Film noir: A motion picture with an often grim urban setting, photographed in somber tones and permeated by a feeling of disillusionment, pessimism and despair.

— Random House Dictionary

And, they might have added, you can’t really get inside a film noir unless you are a romantic — a person who sees life in terms of the grand gesture and fate as a pair of dice.

After I saw “Johnny Handsome,” I was unfortunate enough to encounter a couple of pragmatic, modern, nonromantic types who assumed without even asking me that I had not approved of the movie. They were bright young things who found the movie filled with “stereotypes.” I wish the professors who teach about stereotypes in undergraduate lit classes would remember to add that they are not necessarily a bad thing – that sometimes a film is better because it returns to its roots.

“Johnny Handsome” comes out of the film noir atmosphere of the 1940s, out of movies with dark streets and bitter laughter, with characters who live in cold-water flats and treat saloons as their living rooms. It is set in New Orleans, a city with a film noir soul, and it stars Mickey Rourke as a weary loser who has just about given up on himself.

They call him “Johnny Handsome” because his face has been horribly disfigured since birth, and as the movie opens he and his best friend have been double-crossed by a couple of crooks who kill the friend, steal the loot and leave Johnny to take the rap.

In jail, he’s offered a deal if he’ll identify his accomplices. He refuses, because it is the underworld code that you do not rat on your associates, and also because he plans to kill them when he gets back on the street. But then an interesting thing happens to him: In jail, a thoughtful surgeon (Forest Whitaker) suggests that plastic surgery could turn Johnny into a reasonably average-looking guy, and speech therapy could make him into a passable candidate for rehabilitation.

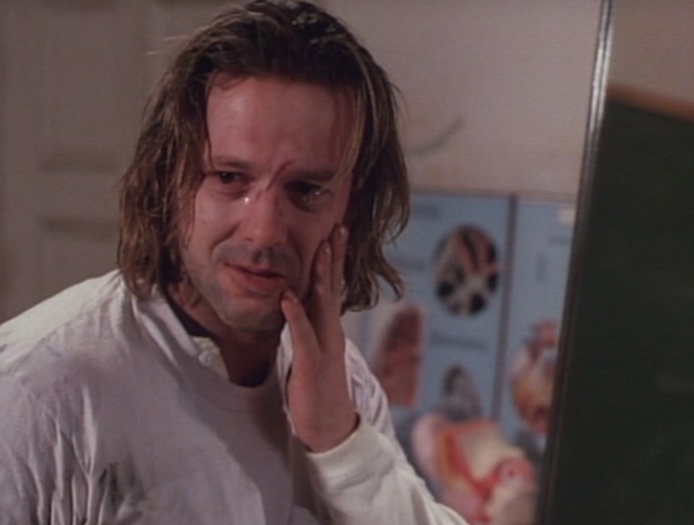

Johnny has nothing to lose, and undergoes the surgery (which, true to the tradition of movies like this, is a snap). Out on parole, he goes straight with a job down on the docks. And he meets a girl (Elizabeth McGovern) who loves him. But Johnny has a problem: He has spent so many years walking around feeling distrustful and grotesque and unlovable that he has a hard time handling success. The movie presents him with a clear choice: He can go straight, keep his nose clean and be happy with this woman. Or he can return to crime and carry out his revenge.

Because we live in a time of simple-minded action pictures — with audiences that are less adventurous than those of the 1940s and stars who like to look good at the end — there is the assumption that Johnny will take the direction of growth and happiness (not without some setbacks, of course). But Walter Hill, who directed this film, and Rourke, who seems to seek out difficult projects, would not have been interested in a simple approach. This is dark material, and they head for the shadows.

The movie is filmed with real style. Matthew F. Leonetti, the cinematographer, finds a gritty loneliness in the seedy quarters of New Orleans, and the Ry Cooder music is a cross between the blues and a sob.

The movie benefits from strong supporting performances by an unusually distinguished cast (including Ellen Barkin as one of the double-crossers and Morgan Freeman as a cop who can’t wait for Johnny to fail). And Hill (who made “48 HRS.” and “Streets of Fire“) directs with an almost rude disregard for modern Hollywood convention.

This is a movie in the true tradition of film noir — which someone who didn’t write a dictionary once described as a movie where an ordinary guy indulges the weak side of his character, and hell opens up beneath his feet.