Some years ago, Oscar-nominated documentary filmmakers Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady were asked what was more important to them: subject matter or character? Ewing answered definitively, “We don’t make films about topics. We are very careful not to come up with a topic and then back into it. It doesn’t matter if you have an in-depth topic if you don’t have amazing characters. Find those who can articulate a journey or who can bring a subject matter to life.”

This approach can be seen in all the films they’ve made, even the ones with dramatic or singular subject matter, like the evangelical summer camp in “Jesus Camp” or New York’s Hasidic community in “One of Us”. These films open up closed systems to often fascinating and alarming degrees, but the approach is full immersion, staying close to just one or two characters. Of course, the observer changes what is being observed, it’s unavoidable, but Ewing and Grady do what they can to counteract. Their character-driven approach is evident in their latest, “FOLKTALES,” which follows three teenagers attending one of Scandinavia’s “folk schools”,

The school is Pasvik Folk High School, in Finnmark, a county in northern Norway, 200 miles above the Arctic Circle. Folk schools were originally established in the 1840s as a way to bring education to remote areas, but to also cohere populations during a period of great flux due to political upheaval and rapid industrialization. The Nordic folk school tradition continues into the modern day. Kids take what would normally be a “gap year” after graduation and spend it at a folk school. Pasvik’s program includes dog sled training, hunting, and “bushcraft” (surviving in the wild). Surviving in the Arctic wild is a whole new level of “survival”. The young adults who arrive at Pasvik come for varying reasons.

