Gloria Steinem, Alice Walker, Susan Sontag, Anne Sexton, Billie Jean King, Shirley Chisholm, and Zora Neale Hurston are just some of the audacious women who were platformed by or played a hand in pioneering Ms., a truly one-of-a-kind magazine. For a publication to be so prolific, to live in the wake of its movement, is a debt that can only be somewhat repaid by carrying on its mission.

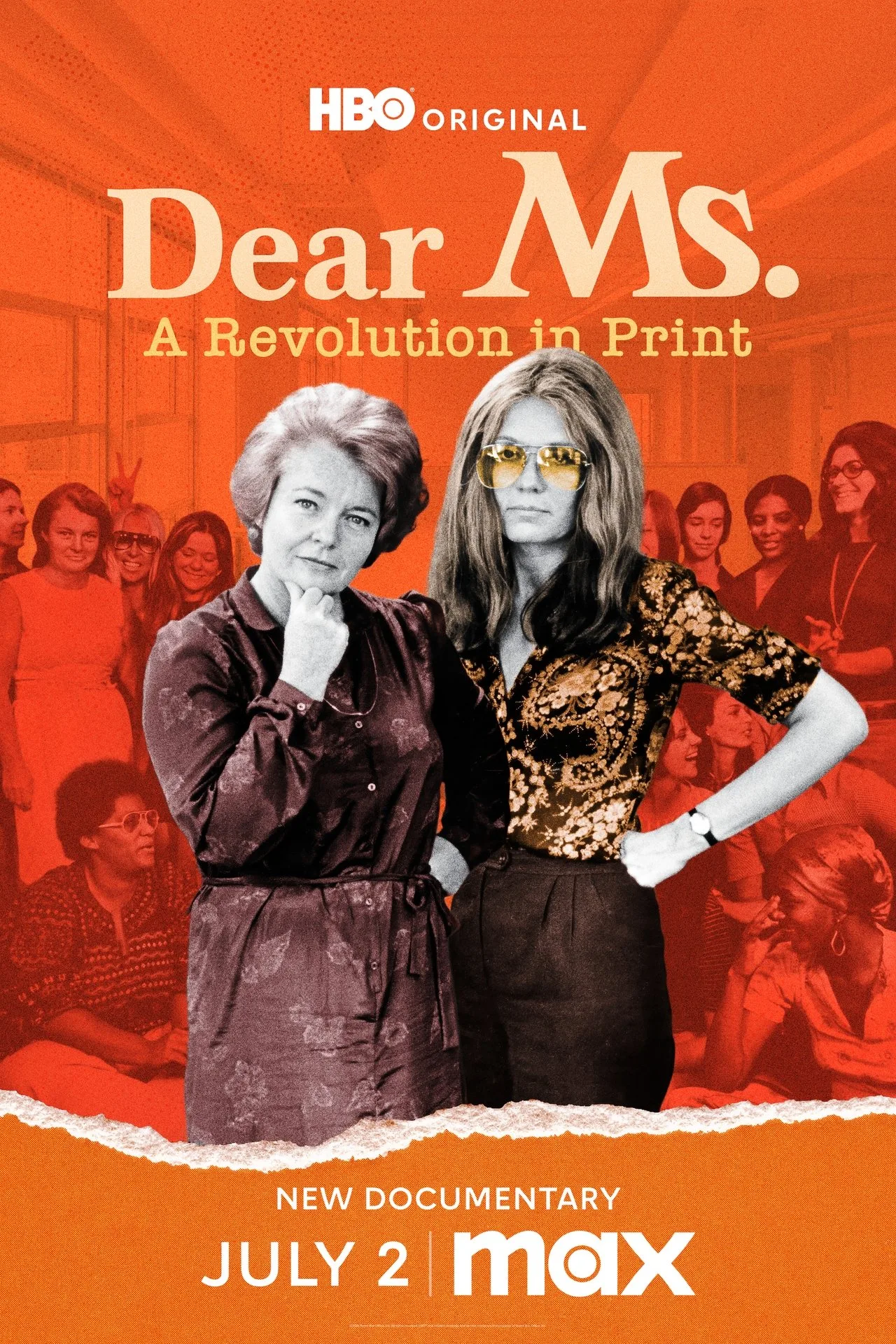

HBO’s “Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print,” now on Max, spotlights and reflects on the 1970s women’s magazine. The feature documentary is divided into three parts by different directors, and it’s unclear why they were assembled in this way rather than as a three-part limited series, something HBO tends to excel at. With each installment led by a different filmmaker, there is some overlap in the curated content. Ultimately, this doesn’t distract from the story. Still, it reflects editorial decisions that differ from the editorial practices of the film’s subjects, the women who always anticipated the expectations of their audience.

