Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.

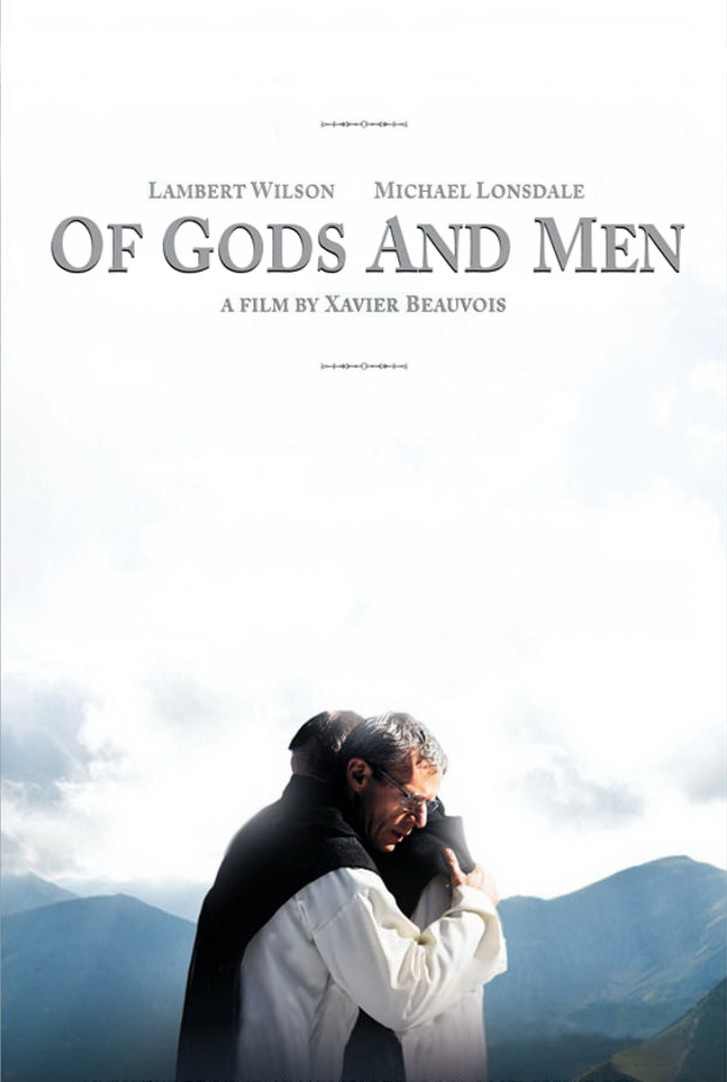

So wrote the French philosopher Pascal in the 17th century, and his words are quoted by one of the monks in this solemn and engrossing film. “Of Gods and Men” is based on an event in Algeria in 1996, when eight Trappist monks were taken hostage by terrorists. The film centers on the fact that the monks could easily have evaded this fate but chose not to.

Every scene in the film involves these monks, and most of the scenes are set in their monastery. Several times a day, they put on white robes and pray and sing in a little chapel. The rest of the time, they tend crops, keep bees, sell honey, treat the sick of the district, eat bread and soup while being read to, and hold community meetings around a table with a candle on it.

They make no attempt to convert anyone to Catholicism. They live peacefully in a Muslim community, attend a service for a child, employ some of the nearby people as workers. There is a deep serenity in their way of life. Although we come to know the monks by face and name, the film makes no particular attempt to focus on their personalities, except for two: Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson), who they have elected as leader, and Brother Luc, played by gentle old Michael Lonsdale, who I first saw in 1962 in Orson Welles’ “The Trial” — that time, too, playing a cleric.

Luc is the doctor, himself old, sick and asthmatic, but seeing countless patients every day and sometimes imparting benevolent advice, as when a village girl questions him about love. Christian is clear-eyed and resolute in his idea of their mission in this place distant from their birthplace in France; they have been called by God to minister to the sick and hungry.

There is revolution in the land. A group of Croatian migrant workers have their throats cut by terrorists. The Algerian government urges the monks to leave, the army offers protection, but Brother Christian refuses; there is no place for the army in a monastery. They will deal with what comes.

The most fraught scene comes when terrorists break in on Christmas Eve, demanding that old Luc come with them to care for a wounded comrade. Christian turns them away, after quoting from the Koran. Their leader, Rabbia (Sabrina Ouazani), is, somewhat unexpectedly, convinced. The next group of terrorists will not be so forgiving. “Of Gods and Men” asks us to admire these monks, whose lives are wholly devoted to good works. There is an uplifting scene when they welcome an old friend with a dinner at which wine is served, the music of “Swan Lake” plays and joy shines from their faces. After some discussion, they follow Christian in deciding to stay at the monastery, no matter what.

The movie has a narration making a sharp distinction between radical Islamic terrorists and the peaceful Muslims who share the district with the monks. But stay. There is another side to the Algerian question, the side of the forcible French occupation and its decades of repressive rule. This land is not France. Technically, which side could be called terrorist?

The film doesn’t raise such political questions, except in one enigmatic sentence by a local official. It focuses entirely on the nobility of the monks in choosing to stay with their vocation and their duty in the face of quite probable death. Did they make the right choice? In their own idealistic terms, yes. In realistic terms, I say no. They have the ability to help many who need it for years to come. It is egotism to believe their help must take place in this specific monastery. Between the eight of them, they have perhaps a century of life of usefulness remaining. Do they have a right to deprive those who need it of their service? In doing so, are they committing the sin of pride?

I found myself resisting the film’s pull of easy emotion. There are fundamental questions here, and the film doesn’t engage them. I believe Christian should have had the humility to lead his monks away from the path of self-sacrifice.