I’ve been told that the one test vocational aptitude test-takers find the most frustratingly difficult to complete is the three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, except for the small percentage who become architects or other professions that require the exceptional ability to imagine in three dimensions. Filmmakers have their own exceptional ability for visual storytelling, making one-dimensional images projected onto a screen into a world that encompasses time, emotion, and narrative. In filmmaker Yael Melamede’s biographical film about her mother, pioneering Israeli architect Ada Karmi-Melamede, the two ways of seeing the world and telling a story come together. She uses split-screen images of her mother during some of their interviews, one face-to-face, the traditional documentary talking-head shot, one from the side, as though she wants to convey the dimensionality of a building in an academic lecture on architecture, and as though she wants us to be near but at the same time at a remove. At times, we see Yael asking her mother questions behind a camera. Then they are face to face. Finally, they are half a world away, on a video call.

The film also explores duality in its subjects. It is both an exploration of Karmi-Melamede’s extraordinary professional achievements and the way she thinks about buildings and our relationship to them, and also an exploration of her life and relationships with her family. This includes her father (whose buildings connect her to him), her brother (her partner on one of her biggest projects), and her decision to leave her husband and children in New York and return to Israel to continue her career.

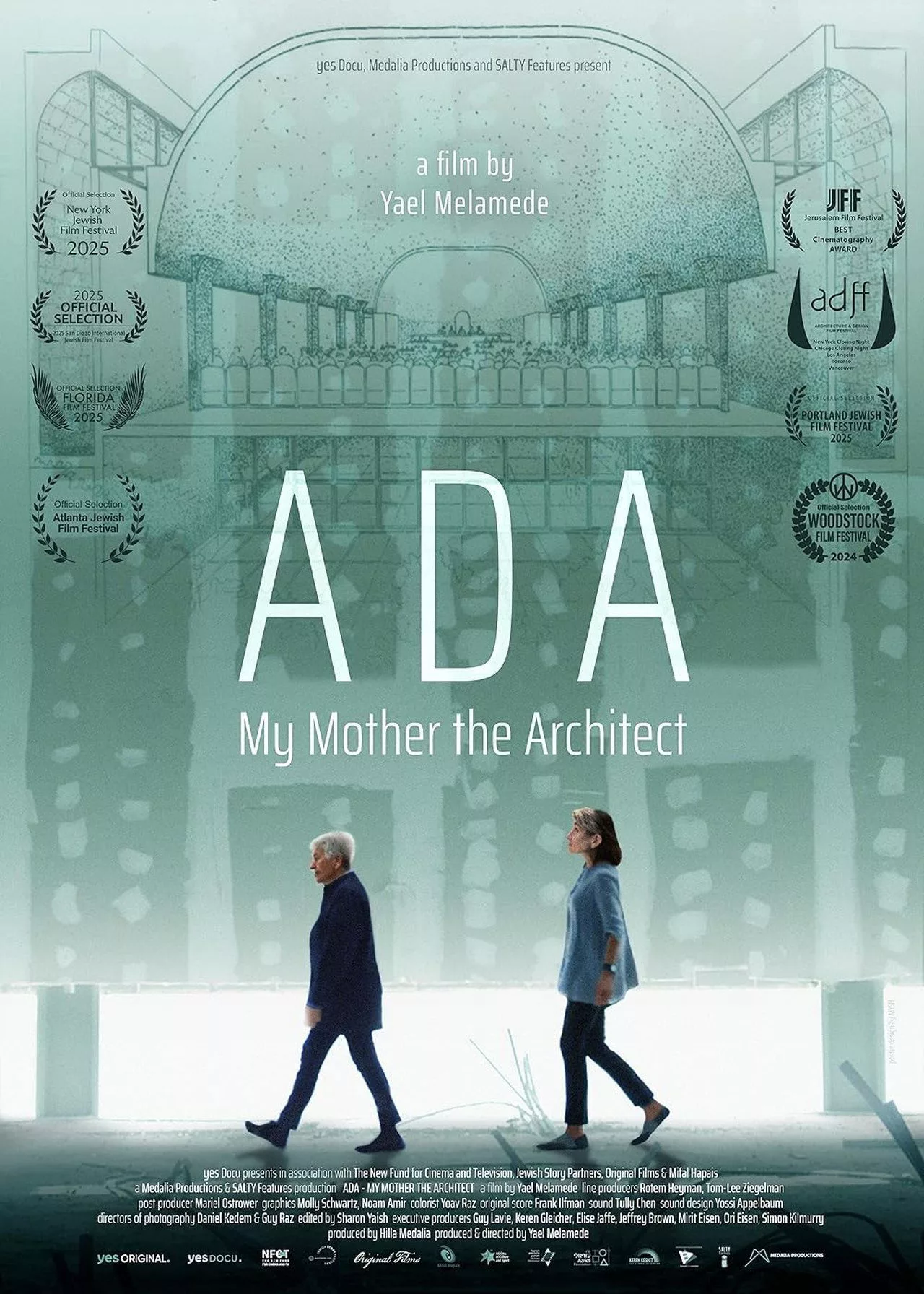

This is the latest in a small but fascinating category of documentaries about famous parents, including one that might make a good double-feature with this one: “My Architect,” about Louis Kahn. Others include films made by their children about musician Quincy Jones, cinematographer Haskell Wexler, and CIA spymaster William Colby.

To Ada Karmi-Melamede, family and architecture are one. She was given Israel’s highest award for architecture. So were her father, Dov Karmi, its first recipient, and her brother, Ram Karmi. Because they were working just before and then after Israel became a country in 1948, it is said that her family “built Israel from the ground up,” including public works like the Ben Gurion Airport, the Supreme Court Building, the largest concert hall in Tel Aviv, museums, universities, apartment buildings, and many more. Their work established the foundational style of Israeli architecture: modern, sometimes brutalist. Yael also became an architect. She designed her mother’s home and office before she left the field to become a filmmaker.

