At the beginning of “Diciannove,” a young Leonardo (Manfredi Marini) is preparing to leave home at last. As the idyllic sights of Palermo pass by his window, he spends one of his last few moments with his mom pulling a prank on her before laughing it off while she scolds him. He’s still a child, branching out to the adult world on his own. Not even a particularly bad nosebleed can dampen his spirits. He first travels to London to join his sister and her roommate for business school, but finding himself adrift in the greyness of the city, returns to Italy to study literature in the sunnier climate of ancient Siena. But finding a place to call his own and find happiness is just the beginning of Leonardo’s crash course on adulthood. He still has much to discover about himself and the world.

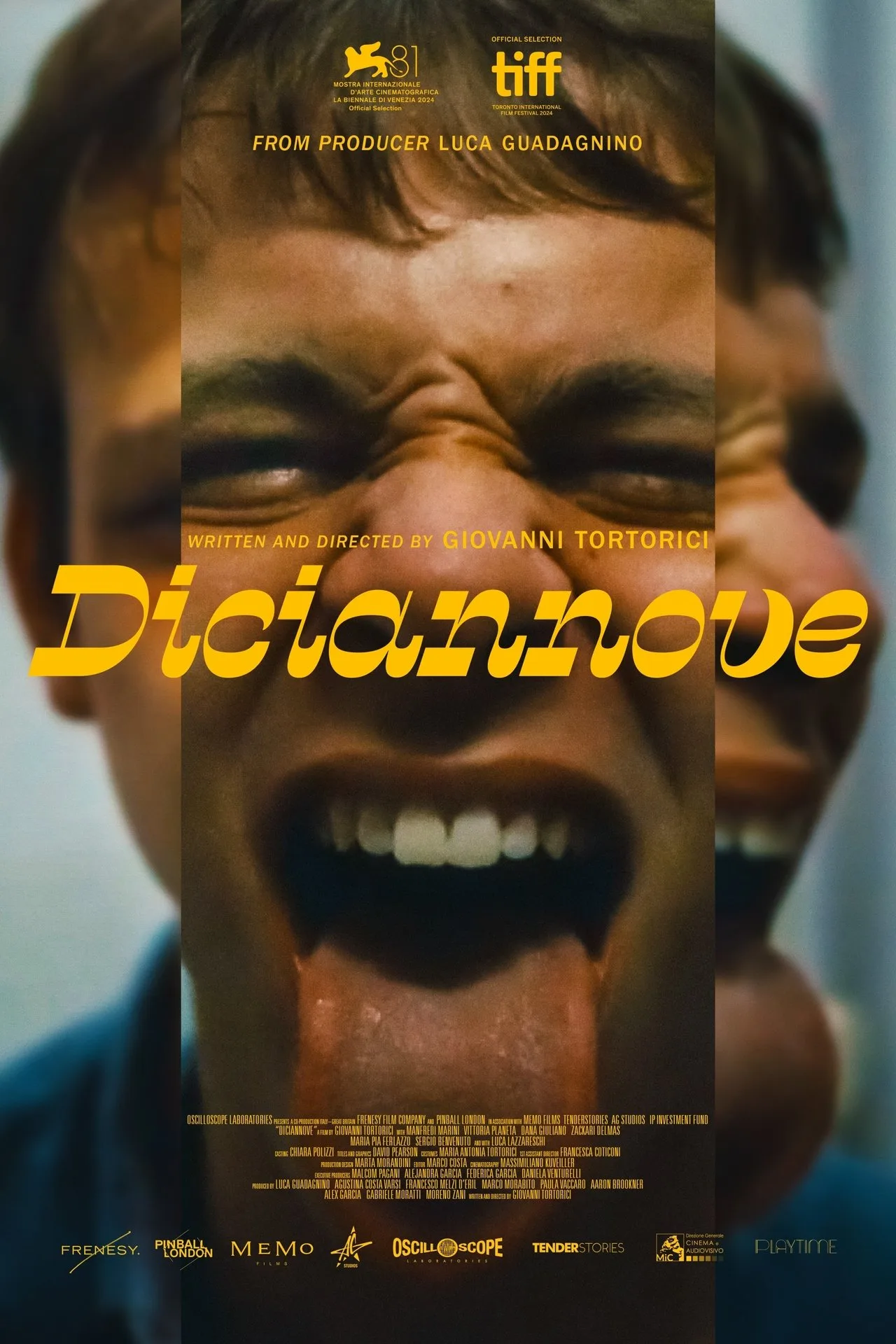

Written and directed by Giovanni Tortorici, “Diciannove,” which means “nineteen” in Italian, plumbs the depths of young adulthood in that strange transition year, from the dizzying highs of feeling invincible on the dance floor to realizing just how much about the world you still have to learn. Leonardo is like a number of freshmen students we may have crossed paths with in college dorms, absorbed in their studies yet not quite at ease with their new surroundings. He is an outsider who either can’t or feels like he can’t relate to his peers. When his sister comes to visit him, she’s horrified by the state of his cooking plate and mess, the tell-tale sign of a young adult learning to clean up after themselves when their mothers aren’t around. In essence, Leonardo is undergoing a second adolescence: testing his boundaries and pouting when things don’t go his way.

Tortorici’s feature debut sports a messy and erratic visual style, playing up Leonardo’s uneasy wobbly steps into adulthood. Tortorici and cinematographer Masimiliano Kuveiller mash together alluring warm shots of Italy to contrast the chilly scenes in London, dreamy architectural tours opposite Leonardo’s drab apartment, and inserting experimental flares like random pauses or shots, animation, use rapid fire editing between Leonardo and his professor to emphasize the intensity of their exchange, blur out Leonardo when his sister asks him about his friends when he is hiding the fact that he has not made any in Siena, or slowing scenes down with intertitles stepping in for dialogue and dramatic orchestral music to accompany a drug score.

At times, it’s almost painful to watch Leonardo’s youthful naivete bump into the walls of reality, drowning in his own insecurity and ennui, and resort to childish actions in order to comfort himself through failure. As a response to not fitting in with his generation, Leonardo develops a fondness for classic Italian literature, holding onto conservative ideologies in his search of morality and order while hypocritically indulging in the same behavior he looks down on. He wrestles with his burgeoning queerness, looking longingly at a younger teen boy and getting turned on by a public masturbator, while later avoiding the well-meaning classmate trying to invite him out, and still fantasizing about (or trying to fantasize for the sake of normalcy) the occasional naked woman.

Loosely based on the director’s journey to finding himself, “Diciannove” may test the limits of how long a viewer would like to revisit teenaged angst in a self-imposed exile, but Tortorici’s creative approach to the subject keeps the movie feeling lively. Newcomer Marini carries the alienated mantle of disaffected youth well, pouting and looking longingly at the world his character has yet to understand. As he recoils from peers and stands off against professors who just don’t understand, Marini holds his character’s contempt in his eyes and his unhappiness is plain for all to see. Leonardo romanticizes the past with no real eye towards the future, bouncing around cities unfocused like a fog, stuck in-between sunshine and rain. He is hungry for sex but unwilling to put himself in rejection’s way. It’s a messy kind of impotence, causing him to fall deeper and deeper into the literary world of 19th century Italy, that will bring him no closer to anyone else in the present. If Rome wasn’t built in a day, neither is growing up in one year possible.