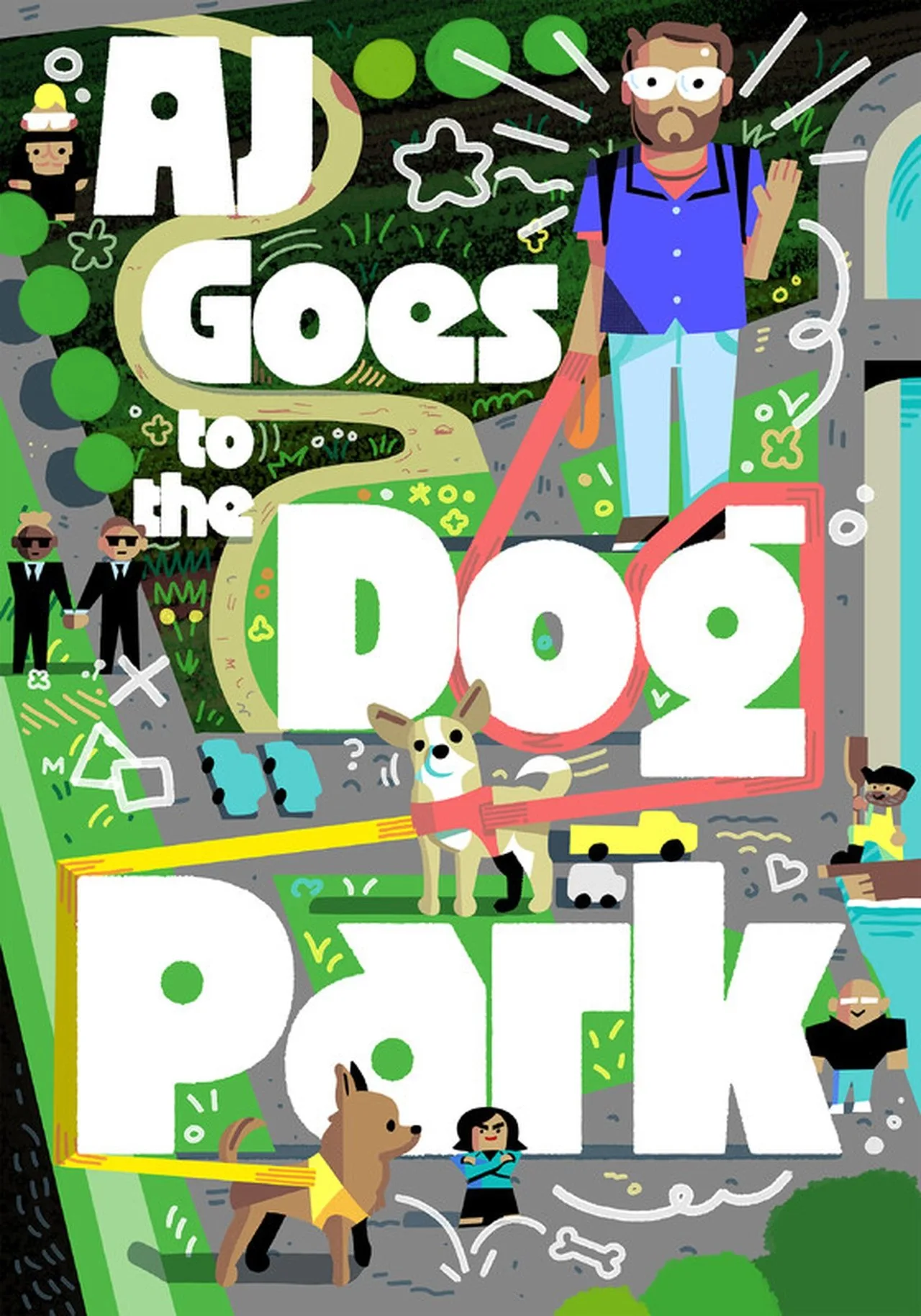

“AJ Goes to the Dog Park,” about a man who decides to run for mayor of his small North Dakota town, feels like a live-action cartoon for a reason: the writer and director Toby Jones has worked on animated shows, including “OK KO: Let’s Be Heroes,” “Regular Show,” and “Shape Island.” It has a lot of the flaws that are common to super-low-budget movies produced outside of the system, such as it is, including hit-and-miss performances and a look that falls somewhere between a “Saturday Night Live” short and a student film.

That’s unfortunate, because there’s something genuinely liberating about Jones’ script, which is so free-associative, goofy, and surreal that it seems constantly in danger of falling apart—and sometimes does. A strong aesthetic might’ve saved it. A cartoonish story needs cartoon visuals, and if they’re striking enough, it doesn’t matter as much if the laughs are inconsistent and other elements don’t quite work, because there’s always something wonderful to look at. Even the Dada-esque comedies that used to be common in the 1930s and ’40s that had fairly plain visuals turned plainness to their advantage, as when a framed portrait painting in a Three Stooges short not only comes to life, but becomes a portal for the Stooges to escape into, with the subject moving aside to make room for Curly. That zero effort was made in the early part of the shot to convince us that the painting was actually a painting, rather than a guy staring through a rectangular hole in the wall that has a frame around it, makes it all funnier somehow.

