A visit to Mexico, in nine acts.

Act I. The Ride into Town

“You have three things here that make it a great place to shoot a Western,” Jack Casey was explaining. “You have the tall pines, you have the high desert, and you don’t have any jet trails.”

What else is Durango known for? I asked.

“Not a whole hell of a lot else,” he said. “There’s a cotton mill and a mountain made out of iron that I know of. Otherwise, you might say we’re 25 miles from everywhere. Duke put this place on the map.”

The car from the airport passed the largest and most modem structure I was to see in Durango, the penitentiary, and reached the outskirts of town. There were three large concrete sculptures in a little civic plaza. They looked vaguely obscene.

What are those? I asked.

“Those? Those are the three bottles,” Jack said.

The three bottles?

“Yeah, one in honor of every bottling company in town. There’s a Coke bottle, a Pepsi bottle and a bottle of the local soda. You want to get your picture taken in front?”

No, I said, it would be one of those pictures I would always have to be explaining to wise guys.

“We’re here,” Jack said. “Campo Mexico Courts.”

The Campo Mexico Courts was a giant semicircle of semidetached cabins, each one with a carport leaning against it. There was a two-hole miniature golf course, a swing, a slide, and several large slaps of concrete. Each slab honored a Western that had been filmed by a cast staying at the Campo Mexico Courts.

There was a slab for “The War Wagon,” with the handprints, footprints and signatures of John Wayne and Kirk Douglas. There were also slabs and autographs for Glenn Ford, Bruce Cabot, Ben Johnson, James Garner and Rock Hudson.

“Duke put this place on the map,” Jack said. “His first picture in Durango was ‘The Sons of Katie Elder.’ Since then he’s shot so many shows here that his company owns a piece of one of the Western sets outside town.”

What else did he shoot here?

“Well, he shot ‘The Undefeated’ and ‘The War Wagon’ here, and ‘Chisum’ – that was a big one. And ‘Big Jake.’ And ‘The Train Robbers,’ which hasn’t been released yet. And now this one. How many is that? Six? And now two Westerns are being shot here at the same time – Duke’s picture, and Peckinpah’s Billy the Kid thing. It’s gotten to be a regular industry.”

Act II. Peckinpah’s Billy the Kid Thing

“This isn’t just a set,” Gordon Carroll told me. “People really live in this town. There are two or three hundred people who live here between pictures. A company will come in and make a few changes – build a jail or tear down a scaffold – but it’s a real town. You see those pigs running around? Those are real pigs. Those aren’t prop pigs.”

Gordon is the producer of “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” the new Sam Peckinpah Western that is shooting on the other side of Durango from the John Wayne Western.

“We were going to tear down the church,” he said. “But then we decided to tear it half down and leave the scaffolding around it so it looks like it’s half up. Sam and I agreed on that. This way we saved money and got a look of authenticity. Likewise the iron smelting works at the end of the street. We were going to tear that down, but Sam thought it was a good addition to the set. Modern civilization invading the old West and everything.”

So, ah, what’s it like producing a Peckinpah picture?

“We get along real good,” Carroll said. “Sam’s had trouble working with producers before, I’ve heard, but there are always two sides to those stories. I was working on this project for several years, on and off, and when I got it into shape I asked Sam to direct it. Show me a better director of Westerns at work today. And he said, hell yes – he’d always wanted to do Billy the Kid.”

How’d you settle on Kristofferson to play Billy?

“Kris can act. He’s known primarily as a composer and a singer, of course – but did you see ‘Cisco Pike?’ The boy can act.”

Kind of unusual, isn’t it, to have two big composers acting in the same movie – Kristofferson and Bob Dylan?

“I never thought we’d get Dylan. But he’s a friend of Kristofferson’s agent, and so, when we heard Kris was coming on the show, well, then he thought he’d like to. He’s doing it partly to soak up some of the movie business, I think. The fact that Peckinpah is directing had a lot to do with Dylan agreeing to come on the show. He plays a… sort of a kid in town, a printer’s devil, who gets hero worship for Billy and rides out of town to join up with him.”

We stood side-by-side and squinted into the sun while Sam Peckinpah demonstrated to a wrangler the proper method for leading a horse.