Ada’s work is considered both literally and metaphorically ground-breaking. She is dedicated not just to the shape and function of the building, but also to the experience of walking through it. She says she is a “sculptor of light.” The one time she worked with her brother was when they won the competition to design the country’s Supreme Court building. They did not want the intimidating grandeur of the white marble columns and sky-high ceilings in the entryway to the US Supreme Court building. Ada explains that they did not want people to feel small when entering the building. The Israeli Supreme Court is located at the intersection of four key locations: the Old City, Parliament, the Bus Station, and the Mediterranean. The entryway is narrow, so “you don’t feel small. You are the center.” As the floor rises, you walk toward a huge window with a gorgeous view of Jerusalem, reminding everyone who comes into the building, including those who work there, of the traditions, aspirations, and people the Court must honor. Another member of the family played a role as well. Ada was not a fan of shiny floors, but her mother persuaded her that they look clean, and that was the feeling she wanted to create. The result, she says, makes people look like they are walking on water.

A New York Times architectural critic appears in the film, reading his review of the Supreme Court building: “A nation that has shown little architectural leadership has produced a building that can stand as an example to the world of the potential for public works to reflect a culture’s highest aspirations.” And then he sighs that Israel itself has not always lived up to those aspirations.

Ada describes more emotion in talking about arguing with Ram about the building (“a lot of wet eyes”) than in talking about her children. “You are the child of your father,” she says to her filmmaker daughter, dismissive when Yael remonstrates that her only custodial parent traveled a lot for business. When asked about leaving her children half a world away, Ada responds about herself, not the impact on them. “I had a framework that compensated for many of my losses. It kept me sane.” Even when she begins to tear up at one point, her face remains stoic.

The word “roots” comes up in many contexts as Ada talks about her life and work. She describes how a building may or may not be rooted in the ground. Her connections to her work and the country she lived in before it became a country are where her roots are. Both are intermingled when a project, as so often happens in Israel, has to work around the archeological dig they discovered when they first excavated the site.

When Yael asks Ada about architecture, her mother is spellbindingly eloquent, even poetic. You may never walk through a building the same way again after you hear Ada describe what she hopes to achieve (and what she is determined to avoid) as people see, walk through, live, and work in what she creates. When Yael asks her mother more personal questions, Ada refuses to answer, which is, of course, itself an answer. Those responses may inspire you to call your family, or perhaps make a film about one of them.