“My talent was the weapon, the power, the way for me to fight. It was the one way I might hope to affect a man’s thinking.”

“I think it (the March on Washington in 1963) was the most American day in the history of our country, save for perhaps the Battle of Bunker Hill. Or, maybe the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It’s to be put on that level, for me.”

― Sammy Davis, Jr.

Bijan Bayne reminds us of Hollywood’s history with the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, sixty years ago. There are lessons for us today. So many people of different races and ages and political beliefs came together for the cause of equality and humanity. Attendees included entertainers as diverse as Paul Robeson, Lena Horne, and Sammy Davis, Jr. to Charlton Heston. Judy Garland served on the Planning Committee. And, of course, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his historic “I Have A Dream” speech. The observance of the March will take place this Saturday, August 26, in Washington, DC. — Chaz Ebert

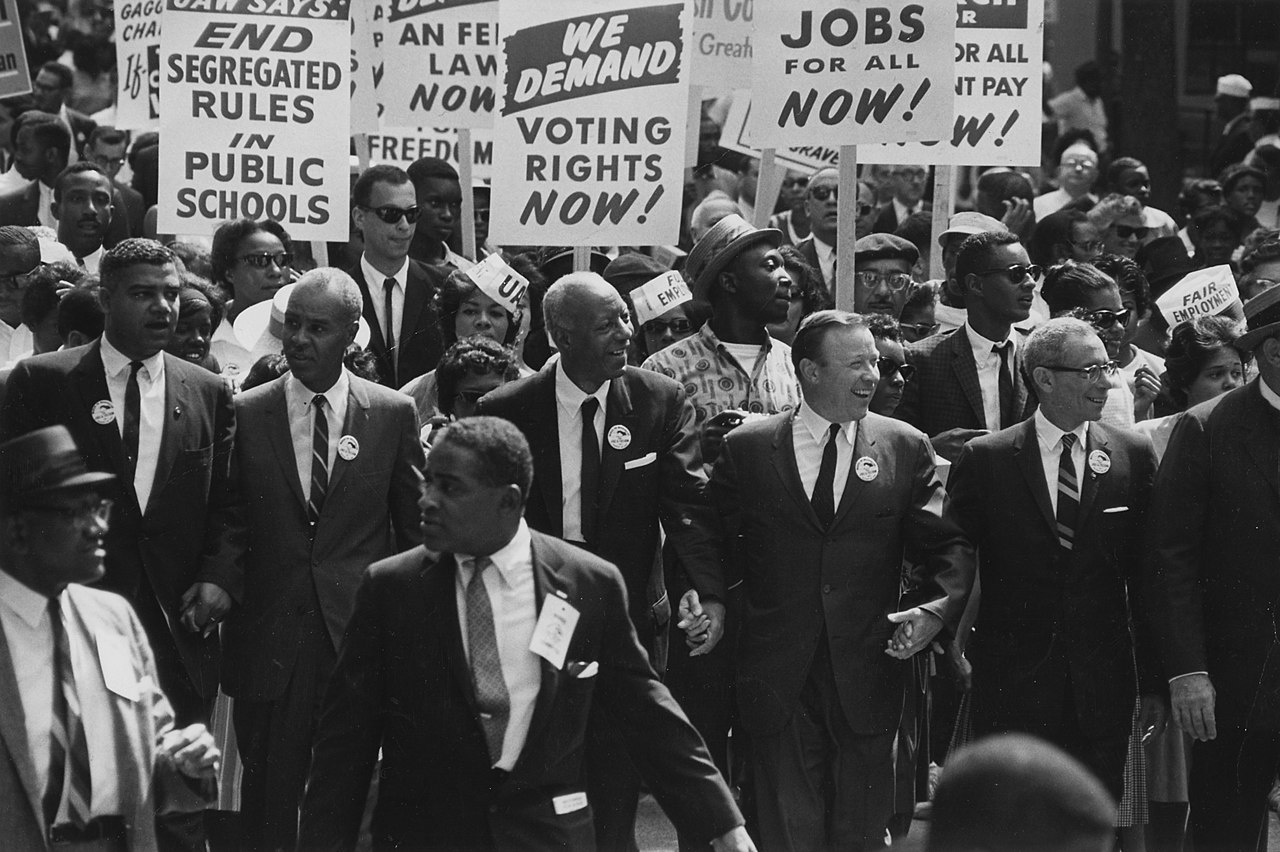

On August 28, 1963, approximately 250,000 people collected on The National Mall in Washington, D.C. for The March for Jobs and Freedom. The three major U.S. TV networks broadcast the event live, meaning hundreds of millions of viewers watched the demonstration, among them President John F. Kennedy (who had both discouraged the march and recommended D.C. close its liquor stores). Nearly 6,000 Washington police were on duty, in addition to 2,000 National Guard, 5,000 regular military, and 19,000 emergency troops in the surrounding suburbs. Celebrities and entertainers were also warned by authorities not to attend. James Garner later wrote that an FBI agent called all the major stars the night before the affair, warning them that they would not be protected.