“Doesn’t anybody here know how to lead a horse except me?” Peckinpah was saying. “You don’t pull the son of a bitch, you lead it. Hold the reins up here, like this.”

The wrangler, a middle-aged cowboy who had been cured to the consistency of fine old leather by a lifetime in the sun, watched attentively and nodded as Peckinpah ran through the demonstration again.

Well, I said, with Dylan and Kristofferson both on the picture, you’re not going to have any problems with the score, I guess.

“I dunno,” said Gordon Carroll. “Kristofferson is here primarily as an actor. Dylan too, of course – but if they want to write some music of course that would be out of sight. Bobby’s written a couple of things. I don’t know who he’s let hear them yet…”

Act III. Getting a Feeling for the Place

I stood on the porch of the livery stable, trying to maintain a low profile. My strategy was to avoid usual big-star interviews and just observe a movie company in action on a real location. When a big Western goes on location, it’s like a little settlement; not only do the stars have nicknames, but so do the seamstresses, the prop men and the electricians. I’d done so many routine interviews with stars in the past that I thought I’d just soak up the atmosphere this time – try to get a feeling for the place. Little did I know how easy this would be on the Peckinpah picture.

“Bob Dylan is strictly off limits,” the press agent told me. “No interviews, no pictures. He’s appearing in the picture in order to become familiar with the movie-making process. Peckinpah, he doesn’t like to give interviews, either. Maybe you’ll get into a conversation with him or something.

“Kristofferson, he’s OK. He’s friendly, and he’ll talk, but he spends a lot of time with Rita Coolidge, his girlfriend. He doesn’t like to be interrupted during personal moments. Try not to get him in a personal moment. Jim Coburn is very co-operative. He’ll talk, but he doesn’t like to sit down and go through the whole interview bit unless he has to.”

I took all this in and stepped back further into the shade of the livery stable porch. Peckinpah was surrounded by four dozen people and two cameras. How was I maybe going to get into a conversation with him or something? Kristofferson? I didn’t even see Rita Coolidge.

“Visiting the set?” a cowboy asked me.

Uh-huh.

“Newspaperman,” he stated, nodding at my pencil and paper.

Yeah.

“Funny thing. I was a stunt man on a picture here a few years ago, and the day they picked to bring the press out, I was doubling some scenes for the star and the star wasn’t there so they all interviewed me.”

Oh yeah?

“Yeah. Nothing ever come of it, though. My name’s Walter Scott.”

I shook hands with Walter Scott, who had to leave in order to have a wig and mustache attached to his head. His next assignment for the afternoon was to double for a dead man. I looked around and found myself being nodded at in a friendly fashion by another cowboy. I asked him if he were a stunt man, too.

“Nope. Wrangler.”

I nodded and asked him how Bob Dylan was getting along on the picture.

“Can’t say! Haven’t met him. They say he’s a very private individual. Rented a house for his wife and kids, and his dog.”

How many kids does he have?

“Can’t say. Dog’s name is Rover.”

Act IV. Billy’s Big Scene

“Being a stunt man is a very exacting science,” James Coburn explained to me. He took a draw on his French cigarette, one of those Gauloise that can cause a permanent squint. “It looks easy, falling off a horse,” he said, “but it’s a science. It involves falling off a horse at a specific time and in a specific place and in a certain way, and not getting your ass broke. There’s an art to it.”

We were watching while Peckinpah set up the afternoon’s big scene. The scene comes just after Billy the Kid, played by Kris Kristofferson, has shot his way out of jail. He has bribed an old man to bring him a getaway horse. While the townspeople watch in shock, the old man brings Billy the horse and he gets on it. What Billy doesn’t know is that the horse is a bucking horse.

“I think I can ride her myself, Sam,” Kristofferson told Peckinpah.

“Think so, eh?” said Peckinpah, slouched in his canvas director’s chair. “Whatever made you think you could ride a horse?”

“I’m a good rider, Sam,” Kristofferson said. “Use me and you won’t have to double.”

“Try it with him once,” Peckinpah said.

