“Velvet Goldmine” is a movie made up of beginnings, endings and fresh starts. There isn’t enough in between. It wants to be a movie in search of a truth, but it’s more like a movie in search of itself. Not everyone who leaves the theater will be able to pass a quiz on exactly what happens.

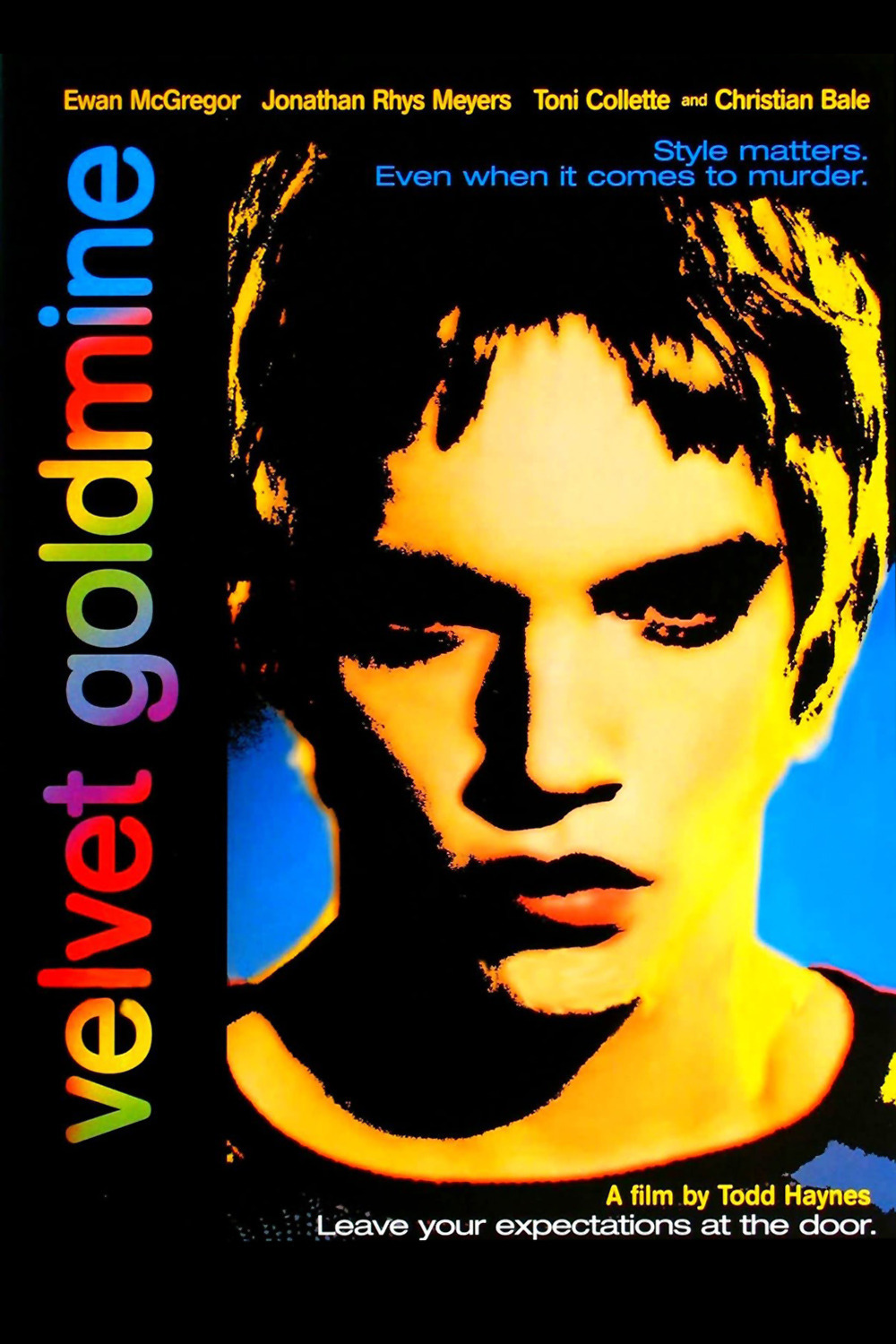

Set in the 1970s, it’s the story of the life, death and resurrection of a glam-rock idol named Brian Slade, played by Jonathan Rhys-Meyers and probably inspired by David Bowie. After headlining a brief but dazzling era of glitter rock, he fakes his own death onstage. When the hoax is revealed, his cocaine use increases, his sales plummet, and he disappears from view. A decade later, in the fraught year of 1984, a journalist named Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) is assigned to find out what really happened to Brian Slade.

Do we care? Not much. Slade is not made into a convincing character in “Velvet Goldmine,” although his stage appearances are entertaining enough. But a better reason for our disinterest is that the film bogs down in the apparatus of the search for Slade. Clumsily borrowing moments from “Citizen Kane,” it has its journalist interview Slade’s ex-wife and business associates, and there is even a sequence of shots that specifically mirror “Kane”–the first interview with the mogul’s former wife, Susan.

“Citizen Kane” may just have been voted the greatest of all American films (which it is), but how many people watching “Velvet Goldmine” will appreciate a scene where a former Slade partner is seen in a wheelchair, just like Joseph Cotten? Many of them will still be puzzling out the opening of the film, which begins in Dublin with the birth of Oscar Wilde, who says at an early age, “I want to be a pop idol.” I guess this prologue is intended to establish a link between Wilde and the Bowie generation of crossdressing performance artists who teased audiences with their apparent bisexuality. Brian Slade, in the movie, is married to an American catwoman named Mandy (Toni Collette) but has an affair with a rising rock star named Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), who looks like Kurt Cobain, is heedless like Oscar Wilde and is so original onstage that he upstages Slade, who complains, “I just wish it had been me. I wish I’d thought of it.” (His wife, as wise as all the wives of brilliant men, tells him, “You will.”) The film evokes snatches of the 1970s rock scene (and another of its opening moments evokes early shots from the Beatles’ “A Hard Day's Night“). But it doesn’t settle for long enough on any one approach to become very interesting. It’s not a career film, or a rags-to-riches film, or an expose, or an attack, or a dirge, or a musical, but a little of all of those, chopped up and run through a confusing assortment of flashbacks and memories.

The lesson seems to be that Brian Slade was an ambitious, semi-talented poseur who cheated his audience once too often, and then fooled them again in a way only the movie and its inquiring reporter fully understand. In the wreckage of his first incarnation are left his wife, lovers, managers and fans. It is a little disconcerting that the last 20 minutes, if not more, consist of a series of scenes that all feel as if they could be the last scene in the movie: “Velvet Goldmine” keeps promising to quit, but doesn’t make good.

David Bowie (if Slade is indeed meant to be Bowie) deserves better than this. He was more talented and smarter than Slade, reinvented himself in full view, and in the long run can only be said to have triumphed (if being married to Iman, pioneering a multimedia art project and being the richest of all non-Beatle British rock stars is a triumph, and I submit that it is). Bowie is also more interesting than his fictional alter ego in “Velvet Goldmine,” and if glam rock was not great music, at least it inaugurated the era of concerts as theatrical spectacles and inspired its audiences to dress in something other than the hippie uniform.

Todd Haynes, the director and writer, is an American whose first two films (“Poison” and “Safe“) were tightly focused, spare and bleak. “Safe” starred Julianne Moore as a woman allergic to very nearly everything–or was she only allergic to herself? These films were perceptive character studies. In “Velvet Goldmine,” there is the sense that the film’s arms were spread too wide, gathered in all of the possible approaches to the material and couldn’t decide on just one.