Grave and somber, Scott Cooper’s “Hostiles” opens with a scene that recalls John Ford’s “The Searchers.” In 1892 New Mexico, a family of homesteaders—mom, dad, three kids—are going about their business when Comanche warriors thunder toward their ranch. Grabbing a rifle to defend his family, the father is cut down and scalped first. Before setting fire to the ranch, the Natives go after the rest of the family and kill all the kids. Only the mother survives by hiding in the woods.

The nod to “The Searchers” is a bit misleading, though. Unlike this month’s other neo-western, Jared Moshe’s terrific “The Ballad of Lefty Brown,” which harkens back to classic westerns by directors like Ford and Howard Hawks, Cooper’s film belongs more to a lineage that includes “revisionist” westerns such as Robert Aldrich’s “Ulzana’s Raid.” By any reckoning, it is one of the most vivid and compelling evocations of the bitter, violent hatreds that once separated Native Americans from the settlers and soldiers who invaded their territories.

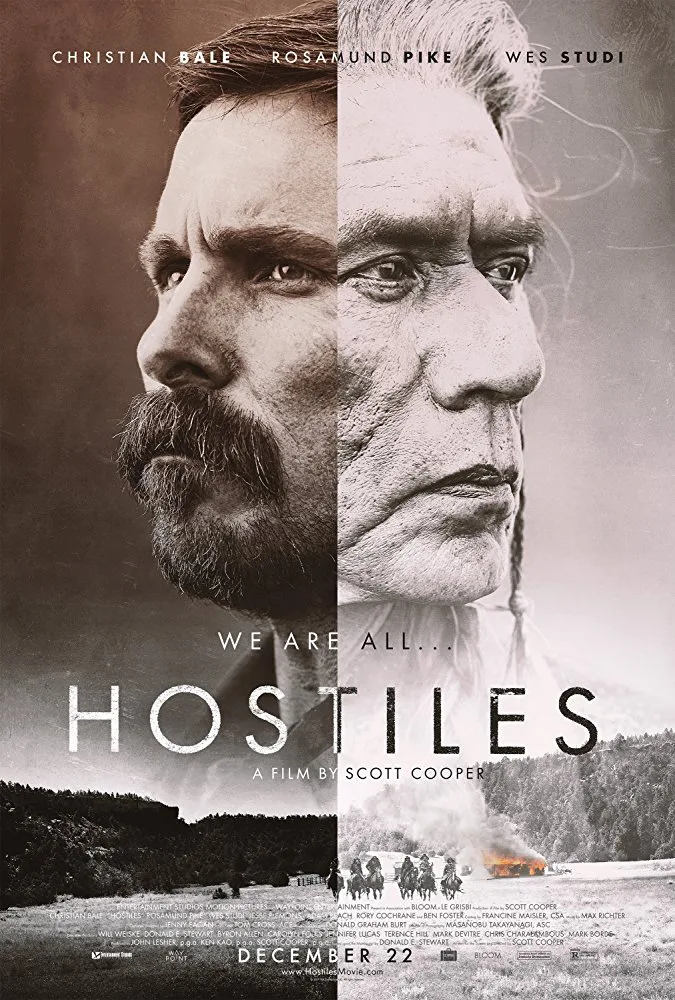

The film has a lot going for it. Besides the gorgeous, burnished look supplied by cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi, Cooper gets a range of fine performances from a topnotch cast that includes Christian Bale, Rosamund Pike, Wes Studi, Ben Foster, Scott Wilson, Q’orianka Kilcher and Timothee Chalamet. Its main fault lies in the department where so many ambitious, handsomely mounted films falter: story.

Scripted by Cooper “from a manuscript by Donald E. Stewart,” the tale begins in earnest when it shifts from that initial massacre to a cavalry fort where Captain Joseph Blocker (Bale) is given the last assignment he would ever want. For seven years the fort has served as a prison for aging, ailing Cheyenne chief Yellow Hawk (Studi) but now, as Native resistance to white domination is all but finished, a new mood of progressivist clemency in Washington has decreed that the chief can return to his tribal home in Montana to die. Told to escort Yellow Hawk and his family on the long journey, Blocker is so opposed to the order that he at first seems willing to be court martialed rather than accept it.

The reason is simple: he deeply, passionately hates Indians, having fought them frequently and been the target of their violence. One reason the story gets off to a strong start is Christian Bale’s effectiveness in conveying this character’s bitterness and anger. Though his mouth is largely covered by a droopy handlebar moustache, Bale’s fierce eyes radiate looks that are at once haunted and haunting, reflecting years of pain and rage.

Once on the trail, Blocker demeans the dignified chief by keeping him in chains. But his unwelcome assignment is complicated further when the party arrives at the ranch where they discover the massacre and the surviving wife, Rosalee Quaid (Pike). She is traumatized, and the task of burying her family puts everyone in a grim mood. Nor is the mood improved when it becomes apparent that the marauding Comanches are still on the warpath. Fighting them, and trying to make it through their territory alive, is the effort that occupies Blocker’s party for most of the story’s first half.

Thereafter, they arrive at a fort where it is determined that Mrs. Quaid will continue on with Blocker and his men, who now find a new assignment added to their original one: They’re supposed to take a soldier accused of murder (Foster) to a town where he will be tried. It is at this juncture that the tale begins to lose its focus. Are we concerned with the horrible relations between Natives and other Americans, or with the animosities among soldiers? Though Blocker and the prisoner have a back story that touches on their anger over Indian fighting, this whole section of the narrative seems superfluous and digressive.

As becomes evident early on, the real, inward journey depicted in the film is the one where Blocker recovers his humanity by learning to grant the Indians theirs. This is a worthy theme and dramatic premise but it’s only partly, and rather unsatisfactorily, realized. While Blocker’s gradual change of heart—which eventually includes the first flickers of romantic interest in Mrs. Quaid—comes across thanks to Bale’s strong performance, the film’s biggest flaw lies in how underwritten the Indian parts are. Though the venerable Wes Studi is a commanding presence and fine actor, his character is given very little shading or dimension, and the other Indians are allowed practically none.

This adds up to a film that’s beautifully shot and acted, but also meandering, overlong and only sporadically focused on its central issues. As for its politics, in making the story primarily about one (white) man’s redemption, “Hostiles” falls back on a well-worn if still potent dramatic trope while saying virtually nothing about the genocide committed against Native Americans.