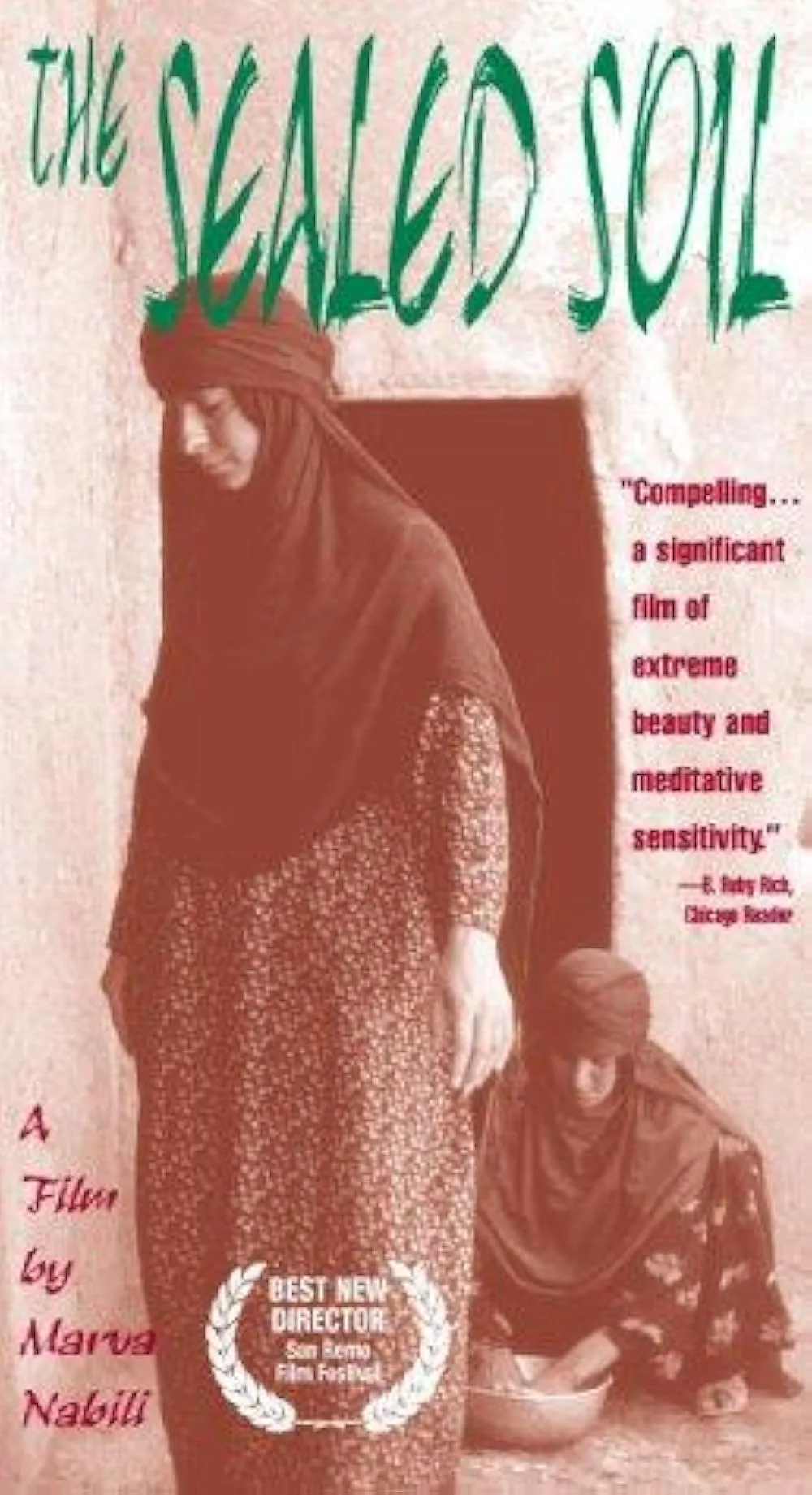

Marva Nabili’s 1977 feature “The Sealed Soil” is the earliest intact surviving feature film directed by an Iranian woman. It has been nearly impossible to see for decades. Its restoration and release by the UCLA Film and Television Archive would be cause for celebration even if it were of purely historical interest. But it’s more than that. It’s a great, though admittedly demanding, movie that draws us into a character’s mindset simply by showing us what their life is like.