The chronology of the chapters strategically showcases the evolution of feminism. Filmmakers are acutely aware of the project’s relevance; they produce a carefully crafted, analytical account of a complex, ongoing social movement. Unearthing the roots and sounding a wake-up call to all genders that the war on femme rights and the female body is still being battled, this movie is a blueprint of how Ms. struck back and made strides.

Part one, “A Magazine for Women,” directed by Salima Koroma, packs its punches—providing grounding historical information, reflective anecdotes, and retrospective criticisms. Grainy archival film photos are decorated with bold, retro animations, and clips of Steinem dazzle the audience, yet the visuals are only part of why. Part one captures what it meant for women in the ’70s to have the ability “to tell the truth and read the truth.” Something that seems so simple was once a radical departure from the status quo.

Koroma’s chapter acknowledges and explores Ms.’s relation to ESSENCE magazine, a publication for Black women, which was founded just a year prior to the launch of Ms.. Although the intention is to highlight and rectify the omission of Black women’s voices and work in the publishing industry at that time, the way each interview presents itself, along with the questions posed to each subject, somewhat pits the two publications against one another. Rightfully so, there is a bit of resentment from ESSENCE’s Managing Editor, Marcia Ann Gillespie, who later became the editor-in-chief of Ms. in 1992.

Parts two and three of “Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print,” directed by Alice Gu and Cecilia Aldarondo, respectively, survey a more specific side of the magazine’s coverage and social impact. “A Portable Friend” admits explicitly at the onset that it’ll focus on men. The Men’s Issue of Ms. was a gamble, even with dreamy Robert Redford gracing the cover. Gu investigates the sexism that Ms.’s Men’s Issue sought to combat, and she, like the magazine, does not shy away from diving into a taboo topic such as domestic abuse.

Aldarondo’s chapter, “No Comment,” parallels the difficulties and differences presented in part one but is possibly the film’s most unresolved yet relevant segment. Provocative pictures and visuals of vulvas set the tone—female sexuality is perhaps the most polarizing subject, even for women. Like Ms. itself, “No Comment,” “reflects and creates what was going on [in the women’s liberation movement].” It simultaneously showcases the successes of Ms. pushing boundaries and the backlash that follows. By rooting itself in Ms.’s “Erotica and Pornography: Do You Know the Difference?” Issue, Aldarondo seeks to complicate further and examine the critique of the female body’s presence in mass media and our everyday lives.

After drawing out ownership of any ignorance held by the Ms. editorial team, it was disappointing that the documentary team did not entirely learn from Ms.’s mistakes. Part one, likely due to Koroma’s direction, displays a diverse cast complemented by diverse archival footage and photos; it does not shy away from asking interviewees critical questions about their potential lapses in judgment. Unfortunately, similar to the excuse made by the Ms. editorial team, “Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print” lacks equitable inclusion of stories and input from women of color throughout its entirety. While it’s understandable that the photos from the past cannot be adjusted, the omission of diverse interviewees was surprising. Ironically, the latter chapters also omit any of the colorful animations.

Like most documentaries, archival footage propels the narrative forward, serving up nostalgia for groovier times and eliminating the need for digital diaries. To hear interviews of Steinem in the ’70s and ’80s sharing the same sentiments on women’s rights as she does today is reassuring of hers and the publication’s values, but concerning regarding our lack of social progress. Despite the film’s focus and deep dive into the inception and pre-millennium phase of the magazine, Ms. and this movie continue the mission and have evolved accordingly.

As many publications scale back or “pivot strategies” on the coverage, the story of Ms.’s origin is a beacon of hope for writers and self-publishers, especially those of marginalized identities. Today, it’s a borderline pipe dream to imagine a major institution like New York Magazine backing a radical, unconventional, and up-and-coming publication. With Steinman’s credibility and Founding Editors Pat Carbine and Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s “go big or go home” mindset, Ms. magazine flourished, completely selling out its first issue.

Newsrooms, too, are no longer what they used to be. When photos of the draft outline for the first issue grace the screen, it’s refreshing to see red ink and classic cursive writing on printer paper. Nowadays, digital drafting is the default. A great majority of publications have pivoted entirely to an online presence, but physical media and its place in our homes are vital. Despite its flaws, “Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print” reminds us that authenticity is essential in acquiring and retaining acceptance and relevance, a message we need to hear now more than ever.