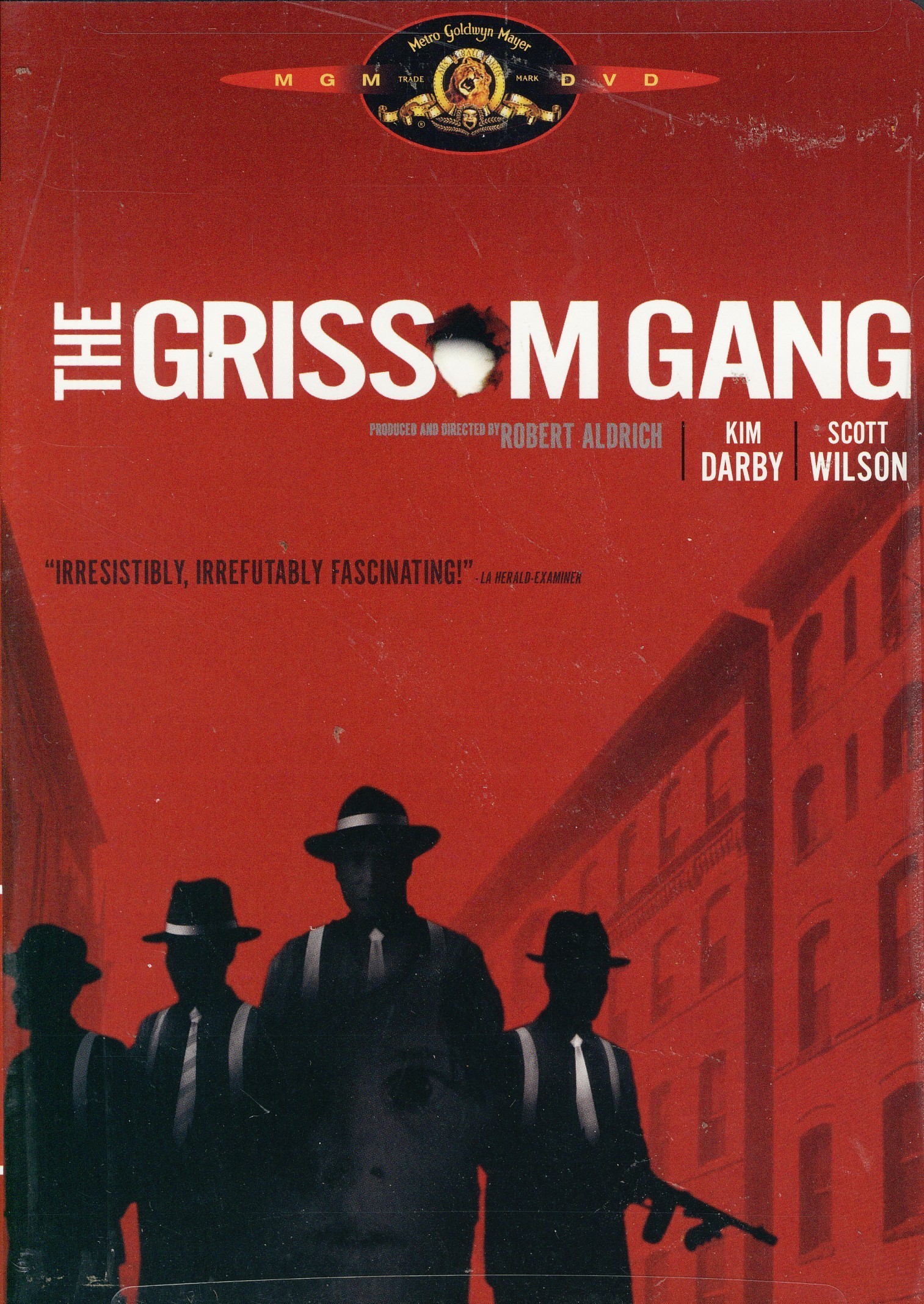

Robert Aldrich’s “The Grissom Gang” is buried deep within that late-1920s, early-1930s atmosphere that’s suddenly become so familiar in American movies. The film opens with a black screen and the scratchy, far-off voice of Rudy Vallee singing “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby,” and then Aldrich fades in to show us a dusty backroads gas station plastered with signs for Dr. Pepper and Red Man Chewing Tobacco.

We’ve been here before, most memorably with “Bonnie and Clyde,” but also with Roger Corman’s seamy examination of the Barker family in “Bloody Mama.” Robert Aldrich’s new film owes something to both. To “Bonnie and Clyde” for its convincing period feel, and to “Bloody Mama” for its treatment of a violent, sexually twisted family of criminals.

Why this sort of material should be fascinating to American directors just now is hard to say. John Frankenheimer, for example, covered similar backwoods territory in “I Walk the Line,” and now comes Aldrich. The one thing Aldrich has going for him, however, is a fine sense of depraved melodrama. He seems at home working with characters who come out of the Gothic novel via Screen Romances, and his early films in this genre include “Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte,” “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?” and the gruesome pseudo-ghost story, “The Legend of Lylah Clare.”

Even “The Grissom Gang,” which looks like a 1930s gangster movie at first, is really in the Gothic tradition. Aldrich keeps his camera inside a lot of the time; there are a few barns, a few roads and a few wheat fields, but most of the film was shot in sound stages, and there’s a nice symbolic moment where the kidnapped girl pulls back the draperies in her room and finds a brick wall instead of a window. Aldrich is trying to work his way into the minds of his weirdly assorted cast of characters; he doesn’t want to see them as symbols of a particular moment in history, as Arthur Penn did in “Bonnie and Clyde.”

The story, which is too complicated for its own good, is about the kidnapping of a rich Kansas City socialite (Kim Darby) by a group of 10-thumbed amateurs who are later eliminated by the Grissom family. The family boss is the tough, hard-nosed mother (Irene Dailey), and the family front man is the sleek Tony Musante. But the one they’re all afraid of is Slim (Scott Wilson, who played the taller killer in “In Cold Blood“). He’s a violence-prone, sexually repressed maniac who loves his mother not wisely and not too well. When the gang holes up with their captive, he falls in love with her.

Having established a conventional sort of gangster atmosphere, Aldrich now zeroes in on his characters. He has them under tremendous stress, he has shown us their weaknesses and now he plays with a few unusual possibilities. Will the girl’s millionaire father want her back, now that she’s “not the same goods he paid a million for,” as Musante suggests? Will the repressed younger brother find a release for his pent-up emotions, or will he turn on the girl and kill her? Will the brothers maintain their uneasy truce? What about Ma?

If questions like this sound melodramatic, that’s because the movie is deliberately melodramatic, and to such an overdone degree that (if you suspend your sanity for an hour or so) you can almost wallow in it. Everyone screams, shouts, flashes knives at each other and sweats a lot. The girl takes to drink. The kid brother locks her in a combination cage and love nest that reminds us of “The Collector.”

When the movie’s over, you can’t exactly say what it’s meant to you. Aldrich is so much a stylist that the film, for all its labored melodrama, doesn’t seem to suffer for the usual reasons. You can’t hold the plot, the dialog or the grotesque characterizations against it, because somehow Aldrich has gotten everything functioning well on at least one fundamental level. Take this as a horror film (a Gothic horror film, where the dangers are human and not science-fictional) and you may enjoy it even more than it deserves.