Perhaps they really did think they’d heard the last of Sheila. She was a gossip columnist who left a party early one morning (a little loaded, probably) and was walking down a street in Bel Air when she was killed by a hit-and-run motorist. But that was a year ago. So when her husband invites them all over to France for a week on his yacht, it sounds like fun, not a wake.

There’s one little catch, though. It turns out that one of the cruise guests is the hit-and-run murderer. Sheila’s husband (James Coburn) knows who. But he isn’t after mere legal solutions. He wants sadistic revenge. So he plans a game, a very complicated game. He hands all of the guests typewritten cards with secrets on them. Not their own secrets; somebody else’s secrets. One of the guests is an alcoholic, one is a child molester, one was an informer during the witch-hunts. And so on. Every night there will be a hunt for clues onshore. Gradually everyone’s secret will be discovered. And Saturday night is set aside for the murderer.

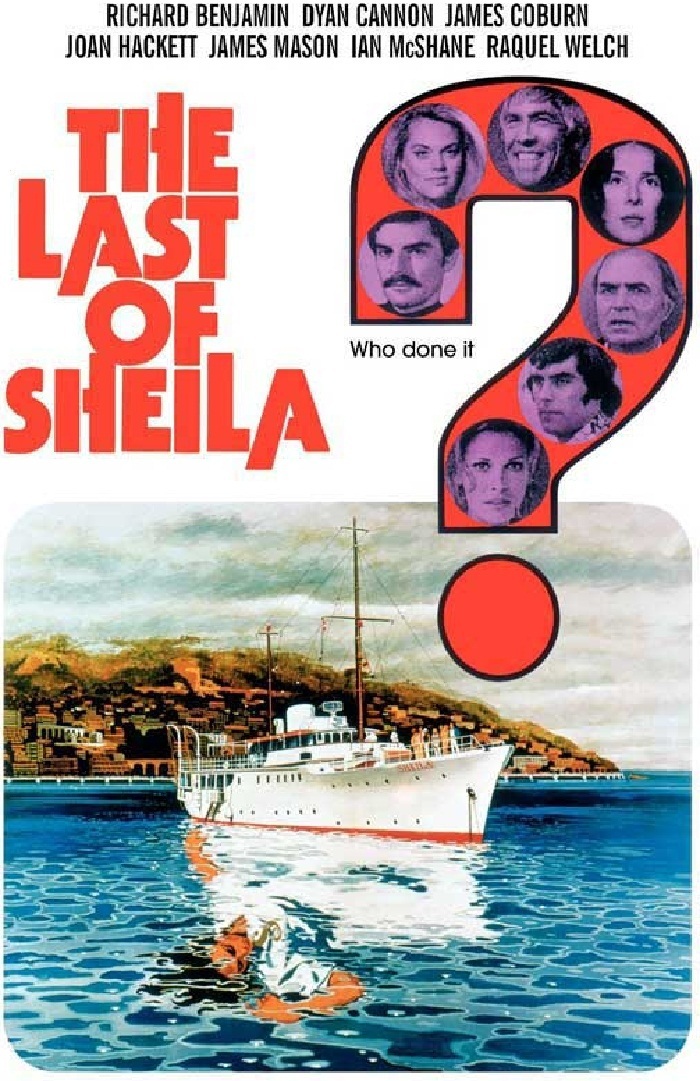

That’s the premise of “The Last of Sheila,” which is a devilishly complicated thriller of superior class. It involves game playing in the way “Sleuth” did, but the game is more devious. And the movie itself comes out of a grand tradition of murder puzzles from such as Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr. Indeed, it’s a little unexpected to see this material showing up first as a movie; it seems like the kind of story that would begin life as a play. Bringing seven people together and then doing the old “one of the people in this room is a murderer” routine is innately theatrical, as the 20-year London run of Miss Christie’s “The Mousetrap” illustrates. Still, it works well as a movie, maybe because the screenplay is concerned as much with characters as with crime. The movie was written by Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins, and they exhibit a very fine eye for showbiz behavior and dialog. They’ve also played a sort of Jacqueline Susann guessing game for us; we can have fun wondering who the bitchy agent (Dyan Cannon) was inspired by, or the down-at-his luck director (James Mason), or the sexpot (Raquel Welch, who may very well have been inspired by herself).

And it’s fun to listen to their conversations, which, like the talks In “Play It as It Lays,” sound like dialog because these people talk no other way. The in-jokes are good, too, and the movie is especially accurate in its assessment of the Hollywood attitude toward death. Hollywood is embarrassed by death and turns away from it; real grief is seldom. One is reminded of Frank Sinatra’s remark at Harry Cohn’s funeral: “I only came to make sure the son-of-a-bitch is dead.” The movie begins as a cat-and-mouse game involving Coburn and the killer. But it takes a stunning turn halfway through, when Coburn himself is murdered and the guests themselves have to finish the game. And it really is a game to them; they don’t spend time grieving when somebody dies, but simply clean up the blood and chalk up one more loser against their hopes of a win.

The performances are sharp-edged and mean, and very good, especially Dyan Cannon as the agent. Joan Hackett is lovely and soft as perhaps the group’s only honest member, and James Mason displays his usual civilized stubbornness as the guest who finally solves the mystery. It’s the kind of movie that wraps you up in itself, and absorbs you at the very time you’re being impressed by its cleverness. And it leaves you thinking maybe Sheila got off easy, after all.