Made as a graduate thesis film on a tiny budget, and ably acted by a cast of nonprofessionals, this story of a young woman from a small village whose life is constrained by Iran’s specific type of patriarchy is one of the most assured first films you’ll ever see. It makes its points subtly, at times invisibly, letting details of a very specific time and place sink in gradually, building pressure until there’s an explosive release. I was not prepared for how focused and slow-moving the first section would be, nor was I prepared for how powerfully the rest of the story would hit. A movie so committed deserves a similar level of commitment from its prospective audience, and hopefully, “The Sealed Soil” will receive it.

The protagonist, 18-year-old Rooy-Bekheir (Flora Shabavis), is an example of what would be rudely called “a spinster” in Western countries several decades ago. She’s “marriageable” and still very young, but she hasn’t gotten married yet. She just isn’t interested, even though her life of obedient service to her father, mother, and siblings is a grind that she knows better than to complain about. The movie is set in contemporary times, under the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, who became the ruler of Iran in 1941 and, as of the movie’s release, had another three years left in office before Islamic fundamentalists took over. His regime had set Iran on a gradual course to become more Westernized, with privileges that included more freedom for women, which our heroine has exercised in her way by not getting married.

But as we can see, “freedom” is a relative term. In this case, it means “things could be worse.” Rooy-Bekheir is depressed. You can see it in how she walks and talks, stays placid and silent when receiving bad news, and sits quietly at a family dinner until her mother makes her feel self-conscious for not eating. There’s a spot by the river where she goes each day to fetch branches for the family. Sometimes she spends more time there than she needs to, because she enjoys the solitude and lack of responsibility. (We can infer this last part from the filmmaking and acting rather than being stated outright in dialogue or voice-over. This is typical of the movie’s austere, “show, don’t tell” aesthetic.)

Something like a story manifests itself when the mayor of the village lets it be known that the local agriculture corporation that currently owns the land intends to displace them, and is offering a set amount of money in exchange for households choosing to move on their own terms. The family is struggling and needs money, so this option is not only on the table, it’s probably inevitable.

But there’s another way the family can make a chunk of money fast: by convincing Rooy-Bekheir to enter into a marriage agreement, for which the parents will receive a dowry in exchange. The initial offer includes 500 Tomans, a television for the family, and three pieces of fabric, including three shawls and two pairs of shoes, for the prospective bride. The dialogue is careful to show us that, although the heroine has options, she doesn’t have many, and that the traditional restrictive practices haven’t been defanged by the current government so much as sanded and smoothed.

One of the many quietly powerful scenes finds the mayor visiting the household a second time to pressure Rooy-Bekheir to get married. Look at how he frames the issue: as a decision that she has every right to make for herself, but that would give more happiness to more people if she would just do what’s typical of a woman in her position. “Listen,” he tells her, “at seven, your mother married your father. At your age, she’d already borne four children. Four! I remember she was a teen. She used to run away once a month from your father, and my dad would send her back. Today, you can’t force a girl to marry the man. Today, the girl decides.” That’s one of the worst sales pitches of all time. After the mayor leaves, everyone else follows, leaving Rooy-Bekheir alone to roll up the throw rug and put it away, just as she always has to do.

“The Sealed Soil” is a perfect example of what is now labeled “Slow Cinema,” a term that didn’t exist when this movie first came out, and wouldn’t for another thirty-plus years. As such, viewers accustomed to a more commercial, plot-driven, and heavily edited style will need some time to get immersed in its groove, provided they don’t abandon it immediately for asking too much of them. The first half-hour is deliberately uneventful and repetitious, to fully immerse us in the life of a character who lives a mostly uneventful and repetitious life.

But there’s a point deeper into the movie where we see her walking alone on a road. The music swells and, if you’ve committed to any degree, suddenly you’re locked in. The entire thing becomes hypnotically compelling, as if we’re witnessing a mythic epic about a woman’s will being tested, which is precisely what we’re seeing, even though it’s presented in an outwardly mundane manner. The movie has the proper ending, which isn’t necessarily the most satisfying one. You come away feeling that you’ve been told nothing but the truth, which is a rare sensation in any art form, let alone narrative filmmaking.