I digress. The title character, played by AJ Thompson, works at an unspecified business owned by his dad (Greg Carlson). Although the dad is balding, he looks to be roughly the same age as AJ, but in flashbacks, he has a full head of “hair” that’s a deliberately terrible wig. AJ is upset when he goes to the local dog park one day and discovers that the mayor (Crystal Cossette Knight) has turned it into a “blog park” filled with people on laptops, blogging. If you’re thinking this seems out-of-date, well, yeah—and the movie knows it’s out-of-date. Apparently the mayor has been wanting to turn the dog park into a blog park since 2004.

AJ decides to run for mayor and unseat the office’s current occupant so that he can turn the blog park back into a dog park. He’s a man on a mission that he believes is just. But the movie is pretty clear about the fact that he’s bored with his boring job and his boring life and would rather run for mayor than take over the family business, whatever it is. He is also just stuck in a rut. His social life consists mainly of eating dinner with his dad. For variety, he sometimes eats dinner at the home of a couple of married friends. Pretty soon the married friends move out.

But that turns out to be OK, because the family that has replaced them is headed by a muscular coach who jump-starts a mayoral “training montage” that depicts AJ working out, changing out of his sweaty clothes, tearing pages off a calendar, and starting over. We think this sequence signifies a passage of time until the coach tells AJ that his workout would do better if he didn’t keep changing clothes and tearing pages off a calendar. Then there’s a cut to a pile of calendar pages and dirty clothes on the floor of the gym. The applause that we heard earlier in the scene was provided by a “CHEERING/APPLAUSE TEAM” that is scheduled to use the room next. The training montage has an EDM score, primary-colored frames, and sweaty shots of AJ, it’s weirdly “hot” in the manner of a ’80s music video.

The movie is jam-packed with sometimes clever, sometimes strained verbal and visual gags. A kidnapped man is pushed into the back of a van, and when we see it from a wider angle, the man is clearly a legless dummy. AJ’s campaign video says that he was “born to a hardworking family that owned 600 acres of farmland” that the young AJ had to tend using 18th century tools. A couple of tiny dogs that figure in the story are later revealed to have gone off to college. When AJ goes to visit them in their dorm, they’re gone. The young man who greets AJ tells him that the dogs just left to go study abroad, and reveals that he is AJ’s godson, who was shown to be an infant maybe two months earlier in the story. There’s a scene in a rowboat with a setup too complicated to explain here that finds A.J. taking a zoom call on a laptop and then having an extended conversation with a fisherman who talks like a pirate and wears a little pirate hat.

There are a lot of non-sequitur choices like those. The Marx brothers would have been able to sell them. “You can leave in a taxi,” Groucho Marx tells Margaret Dumont in “Duck Soup.” ” “If you can’t get a taxi, you can leave in a huff. If that’s too soon, you can leave in a minute and a huff.” But there are no Marx brothers here.

When the pirate tells AJ a story about himself that’s meant to illuminate AJ’s predicament, the movie becomes a barely-animated cartoon, like storyboards with a wee bit of motion added. It’s a very short sequence, but the transformative effect on our perception of the movie is striking. We get a glimpse of what it could have been, had it been animated. Animation is so freeing. You don’t have to worry about a lot of the things that live-action filmmakers feel like they have to worry about. A live-action movie that’s directed like a cartoon can have a similar magical power to unify elements that might otherwise make the project seem erratic and disorganized.

Sometimes the movie seems to admit that it’s not even half-baked. At one point, there’s a cut to AJ reading the story we’ve been watching to kids in a public library. “I feel like we’re gonna need more,” a girl tells him. “It feels like we’re only in act two at this point.” It actually feels like we’re still stuck in act one, but whatever. “Really, you want more?,” A.J. asks. “Don’t you think it’s getting kind of tiresome?” Then he follows up with a promise that does not come true: “There’s a lot more, and it only gets more compelling.” The library joke actually does come around again in a way that earns a laugh, but in general, this is a movie that throws a zillion things at a wall and hopes some of them will not only stick but add up to a vision.

Going any further in elucidating the movie’s problems would be mean, so it’s better to stop here—except to say that there’s a genuinely original sensibility at play beneath all of the missteps, and if it can be excavated and showcased properly, with a specific look, sound and rhythm, the result could be a great nonsense comedy in the vein of older works by comedians like W.C. Fields, the Stooges and the Marxes, and modern masters like Jared Hess (“Napoleon Dynamite”), rather than a collection of gags.