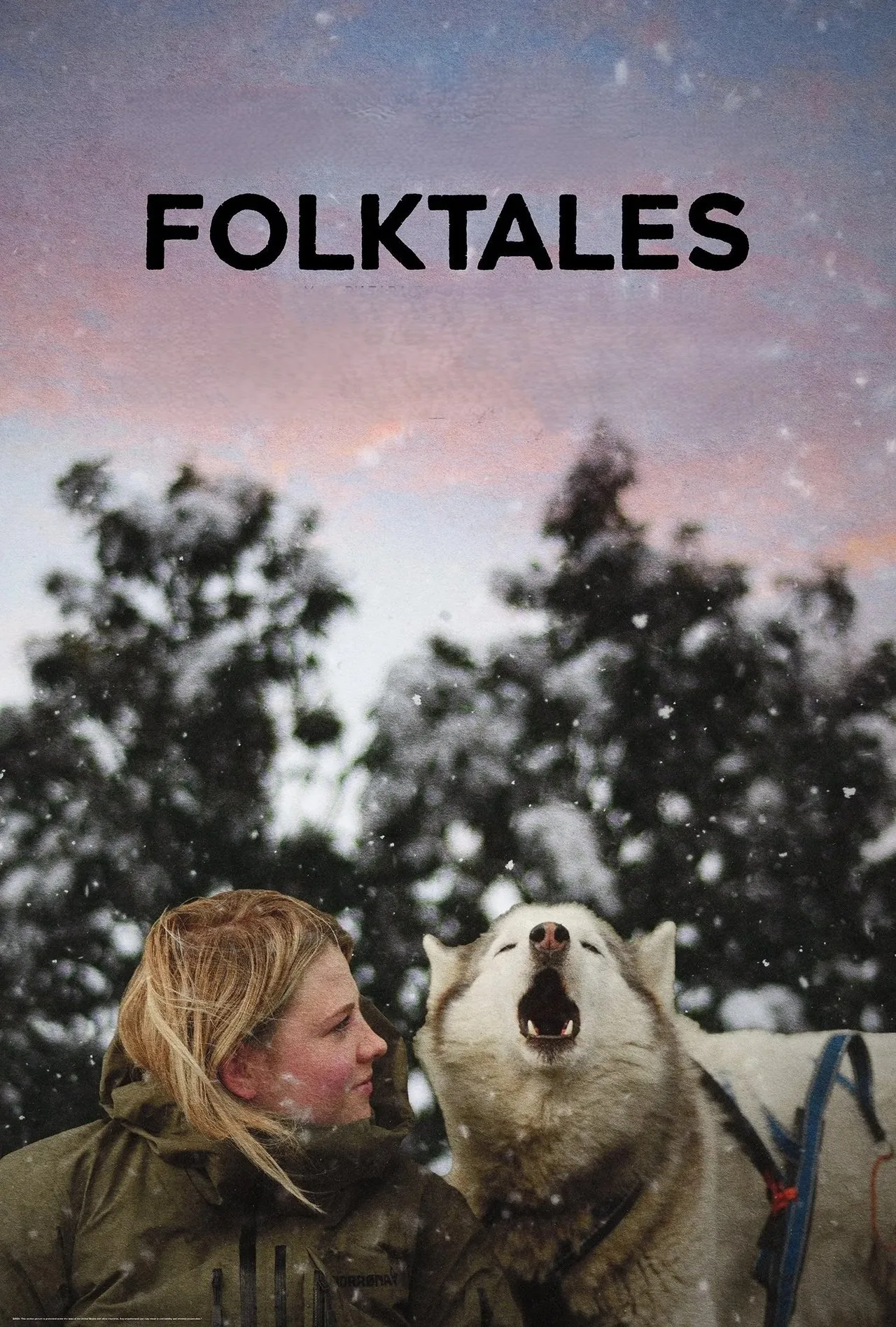

19-year-old Hege says, “I overthink everything.” Her father was killed two years before and she is still grieving. She feels disconnected. She packs way too much makeup to go to an Arctic folk school. Bjørn Tore, also 19, says he doesn’t have any friends, and wonders if he’s “annoying”. Romain, from the Netherlands, speaks of his social anxiety and his struggles with negativity. Each of them will be challenged by their time at Pasvik, challenged by the new skills they will learn, but also challenged by not believing in themselves, wanting to quit, etc. The faculty at Pasvik are motivational but firm about the expectations. Working with the dogs is confrontational for some. Dogs know if you’re feeling insecure. Thor-Alte, one of the dog sledding teachers, says that working with dogs “unlocks something inside a person”. Iselin, another teacher, lectures the kids on how our brains are confused by the modern world and technology. The program at Pasvik is designed, she says, to “wake up your Stone Age brain.”

Ewing and Grady don’t lean heavily on a single “narrative” and there’s almost no sense of “drama,” in the cliched use of the word. What happens is dramatic, but only because people in the midst of sometimes painful transformation are activated by powerful emotions. Ewing and Grady are sensitive to these kids and their journeys. After Hege’s first night camping alone in the wilderness, she admits to Thor-Alte, “My fire was shit.” The next night, though, she’s shown lying in her tent with her dog, campfire blazing. She figured it out. From that moment on, she grows in confidence and resourcefulness. It’s not so easy for Romain. “Sometimes I find being alive is hard,” he says. He gives up on himself. Late in the film, Bjørn and Romain become friends, and the scenes showing the two of them cracking each other up are incredibly moving. They’ve done things they did not know they could do–build a fire, drive a team of sled dogs, but also make a friend. In one of his more poetic moments, Thor-Alte tells the kids, “Give yourself a fire, a dog, a starry sky above you. You can do what you want to in this life.”

The credits list Lars Erlend Tubaas Øymo as director of photography and Tor Edvin Eliassen as cinematographer, and both do essential work. As with all of Ewing and Grady’s films, “FOLKTALES” isn’t strictly linear, mixing the human subjects with the collage effect of their surrounding world, frost-tipped leaves, snowfall on a sled dog’s back, the icy blue eyes of a Siberian husky, sharp rays of the sun across the ice, melting green aurora borealis. Much of what the folk schools want to do is connect the modern day with legends and traditions of the past, putting back together that which has been severed. “Folktales” incorporates Norse legends, of Odin, the Norns and the Three Fates, as symbolized by unfurling red threads wrapping around twisted tree branches, a connection with the past.

“Looking back” doesn’t mean stagnation or even “going” back. Modernity–with all of its progress and innovation–doesn’t provide the nourishment we need to move forward into meaningful lives. Technology, and its evangelists, would have you believe nothing in the past has value at all. “FOLKTALES” suggests that finding the threads connecting us to our collective past is work of great healing and rejuvenation.