This did not dissuade stars from attending and even speaking. Those who supported human rights had a history of doing so. Their generation changed show business forever.

The cadre of stars who visibly supported The March for Jobs and Freedom risked life, limb, and their careers. They were a beacon of hope to aspirants for inclusion. Each knew they could be canceled by the culture, rejected by fans, and closely monitored by law enforcement agencies. But they also realized the symbolic strength of their stance and the power of their collective platforms.

To start, Judy Garland served on the planning committee. Though Garland missed the event due to obligations of her TV variety series (which featured Black guests such as Count Basie, Lena Horne, and Nat “King” Cole in July and August tapings of 1963), a who’s who of performers did march. The producer of those summer Garland shows was Norman Jewison, later to direct Sidney Poitier in 1967’s “In the Heat of The Night” (he had replaced George Schlatter, who would go on to produce “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In”). Lena Horne, Nina Simone, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Franciosa, James Garner, Burt Lancaster, Harry Belafonte, Diahann Carroll, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, Charlton Heston, Gregory Peck, Rita Moreno, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward participated in The March on Washington. Tony Curtis and Robert Ryan, who had portrayed racists in “The Defiant Ones” (co-starring with Poitier) and “Odds Against Tomorrow” (with Belafonte), respectively, lent fiscal support.

Married couple Dee and Davis emceed the program. It began with freedom and folk songs from Joan Baez, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Odetta. Women activists Rosa Parks and Daisy Bates (substituting for Myrlie Evers, Medgar Evers’ widow, whose flight to D.C. arrived late) addressed the growing throng briefly. Even more brief was Horne, who shouted, “Freedom!” That all happened between 9 a.m. and 11:30 am, as buses, trains, carpools, and locals on foot ascended on The Mall. Gospel queen Mahalia Jackson started the main program with her rendition of the U.S. national anthem. Attendees and media noticed the famous entertainers near the Lincoln Memorial steps as they conferred with each other and their recent friends, such as writer James Baldwin. Their individual roads to activism speak to what was broken about this country and their industry.

In the early 1940s, when she was 23, Lena Horne headlined New York City’s Cafe Society, the only racially integrated nightclub downtown. It was there she met human rights leader and vocalist Paul Robeson. She later recalled, “He said, ‘Look, you’re a Negro, and that is the whole basis of what you feel, and it’s the basis of what you will become.’ And he gave me identity—he grounded me.” She also got to know author Langston Hughes. Influenced by such intellectuals, Horne joined the Council for African Affairs and the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee. She refused to portray maids or mammies in movies.

By the late 1940s, she was a member of the Progressive Citizens of America.

Lena Horne told David Richards of the Washington Post on April 29, 1983, 20 years after The March On Washington, “Where I got racism was in the clubs and cabarets. I just finished playing St. Louis, and I lived at the Chase Hotel. The first time I worked at the Chase, I couldn’t come in through the front door. There was the Clover Club in Miami. Sweet job, but no blacks were allowed in the audience. And the Savoy Plaza in New York. Sometimes the hotels would take me, but not the guys in the band. It wasn’t until the late ’50s that things began to change because we did business. Vegas started to swing open. But we couldn’t have changed nothin’ if we hadn’t made money.”

She said of the Chase, “If I’m good enough to sing there, I’m good enough to stay there.” She balked when film makeup artists attempted to put dark brown cream on Horne’s face to match her complexion with fellow Black cast members. Max Factor developed his tone of “Light Egyptian” for Horne.

Horne told Richards, “They hadn’t made me a maid, but they hadn’t made me into anything else either. So, I just became a little butterfly pinned up against the wall, singing all these lovely songs. Singing my heart away in Hollywood,”

Belafonte gave a speech cautioning that discrimination would lead to “artistic sterility” and that the entertainment business should do everything possible to bring freedom to all.

Black performers called the Las Vegas of the 1940s “The Mississippi of the West.” Lena Horne played mobster Ben “Bugsy” Siegel’s Flamingo hotels and casino in 1947, Pearl Bailey worked the El Rancho in 1948, and Nat King Cole and Katherine Dunham played the El Rancho in 1951. None could stay at the lounges. The Black stars roomed in homes off the Strip or Black-owned boarding houses in West Las Vegas. When Horne worked the Flamingo, she was told to avoid its lounges. The housekeeping staff burned her bedclothes after she checked out.

