Michael Winterbottom’s film about a romance amid the tumult during the British occupation of what is now Israel is curiously low energy for a story that includes guns, bombs, and a star-crossed love story. It begins with almost seven minutes of voiceover from the title character, recounting the history of the region through the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine that gave the British authority for administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, and it ends as the State of Israel is established in 1948 and the Arab-Israeli war begins the next day.

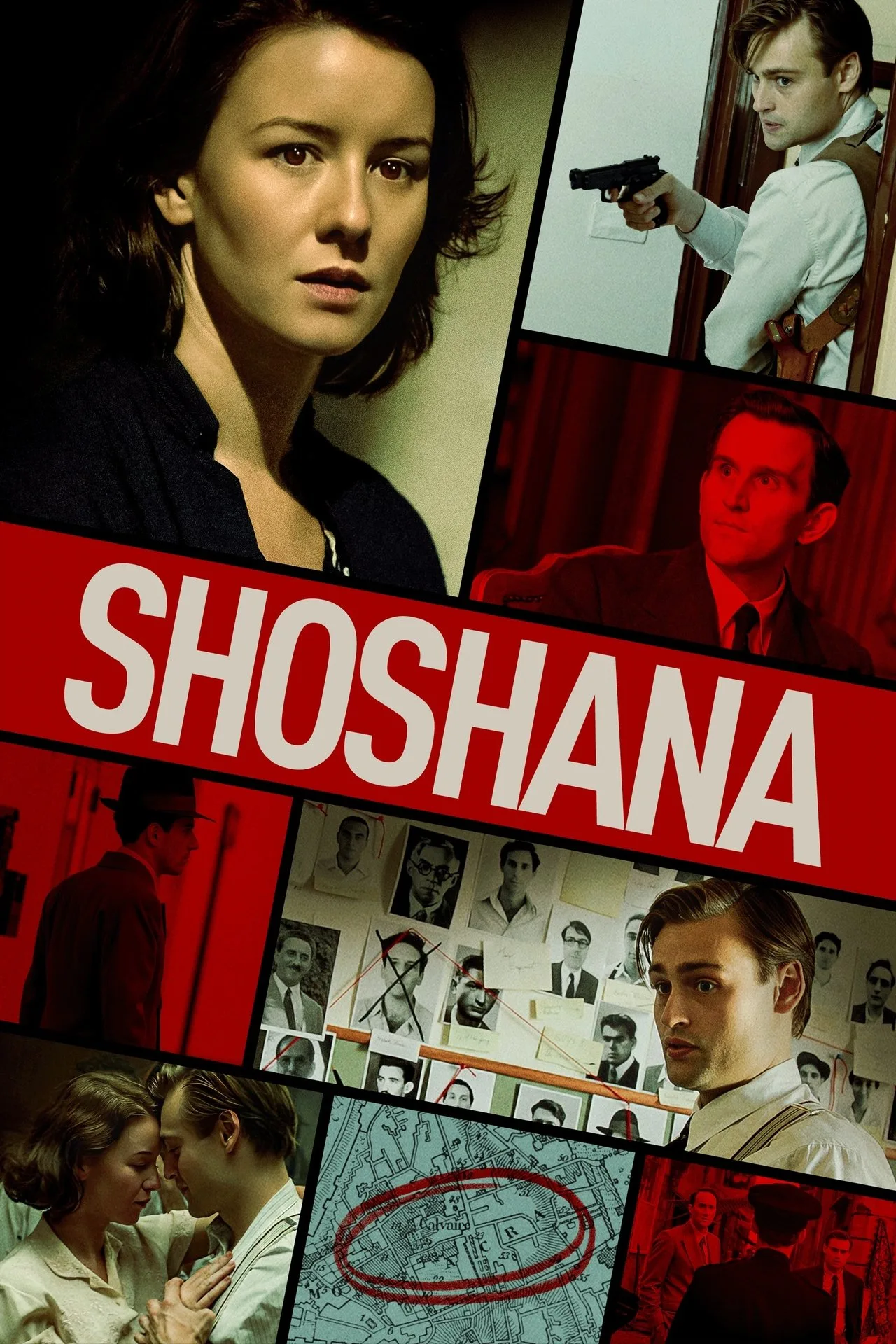

Winterbottom says that he first began to think about making this film when he visited Jerusalem in 2008 for a film festival and read a book about the British Mandate era between the two World Wars. He wanted the film to be about the importance of having “a political argument and be able to disagree with someone and try and find a way through.” He co-wrote and directed the film, inspired by the true story of Shoshana Borochov (Irina Starshenbaum), the daughter of a pioneering Zionist who became a journalist, and her husband, Thomas Wilkin (Douglas Booth), an Assistant Superintendent in the Criminal Investigation Department of the British Palestine Police.

