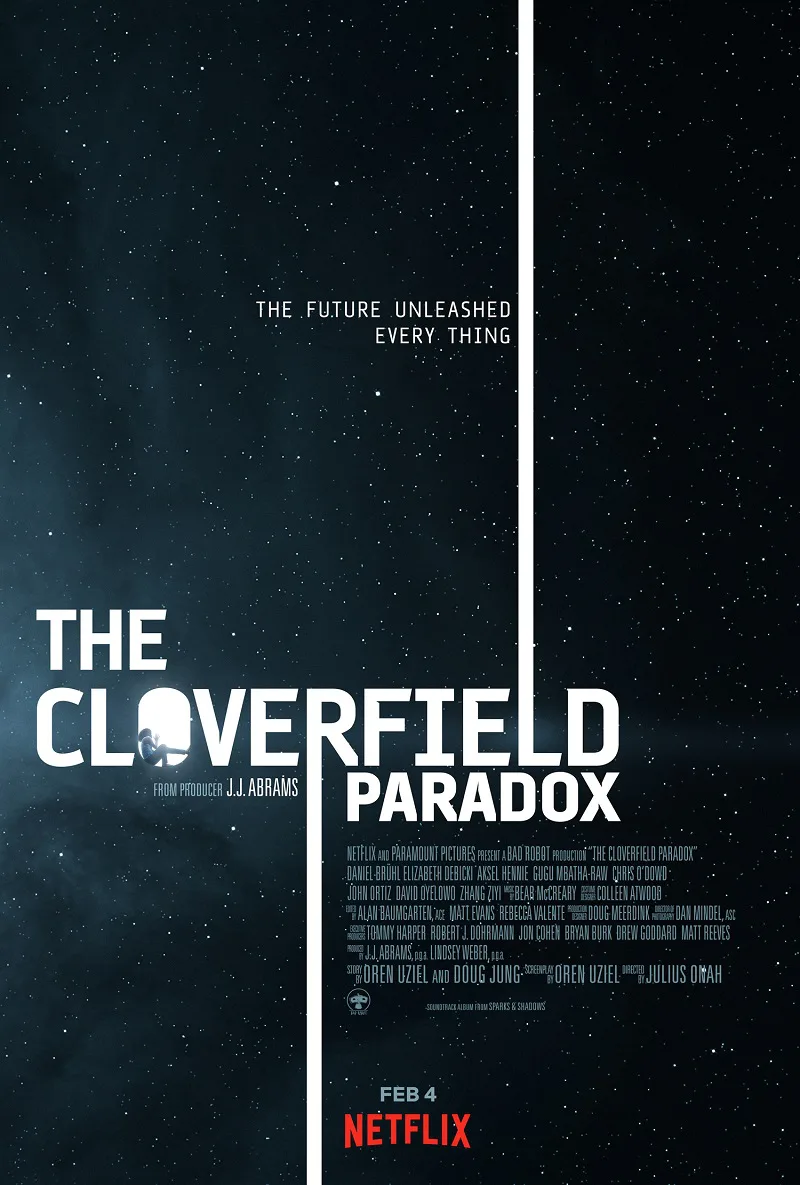

Let’s go out on a limb and predict that February 4, 2018 will be seen as a watershed moment in the history of moving pictures. That was the Super Bowl Sunday when Netflix released the third entry in the popular “Cloverfield” series of science-fiction thrillers—not to theaters, or even with a traditional long-lead buildup to online release, but simply by announcing that it was available that night, by way of an ad that ran during the game itself. Then the service sat back and watched social media light up with near-live reviews by people who were more interested in a new sci-fi film than in the game. By the following morning, reviews like this one started to appear, asking what it all meant—not the movie, mind you, but the implications of releasing it this way.

Turns out there were two masterstrokes here, and they were both about advertising. One was announcing what was, in essence, little more than a new Netflix menu selection during the telecast of North America’s most-watched sporting event, guaranteeing that tens of millions of viewers would at least consider checking it out that night. The other masterstroke was figuring out how to generate excitement for a movie that might’ve barely made an impression had it been released in a more typical manner. “The Cloverfield Paradox” is a bit of a scam job, promising to reconcile entries in a series that have little in common save for a shared genre. It fizzles so badly at the end that you might legitimately wonder if it ever had anything to do with the other two films in the first place, or if it was produced independently of the series and retroactively added.

