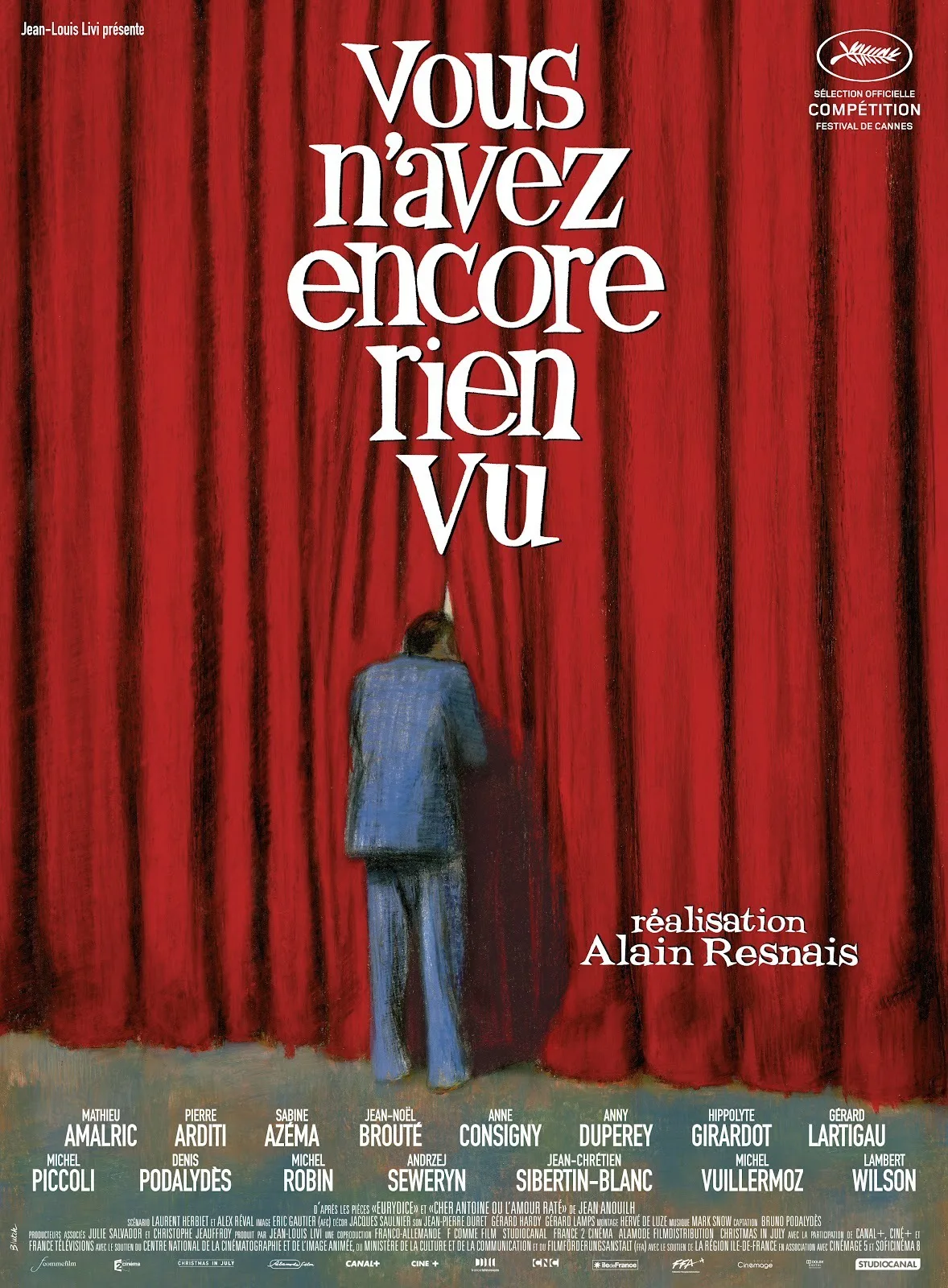

Of course, one could be fooled into thinking this is a “That’s All Folks!” sort of movie because it’s about a dead guy — a theater director — who manages to posthumously summon the actors who performed in his staging of the play “Eurydice” by Jean Anouilh, enlisting them to watch a contemporary staging of the same play by a young theater company. It’s, like, totally, like, “meta.” Metaphorical, metaphysical. It’s also pretty amusing. Resnais relishes eliciting real human emotions, but he likes getting at them through artifice.