Kristofferson went inside the jail, Peckinpah’s assistant director shouted, “Quiet! Rehearsal!” and Kristofferson came stomping out. The townspeople shrank back on cue. The old man brought Kristofferson the horse. He tried to mount it, but the horse shred away. Kristofferson held it steady, mounted, and began to ride down the street. Something frightened the horse and it began to dance sideways. Kristofferson quieted it and looked back at Peckinpah.

“No,” Peckinpah said. “No, it’s too big a risk. That’s a mean horse. It’s too big a chance to take. Kris, you mount the double horse and then we’ll use the double for the bucking horse.”

“That means me,” Gary Combs said. He was a stunt rider, lean and muscular, dressed in a costume and wig to make him look like Kristofferson from behind. “What do you need, Sam?”

“Just spin him, flank him and hit the dust. He’ll buck the minute you start to flank him.”

Peckinpah filmed Kristofferson’s exit from the jail and got him mounting the horse. Then it was time to switch to Gary Combs and the bucking horse.

“Here goes,” said Walter Scott, the stunt man. He inspected the blood on his costume and pounded some dust out of his hat.

What do you have to do? I asked.

“Lay down dead for the bucking horse to maybe run over me,” he said.

What if he does?

“Why, God damn it, I’m in real trouble.”

Walter walked to his position and lay down, dead. Peckinpah called for a shot. The assistant director bellowed for quiet, for background action, and for action. “Both cameras,” Peckinpah said. “Right, Sam,” his assistant said.

Gary Combs, shot from behind, spun the horse and rode him down the street. Opposite the church, he flanked the horse and it began to buck, viciously. He held on for what seemed like an impossible number of seconds and then he was thrown loose. He flew in a sharp arc through the air and landed on his face, hard. He did not move.

“Cut,” Peckinpah said.

Combs still didn’t move. There was a moment that seemed like an eternity, with everyone in the set looking at the body flat in the dust.

“Christ,” Peckinpah said softly, “the son of a bitch has killed himself.”

And then everybody was running toward the body, and strange white 20th Century hallucinations appeared from behind the walls of the old Western town. A doctor ran forward with his medical bag. An ambulance backed out from behind the jail. Walter Scott ran across the street to his friend, and was the first at his side. The doctor slipped an oxygen mask over Comb’s face, and there was a deathly stillness.

Combs finally blinked, and coughed, and sat up, shaken and disoriented.

“Did you get it?” he asked Peckinpah.

“Looked good,” Peckinpah said. “How do you feel?”

“Ooooof,” Gary Combs said, shaking his head.

When be saw that the stunt man was indeed still alive, James Coburn walked back to his chair behind the camera.

“It’s an art and a science,” he said. “And then when a stunt man takes a real fall and damn near kills himself, they say it looks ‘too good’.”

He lit another cigarette. I’d interviewed him last spring in Seattle, when he was shooting a movie about pickpockets, and asked him how it turned out.

“I don’t know. I haven’t seen it yet. Since then I shot a movie on an island off the Riviera. Something called ‘The Last of Sheila.’”

Wasn’t that the movie, I said, where Raquel Welch claimed everybody hated her?

“Hell, nobody hated her,” Coburn said. “We just didn’t notice her enough. For her, Raquel Welch is all that exists.”

Prop men were busy with their brooms, scattering the dust where Gary Combs had fallen and everybody had made footprints standing around him. Peckinpah settled down in his director’s chair again. Walter Scott brought Gary a cup of lemonade, and Gary drank it down. Life ended, and art resumed.

Act V. An Interlude for Ducks

Back at the Campo Mexico Courts that evening, I was taking a drink of the bottled water in my room when I heard a duck next door. I walked to the door, saw no duck, and stepped out onto the porch. At that very moment, Dub Taylor stepped out onto the porch next door.

Dub Taylor is an actor whose name you may not remember, but you have seen him in a dozen movies. He is one of the busiest character actors in the world, and played C. W. Moss’ father in “Bonnie and Clyde.” He looked at me and quacked.

“Hell, I can do it with a call or without one,” he said. He pulled a duck call from his pocket, hung it around his neck on a leather strap, and quacked some more.

“My pappy taught me,” Dub said. “There’s different calls for different times. You want them to land, you gotta tell them to land. You got to get your vocabulary straight. Ducks is smarter’n some people.”

He came over and sat on my porch.