Directed by Julius Onah and written by Oren Uziel, the film is set during a horrendous dystopian future in which the power grid keeps failing and the Russians are pondering a land invasion of the United Kingdom. Gugu Mbatha-Raw plays Hamilton, a scientist who leaves her doctor husband Michael (Roger Davies) on Earth to join the multinational, multi-ethnic crew of an orbital collider that’s supposed to fire up and solve the world’s energy problems.

Complications ensue, obviously: they’re up there for quite a long time, and their actions somehow remove them from existence in their original reality and deposit them somewhere else, maybe on an alternate timeline. The relationships between people are subtly different, as are their own personal histories. People who should know each other don’t, etc. Meanwhile, back on the original Earth, Michael wonders what happened to his wife and the space station where she once worked, and gets embroiled in a parallel adventure protecting a young girl from various threats, one of which might be making a cameo from another “Cloverfield” film.

Hamilton’s colleagues in orbit include such ace character actors as Daniel Oyelowo, Chris O'Dowd, Daniel Bruhl, Aksel Hennie and Zhang Ziyi (speaking entirely in Chinese with subtitles, a nice touch). Frustratingly generic character writing ensures that none of them makes a strong impression, although the movie does use Hennie’s chararacter, a paranoid Russian, as a human hand grenade, rather like the Michael Biehn character in “The Abyss,” and wisely gives O’Dowd most of the comic relief lines, which he sells but never oversells (his reaction to a moment of stomach-churning body horror is Bill Paxton-worthy).

Onah is a nimble and confident director, jumping right into the middle of action, giving the sci-fi vistas (in particular the orbital platform, which spins like a multilayered gyroscope) appropriately grandiose introductions, lingering on beautiful people and objects just because they’re beautiful, and observing intriguing little details of production design (such as a faux-bagel that assembles itself in a kitchen contraption, and a tube of liquid metal sealant that works like a caulk gun). It’s an offhand style that’s characteristic of post-“Alien” science fiction, where we’re more awestruck by the world onscreen than any of the characters are. There are other compensatory pleasures, including the refreshingly straightforward and comprehensible photography by Dan Mindel (who shot the first two J.J. Abrams “Star Trek” movies, far more flashily) and Bear McCreary’s music, which is reminiscent of Elliot Goldenthal’s majestically bummed out score for “Alien 3” and adds about $10 million to the film’s budget by daring to sound big.

But for the most part, this is a bust of a movie, the kind that would probably have otherwise gotten dumped to theaters in January by a studio looking to cut its losses. And it makes the series feel not like an anthology but a brand name guaranteeing medium-budget genre action with a bit more intelligence than was probably necessary but nowhere near the aesthetic ambition required to really stand out. The second “Cloverfield” entry, “10 Cloverfield Lane,” was a medium-budget art-house sci-fi film, the kind that might’ve shocked everyone in the ’80s by making a fortune at drive-ins and strip malls; it became a hit on the basis of its ensemble acting and its unnerving intimacy—never mind that ending, which confirmed that it was taking place in a different universe from the first “Cloverfield,” a homegrown American answer to a “Godzilla” movie. This one cobbles together scraps from the “Alien” series, “Event Horizon,” “Final Destination, “Solaris” and about a dozen other films, doing a creditable job of seeming as if it has a lot on its mind until the moment arrives (soon into the film, alas) when you realize it doesn’t.

J.J. Abrams, whose name is on the film as a producer, perfected the so-called “mystery box” method of storytelling that promises profound and shattering revelations only to pivot to bromides like, “We should all be nicer to each other” or “Let’s learn to forgive ourselves.” The script to this one falls well within that wheelhouse. I’d like to visit the alternate universe where “The Cloverfield Paradox” is worthy of the stroke of PR genius that launched it.