The fake snow that falls in his “Coeurs” (adpated in 2006 from prolific British playwright Alan Ayckbourn’s “Private Fears in Public Places”) may just trigger your memory of the first time you ever plopped down in fresh snow and made a snow angel. If, that is, you were in the unlikely grip of inchoate sorrow at the time.

In “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet,” a series of French actors, each addressed by his or her real name, receive a phone call requesting they come to a striking setting. For French audiences, it’s a sort of who’s who, in which members of Resnais’ stock company have pride of place. Every filmmaking country must have a similar collection of actors whose “Ocean’s What-Have-You” presence in the same film is like watching a Rat Pack reunion or a Beatles reunion, were such a thing possible. Or, if you’re a teenager today, Mark Wahlberg and Ted being reunited, say, 30 years from now. You’re so happy to see them sharing the same stage/frame that you may be a bit more indulgent than usual.

French audiences know who these people are. You may not. In which case, there goes one level of “meta” — but there’s the play(s)-within-the-film to keep the ball rolling. “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet” is the sort of film Russian nesting dolls hope is playing when they go to the movies.

If this is the first Resnais film you venture to see, you will surely find interesting things to watch and listen to, but be advised that much of its playfulness is interwoven with culturally specific winks and nods.

That’s okay. A friend recently reminded me that when an all-Chinese “Fiddler on the Roof” played in China, Chinese audiences loved the show but wondered how it could ever play outside China, since it was so inherently CHINESE!

If you have an affinity for thick red velvet curtains parting, for the atmosphere of a murder mystery without any murders, for the poignance of now-aged actors reciting the lines they first performed when their faces were unlined and their vocal cords still young, then much about “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet” may appeal to you.

And if you would rather watch paint dry than see a hip refashioning of a classic piece of French drama, then perhaps now would be a good time to watch another Alain Resnais film instead.

“Alain Resnais is the only director who rings you up to say you’re NOT going to be in his next film,” says actor Lambert Wilson. (You may know him as the Mérovingien in the last two “Matrix” movies or the head monk in “Of Gods and Men” but he has appeared in four Resnais films, including this one.)

Resnais has exquisite manners on set and off. If you ever overhear somebody contending that “All directors are power-mad jerks,” you can set the record straight in a jiffy with these true words: “Alain Resnais is a perfect gentleman.” He also drinks half a dozen cups of coffee (or more!) every day. But his hands are steady, as is his artistic vision. He told the French daily ‘Liberation’ that he was never a user of illicit drugs, “although that was certainly in keeping with my generation,” but that he has always “found the necessary boost in coffee.”

Resnais’ previous film, “Wild Grass” (2009), a relatively light-hearted assemblage of narrative dominos that wobble and topple after a wallet is stolen and somebody finds it, was also shown in Competition at Cannes. At the press conference, a journalist identified herself as being from the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch. I don’t recall her question, but I do remember how Resnais began his reply.

“I am quite moved to be asked a question by somebody from the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch,” he said, in French. “Because for many years I subscribed to your paper in order to read the comics section, particularly Al Capp’s L’il Abner.”

Resnais has thrice won the Prix Louis Delluc, intended to designate the best French film of the year. I don’t put enormous stock in awards, but the Delluc is an interesting prize because it is given by a group of significant French film critics in a country where every publication and broadcast outlet has its own film specialist or specialists and syndicated reviews are unknown. Once drafted, every member of the Delluc jury serves for life, in the manner of U.S. Supreme Court justices.

The Delluc is given by film critics (this past December for the 70th time) in a country where “L’Humanité,” the 109-year-old Communist daily, has four film critics on staff. You know, with salary and benefits. For writing about movies and their place in the world. The historical list of Delluc-winning directors includes names such as Jean Renoir, Jean Cocteau, Louis Malle, Agnes Varda, François Truffaut, Costa Gavras and Claude Chabrol.

All this to say that in the company of talents like that, Resnais has won it three times. In 1966 for “La Guerre est finie,” in 1993 for “Smoking/No Smoking,” his 2-part tour-de-force adapted from the eight stage plays by Alan Ayckbourn known together as “Intimate Exchanges,” and in 1997 (in a tie with Robert Guédiguian’s “Marius et Jeanette”) for his delectably bittersweet lip-synched ensemble comedy “On Connait la chanson” (“Same Old Song”).

