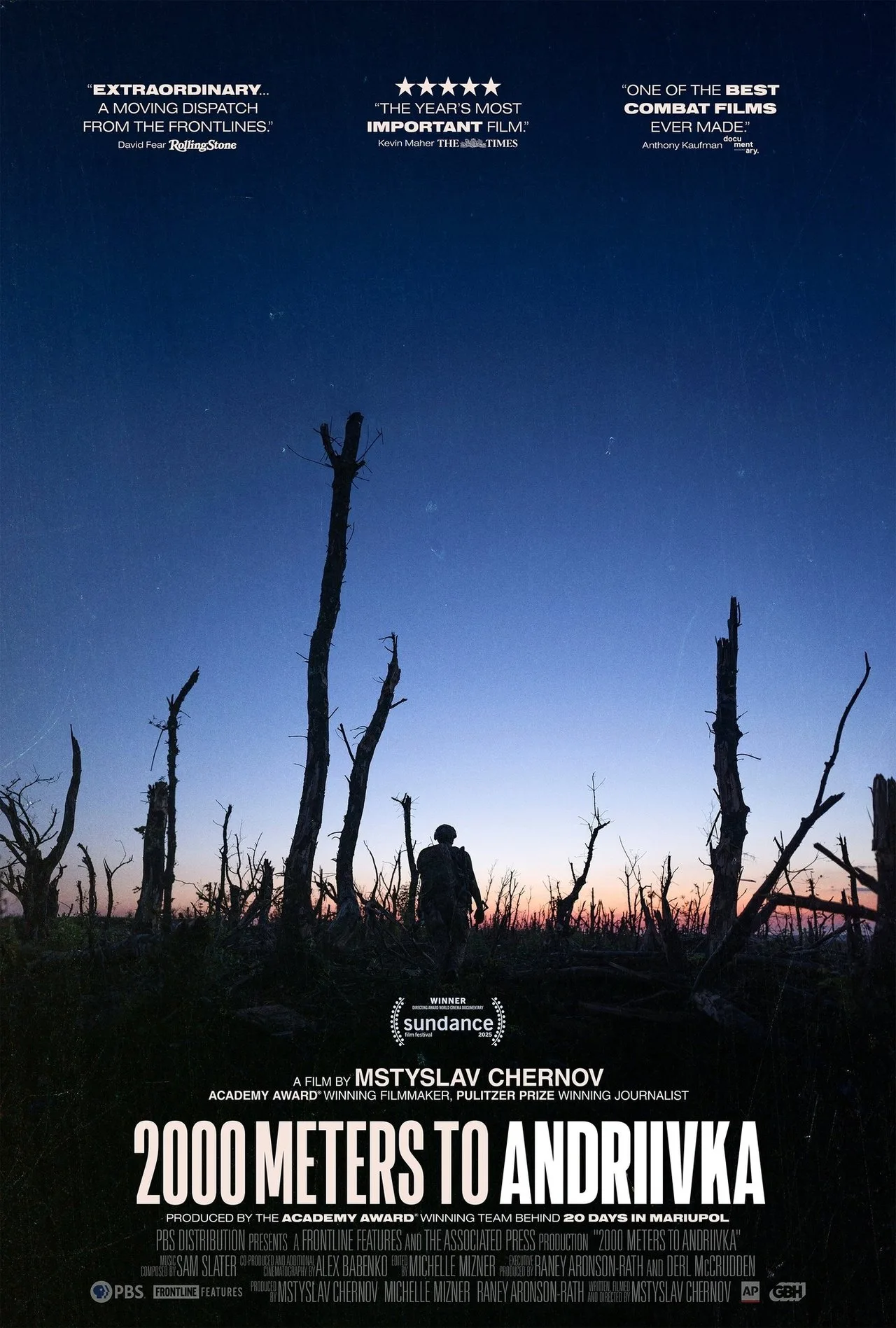

2000 meters. It equals a 2-minute drive, a 10-minute run, or the distance a mortar shell can travel in 35 seconds. But in truth, showcased in journalist-director Mstyslav Chernov’s “2000 Meters to Andriivka,” it’s an odyssey “measured by pauses between explosions.” Fresh off the heels of Oscar-winning “20 Days in Mariupol,” Chernov is in the trenches and on the front lines with this documentary, chronicling the Ukrainian counteroffensive to reclaim the village of Andriivka from Russian occupation. The village, lying in wait on the other side of a narrow strip of forest flanked by minefields, is the 2000 meters by which the troops must traverse.

There are a host of men we meet along the stretch, but namely one who goes by “Freak,” a-22-year-old, baby-faced soldier, and another, the film’s primary subject, Fedya, who leads the counteroffensive itself. Through these men we get most of the film’s pathos. Both were called to volunteer by a sense of duty, but as Fedya clarifies, he joined to fight, not to serve.

As with most war documentaries, learning about the men’s pasts and motivations to join the military is profoundly humanizing, as is watching them interact ordinarily in extraordinary circumstances. They discuss the aesthetics of smoking as bombs land overhead. They laugh with each other while gunfire rings in the background. And then at the drop of a hat, they resume their duty, and not all of them make it.

Perhaps what’s most interesting about “2000 Meters to Andriivka” is that it subverts the expectations of taking a stance on war itself. The horrors we bear witness to, watching men die in staggering short real time, is as anti-war as you can get. But the stories of the men, their dignity, pride, and duty to protect their homeland, and the fervor with which they do it, is somehow pro-war at the same time. The film doesn’t decide, instead prompting you to necessitate the minutiae yourself.

But the primary struggle of Chernov’s documentary is that it leans into the impersonal in an attempt at devastation. It can’t rely on the men as the crutch of the film’s emotion. We meet men who are announced dead seconds later, and helmet cam footage places us into the film as they dodge dead bodies which lie astray on the forest floor. It’s almost overwhelming. But with Chernov’s hushed, monotone narration, it all sours with an overly saccharine tone: an accessorized performance of ruthless indifference.

As we range over birds-eye shots of the woods, which are nearly destitute and barren, “2000 Meters to Andriivka” come most into focus. As Fedya proclaims, Andriivka, their honored destination is not even the village it once was. Villagers, pets, and all signs of life are gone, now ruins and shrapnel. But the declaration lands in the fact that it is their land to rebuild.

Andriivka is being reclaimed on principle rather than prevention. But even with this poignant point in mind, the film feels remiss to not include any sort of biography of the village itself. We know nothing about it other than its current state. But perhaps this is Chernov’s point, nobility over history, affirmed by the film’s opening quote by Ernest Hemingway: “There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity.”