“Yes,” he said, “been married for years. That’s my son you see on ‘Gunsmoke.’ I been in the business more than 35 years. Frank Capra gave me my start in pictures. Before that, I was an entertainer. Vaudeville. I played the xylophone, and the harmonica some.”

And now you’re one of the two or three most famous character actors in the world, I said.

“Hell, this here’s a regular character actors’ convention,” he said. “Between the John Wayne movie and the Sam Peckinpah movie, every character actor in the world is staying at the Campo Mexico Courts right now.” Dub is appearing in “Billy the Kid.”

As if to prove him right, Jack Elam walked past, wearing a ferocious beard.

“Jack,” Dub said.

“Dub,” Jack said.

“We see each other all the time,” Dub said. “There’s always work for a character actor. Lessee who we got down here right now. We got Slim Pickens – you ever see him in a movie? He’s been in a thousand. We got Harry Carey, Jr., and L.Q. Jones, and Jackie Coogan. Marie Windsor is down here. Denver Pyle. Royal Dano. Neville Brand, Pepper Martin. Strother Martin was supposed to be down here, but he couldn’t make it – they even named his character for him just like they named Denver’s character Denver.”

He paused for a quack or two.

“The secret is,” he said, “that I am 90 percent pig crap. Only 10 percent intelligent. Ninety percent of the people is 90 percent pig crap, and so when they see me, they recognize themselves.”

He nodded as if that settled it.

You must make a lot of money as a character actor, working all the time, I said.

“Hell, no. I got in hock to Seaboard Finance 20 years ago, and in all that time I never been able to get out from under. They know me by the sound of my voice now. I never sign nothing – I tell ‘em I can’t read, can’t write. Just call up and say, Seaboard, this is Dub again.”

Act VI. Dinner at the Campo Mexico Courts

Ralph said he was John Wayne’s trainer.

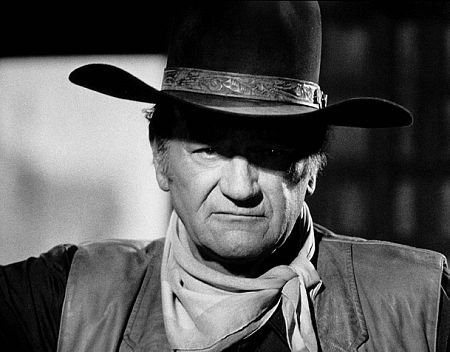

“Not his masseur – his trainer,” he explained. “I’ve worked for a lot of boxers who were as big as boxers as Duke is as an actor. I’ve been with the Duke 18 years, 19 years in January. I figure I came in with him and I’ll go out with him. He’s got a couple of years to go. The thing is, he looks younger today than he did 10 years ago.

“Whenever he makes a movie, I’m there,” Ralph said. “The rest of the time, he forgets me, I never hear from him. But when he’s shooting, I’m there. I’m on call 24 hours a day. He might get a cramp, a Charley horse. I’m there. I know if I ever needed money, if I needed help, say I was sick or something, he’d be right there, too.

“What worries me is, he’s smoking again. He says it’s only cigars, but it’s these little cigars. I’ve told him, and other people have told him. One thing about the Duke: You can’t tell him something twice. Still, he’s in great shape. For this picture, we’ve got him down at 237 pounds, which is the least he’s weighed in a long time. He looks great.”

Act VII. The Warehouse

“Cahill U. S. Marshal,” Wayne’s new picture, was being directed by Andrew V. McLaglen, the only director in Hollywood as tall as John Wayne, although Howard Hawks came close. It was shooting the next day in an old cotton warehouse next to the railroad tracks in Durango. The warehouse wasn’t soundproofed, so everything had to stop when a train went past.

Inside the warehouse, the prop men had constructed an outdoor clearing. The floor was covered with damp dirt and sawdust, and everyone was coughing and sneezing. It sounded like three in the morning on a bad night in the TB ward.

“There’s no question about it, it’s a dilemma,” John Wayne said. “It’s a question of wetting down the dirt and freezing our ass all morning, or not wetting down the dirt and fighting the dust all afternoon.”

He took a paper cup of hot chili soup from a tray and drank it down.