Resnais is not a card-carrying member of the French New Wave although his storytelling innovations tended to impress the gents on the New Wave roster. (Godard admitted he was “jealous” when he saw Resnais’ feature directing debut.) Resnais has always asked others to write his screenplays which, in the official New Wave playbook, would be a bit like asking somebody else to brush your teeth.

You may have noticed a classy older French woman who was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar this year. The film in which she gave her astonishingly fine performance, Michael Haneke’s “Amour,” won the Foreign Language Film Academy Award. (It also won the Palme d’Or at Cannes last year, five top Cesars this February and a bunch of other awards, which is pretty good for a subject no Hollywood-style committee would ever have tripped over itself to greenlight: the debilitating, irreversible decline of one half of a loving elderly couple following a stroke.)

Emmanuelle Riva, who turned 86 on the day of the Oscar ceremony, was the oldest individual ever nominated.

Blah blah blah.

Here’s what really matters: Riva’s inner beauty has been evident every time she accepted an award. She takes gracious pains to explain that filmmaking is a collaborative art and that her performance is only one component, made possible by the contributions of cast and crew.

After she made such a speech the Friday before the Oscars when picking up her Best Actress Cesar, the previous year’s Best Actor winner, Omar Sy (Intouchables), offered to hold it for her. She and her towering squire were already headed off stage when Riva leaned back into the microphone to exclaim of her Cesar trophy, “It weighs more than I do!”

Why am I devoting so much space to Emmanuelle Riva? Because hers was the radiant central performance in Resnais’ feature debut, “Hiroshima mon amour,” the movie that made Godard jealous. All these years later, the 1959 film remains a formal and emotional shock. In a somber vein, the film’s structure is as exhilirating as Pulp Fiction’s trippy triptych was when it burst on the scene. Riva plays a French actress who has come to the still-recovering city of Hiroshima after the war to make a film. While there, she meets an excrutiatingly handsome young Japanese man who speaks reasonably good French.

The flippant assertion would be to say that they have sex because, after all, it’s a French movie. But they have sex so they can have post-coital conversations that, in their own way, are more searing than a nuclear-level climax.

The script was written directly for the screen by iconoclastic French author Marguerite Duras, whose own upbringing in French Indochina inspired her 1984 book “The Lover,” (“L’amant”) which was made into a confection of the same name by Jean-Jacques Annaud in 1992.

When Resnais set out to make “Hiroshima, mon amour” (which he followed with the conversation-starting formal oddity “Last Year at Marienbad“) he had many years of experience making short films. Some of them are exquisitely offbeat. One of them, “Night and Fog” (1956), is a certified masterwork. I first saw it in English class as a sophomore at Chicago’s Sullivan High School. I can still tell you exactly where I was sitting that day in 1972.

I grew up in a mostly Jewish neighborhood, and Jewish kids didn’t have to wait until “Schindler's List” to find out about the Shoah. But, although we’d read Elie Wiesel’s “Night” in that same English class, nothing can prepare a viewer for the sight of emaciated dead bodies being bulldozed into open pits, as filmed by the Germans themselves to document the grisly end product of Nazi death camps.

Resnais’ “Night and Fog” lasts only 32-minutes. But actually, it “lasts” a lifetime. It is a primer on unfathomable, methodical cruelty and it is also a compact monument to the power of motion pictures. Brilliantly edited by Resnais himself, the film is comprised of thoughtfully framed images of the camps as they looked a decade after the war, ghastly internal documents filmed “on location” by the Germans, and newsreel footage of prominent Nazis. (In an inadvertent bit of template-produced humor, the IMDb listing for “Night and Fog” tells us that the “cast” includes one Adolph Hitler as “Himself” and that he is “uncredited.” You know what they say: “Uncredit where uncredit is due.’)

In May of 1956, in the now-61-year-old French film magazine “Positif,” Ado Kyrou wrote of “Night and Fog”: “Some films are pleasant, others beautiful, some magnificent. This film is NECESSARY. … This is what war looks like, and fascism. Every man alive on this earth should see this film. And as a result, maybe things will get better.”

If you’re game, by all means take a chance on “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet.” Seek out “Night and Fog” and “Hiroshima, mon amour” and you will, indeed, have seen “something” in the best sense of the term.