Characters represent a variety of views about the establishment of an independent Jewish state and conflicting views about how to achieve it. As Jewish refugees pour into the area, going from a tiny minority to a huge population, some ally with the more peaceful Haganah, who argued for “havlagah” (self-restraint) in finding a way to end British control. Others support Irgun, who believe that violence is justified to respond to violence from Arabs and to protest British rule. Many who support Haganah, like Shoshana, have friends and family members who are members of Irgun.

The British are there to maintain order. Like the divisions within the supporters of an independent Jewish state, there are different views within the Palestine Police about how to stop the violence. Thomas, who has learned Hebrew and spends time with the community in the new all-Jewish city of Tel Aviv (filmed in Puglia, Italy), believes in working with the Jewish population. His newly arrived superior officer, Geoffrey Morton (Harry Melling) insists that violence is necessary to prevent more violence. He has no hesitation in torturing a prisoner or shooting a suspect for refusing to cooperate.

Shoshana tells us that “most of us saw ourselves as open-minded, modern, free-thinking.” When her editor asks why she is going to a party given by a man who finances Irgun, she says, “Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.” Perhaps that is what Tom is thinking when he attends as well. Or perhaps he just wants to dance with Shoshana. They dance to Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” a song that echoes throughout the film. What does Winterbottom, always very intentional about music, want this to mean? It seems at odds with the tenor of the romance, which is understated, or perhaps a better term would be unstated. The song may not refer to romance but to a yearning for a protector, or a just home that feels safe.

A telling exchange is when Shoshana is getting dressed after they have spent the night together, Tom still in bed. He asks her to stay, and she says she has to visit a new kibbutz. Half joking, he says she will be “sitting around a campfire singing out of tune about utopia.” And then he asks if her group has guns. She says, truthfully but not honestly, “It’s illegal for Jewish people to have weapons, Detective Wilkin.” As a trained investigator, he asks another way: “Are you a good shot?” She says briskly, “Yes, a very good shot.” This conversation is key to understanding the delicate dance around the dangers of their relationship. As careful as they are with each other, though, there is not much they can do about the perceptions of those around them, which become so dangerous that they separate, until they cannot resist coming back together.

Shoshana tells Robert Chambers (Ian Hart), an aide to the British High Commissioner, that the British have made a bad mistake by executing a Jewish terrorist from Irgun, Shlomo Ben Yusef (Gal Mizrav). She does not support Ben Yusef’s attempt to bomb a bus filled with Arab passengers. Her objection is pragmatic. She predicts that hanging him will make the situation worse. (Indeed, today streets in Israel are named after him and he is listed on memorials throughout the country.) Later the anger of the Jewish community is further inflamed when Morton kills one of the founders of Irgun, Avraham Stern (played with deep sincerity by Aury Alby). In an earlier interrogation, Stern said that the British had no legal authority over the area and refused to deny his support for violence. “This is a war, and you cannot fight a war without death,” he said. (Stern is honored in Israel with a postage stamp, an annual observance of the anniversary of his death, and a town named for him in 1981.) When killing terrorists only leads to more attacks, what are the alternatives?

Winterbottom clearly cares deeply about the intractability of the issues and opposes violence from anyone, against anyone. He does not hesitate to show us how devastating, even sickening, the results of violence are. But his characters are understated and matter of fact for most of the film, seemingly accepting each other’s views and the increased attacks as inevitable. There is little chemistry between Shoshana and Tom, and more resolve than passion in the ideas of the Jewish and British characters. Thus, audiences are likely to see this film as more resigned to the inevitability of permanent conflict than providing any insight in how to move away from it. The parallels to current conflicts in Gaza are obvious, but perhaps unintentionally a brief scene with Shoshana talking to new immigrants heading to the kibbutz is a more meaningful commentary on the universal failure of humans to find peaceful resolutions to conflicts over territory. The immigrants have arrived from Kiev.