“Haven’t you got that horse steadied yet?” he said.

Two wranglers were trying to position a horse in the clearing. The shot called for the horse to he facing west, and the horse wasn’t having any. The horse wanted to face east.

The scene they were preparing to film was a basic one. John Wayne and Neville Brand, who plays a Comanche war chief, are riding on the same horse when they’re swept off by a rope strung across the clearing by treacherous enemies. Brand breaks his leg, and Wayne sets it.

“Christ,” Wayne said, “isn’t there anyone on this set who can handle a horse? We might as well just move the camera and shoot the way the damn horse wants us to.”

The wranglers tugged and pulled, and the horse braced its legs like a mule.

“Get one of those fellows on the horse’s head and the other fellow on the other end,” Wayne said. “Have them push at the same time.”

Andrew V. McLaglen, the director, nodded morosely. He was wearing a surgical facemask – whether to avoid catching cold, or to avoid spreading a cold of his own, it was difficult to say. The wranglers pushed and pulled, and the horse came around. Wayne, doing most of his own direction in this scene, ran through his lines with Neville Brand. In the event you have not seen a John Wayne movie in the past 30 years, they may sound unfamiliar:

WAYNE (picking himself up off ground): “Holy Christmas!”

BRAND (sprawled against tree): “Like takin’ candy from a baby, huh? Ha, ha, ha”

WAYNE: “Very funny.”

BRAND: “I’ll tell ya somethin’ else that’s funny. My leg’s broke.”

WAYNE: “Let’s see.”

He kicks Brand’s leg.

BRAND: “Aaaaaaiiiiiiieeeeeee!”

WAYNE: “Well, I guess you’re right.” (He kneels down beside Brand.) “I’ll have to straighten and splint it.” (He pulls a cigar from his pocket.) “Here’s somethin’ to bite down on. This is gonna hurt.”

BRAND: “Thanks. I… Aaaaaaaiiiiiiieeeeeee!”

WAYNE: “I thought Injuns didn’t show pain… ‘Specially Comanche war chiefs!”

Wayne and Brand ran through this dialog a couple of times, getting it more or less right but not quite exactly right, and Wayne finally called for silence: “What does a guy have to do to get a little damn quiet around here? This scene isn’t easy.”

Silence. Wayne and Brand got it right. Wayne walked over to his chair – with “Duke” stenciled across the back – to talk to an interviewer from the London Sunday Express.

“Would you say you are a conservative?” the Englishman asked him.

“Hell,” Wayne said, “I always thought I was a liberal. Listening to both sides before you make up your mind doesn’t that make you a liberal? Not in the terms of today, it doesn’t. These days, you have to be a fucking left-wing radical to be a liberal.”

“I see,” said the man from London.

“My favorite man was Taft,” Wayne said.

“Yes, yes,” the man from London said. Very good President, wasn’t he? Yes.”

“Not that Taft, you dumb asshole,” Wayne said. “Robert Taft.”

“Yes, yes, I see,” the reporter said.

“All the things the liberals were for, he was for, but in a quiet way,” Wayne said. “And he didn’t only tell people their rights, he told them their responsibilities.”

“Of course.”

“But I guess you’re right,” Wayne said. “Politically, I have mellowed. I don’t give a good god damn.”

Outside the cotton warehouse, a dog began to bark. “Somebody quiet that dog,” Wayne said. “BANG! Thank you.”

Laughter.

“It’s funnier with a baby,” Wayne said, smiling. “Wasn’t that Fields who did that? Quiet that baby! BANG! Thank you.”

“Very funny,” the man from London said.

“Belittling our President, that’s what they’re doing,” Wayne said. “He’s a man with power, and the decency to use that power fairly. When he mined Haiphong harbor, all the cute boys, the Severeids and the Cronkites and those other a——-, said that would end the Russian trip. Well, they were wrong. The Russians know who’s boss.”

“Yes, of course,” the London reporter said.

“Nixon acted with honor,” Wayne said.

“Yes, yes.”

“You know the only thing that’s better than honor?” Wayne said.

“No, what’s that?”

“Inher.”

Act VIII. Wayne vs. Ebert (Durango, 1972)

“You play chess?” John Wayne said.

“Yes, I do,” I said.

“Those Russians were through Chicago, weren’t they?” he said.

A couple of weeks ago, I said.

“They pretty good?”

That’s what I read.

“They’re just about the best. Except for Fischer, they are. Christ, that fellow can play chess!”

What’d you think about his tactics?

“He won, didn’t he? In chess, that’s all that counts. It’s not a game of luck, it’s a game of logic. Fischer had the better logic.”

We left the big warehouse and walked to Wayne’s trailer, which was parked outside. He pulled down his battered old chessboard and set up the pieces. Chess has been John Wayne’s game for more than 40 years. He may be a friend of the vice president, but when was the last time you saw a photograph of Wayne playing golf with Agnew? Golf isn’t Wayne’s game, and Agnew’s is manifestly not chess.

The Duke drew white and opened with his queen’s pawn. I tried the Nimzo-Indian defense and the game moved along fairly conventional lines, or so I thought until we arrived at the middle game and Duke was a bishop and a knight up on me. Wayne’s photographer, David Sutton, sat on the edge of a couch and kibitzed. Wayne smoked small cigars and said nothing.

Well, how would you have felt, playing chess with John Wayne? The first time I ever saw him in person, he was directing “The Green Berets” at an Air Force base down in Georgia, and he looked so intimidating and authoritative in uniform, with his battle helmet on, that I could hardly think of a thing to say and was barely able to prevent myself from saluting.

I’ve interviewed him a couple of times since then, but the feeling has never quite gone away… the feeling that John Wayne is in some measure larger than the rest of us. There is something in his bearing and manner, and something in our memories of the dozens of Saturday afternoon matinees we spent in his shadow, that will always impart this quality about John Wayne to the people who grew up and went to the movies in the 1940s and 1950s.

Sitting across the chessboard from him, I felt, perhaps, something like poor Spassky must have felt. I knew I was a fairly decent chess player, as strong as Wayne, anyway; and Spassky knew that he was the world champion, and Fischer just a callow boy from Brooklyn. Still, there was something… some… aura, some ultimate confidence, that…

As it happened, Wayne grew overconfident and absentmindedly allowed me to pin his rook and knight. I took the rook, and maneuvered into a situation where I had mating chances. We exchanged moves, and then I sat looking at the board and realizing that all I had to do was move my queen and he would be mated.

“God… damn!” Wayne said.

I mated him.

“God damn!” he said. “If I hadn’t said ‘God damn,’ you wouldn’t have seen it!”

“Well…” I said.

“You was robbed, Duke,” said the photographer.

“God damn,” Wayne said, staring at the board.

Act IX. Half Past High Noon

Back in the cotton warehouse, shooting began on the scene in the clearing. Wayne handed Neville Brand the cigar, Brand bit down, and Wayne rotated the broken leg.

“Aaaaaaiiiiiieeeeee!”

“Good. Cut.” McLaglen, the director said. “Let’s get one more.”

“He’s a natural,” the British journalist told me.

Yep, I said.

“He’s made so many Westerns, he acts by instinct, without thinking.”

Well, I said, if anybody knows how to make a Western, John Wayne does. “Look at this,” the British journalist said, as Wayne stooped down to twist Neville Brand’s leg again. “Watch. He stoops down, he says his lines, and without even thinking he just instinctively knows not to goose himself with his spurs.”

“What was the greatest Western ever made, Duke?” the British journalist asked.

“Hell, I dunno,” Wayne said. “Whatever it was, it was probably directed by Jack Ford.”

“What’d you think about ‘High Noon’?” asked the man from London.

Wayne looked pained. “What a piece of you-know-what that was,” he said. “I think it was popular because of the music. Think about it this way. Here’s a town full of people who have ridden in covered wagons all the way across the plains, fightin’ off Indians and drought and wild animals in order to settle down and make themselves a homestead. And then when three no-good bad guys walk into town and the marshal asks for a little help, everybody in town gets shy.”

John Wayne studied the end of his cigar.

“You know what I would have done, if I’d been the marshal?” he said at last.

“No, what?”

“I would have been so god-damned disgusted with those chicken-livered yellow sons of bitches that I would have just taken my wife and saddled up and rode out of there.”