In April 1953, dance group Sammy Davis, Jr. and the Will Maston Trio became the first Blacks to headline a show on The Strip. They earned $5,000 a week. In 1954, Frank Sinatra named them his opening act at the Sands. By 1954, the trio (consisting of Sammy, his dad Sam, Sr., and his play “Uncle, Will Mastin) were making $7,500 a week to headline at the Frontier on The Strip. Due to Sinatra’s clout, they earned complimentary stays, including meals and drinks. That year, Davis lost an eye in an auto accident. During his comeback, he made $25,000 a week at The Sands, living in the swankest room in the house. By the early 1960s, Davis was palling around Vegas with not only Sinatra but Peter Lawford, Joey Bishop, and Dean Martin (then known as The Hollywood Clan), and all refused to perform or patronize segregated casinos. The Strip changed its ways, even hiring Black croupiers, bar staff, and showgirls. No more entering hotel kitchens for the likes of Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat “King” Cole.

Before this development, Cole had been refused entry by a casino doorman. “But that’s Nat King Cole,” said a white man with the singer. “I don’t care if he’s Jesus Christ,” the doorman retorted, “He’s a n—–, and he stays out.” Josephine Baker once sat on the stage of the El Rancho, refusing to perform because Blacks weren’t admitted there. Baker attended The March on Washington.

In 1955, the same year Emmett Till was murdered and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus, the Moulin Rouge opened as an integrated Vegas casino hotel—with former heavyweight champ Joe Louis as its greeter. The Rouge, as locals called it, became such a hit rival casinos began paying white showgirls overtime not to flock to the inclusive hotel to watch shows after their own shifts.

In his 1965 memoir Yes I Can, Sammy Davis, Jr. wrote, “In Vegas for 20 minutes, our skin had no color. Then the second we stepped off stage, we were colored again. The other acts could gamble or sit in the lounge and have a drink, but we had to leave through the kitchen with the garbage.” Also, in 1955, Belafonte decided to integrate the swimming pool at The Riviera- a popular Vegas Strip hotel.

Today, many like to think of Dr. King as universally popular among his grassroots Black contemporaries and that the cause of ethnic equality drew undivided community support. Davis’ recollection of his efforts to fundraise for The Movement in his native Harlem illustrates that this was not the case. In Yes I Can, he said a wholesale meat owner told him of King, “No, I do not approve of what he’s doing.”

Davis: “Are you telling me you don’t want integration?”

“Not the kind he’s goin’ around begging for. Smarten up, Mr. Davis. The only integration you’ll ever see in this country is when ofay blood runs in the gutter and mixes with good colored blood.”

A hotel owner said, “Sammy, I’m the first one to say something should be done.”

Sammy: “But by somebody else, right?”

A supermarket owner, whom Davis called an “old friend,” told him, “Where do you get your nerve coming up here telling me how to be colored? Why as far back as I can remember you’ve been ashamed to death that you’re colored.”

A nightclub owner: “Colored people never did anything for me. All I ever got outa being colored is more room on the subway ’cause white people don’t wanta sit next to me.”

Because Sammy had wed Swedish actress May Britt, when he was introduced to the delegates gathered at the 1960 Democratic National Committee Convention at the Los Angeles Sports Arena in 1960, he was booed by the all-white Mississippi delegation seated up front. His marriage (Frank Sinatra was his best man) caused a rift between Sinatra and Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy. It was said that JFK snubbed Davis by refusing to invite him to perform at his inauguration.

In his autobiography, James Garner said Republicans approached him to run for office in 1962. When he told them he was a Democrat, they said they didn’t care (in those days, popular Oklahomans, such as former college football coach Bud Wilkinson, ran for statewide office). Garner often told people he met his wife, Lois Clarke, at a party for Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic Party presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956. Garner became a member of SAG’s board of directors in 1960. He was twice elected Second Vice President.

Tony Franciosa was known for his roles in “A Face in the Crowd” and “The Long, Hot Summer.” In 1963, he joined Marlon Brando and Paul Newman (a “The Long, Hot Summer” co-star) in Gadsden, Alabama, in 1963 for a desegregation drive. “Regardless of the great struggle we’re going through,” Franciosa said to the Gadsen crowd. “The greatest thing I see here is joy.”

Sidney Poitier refused roles he deemed denigrating or subservient. Not long after The March, he and Belafonte went to Greenwood, Mississippi, for Freedom Summer. The two West Indian superstars stuffed $70,000 cash into a bag to help support local voter registration. Ku Klux Klan members chased the actors out of Greenwood.

When “In the Heat Of The Night” (1967) was being produced, he refused to work on location in Mississippi. During filming in Southern Illinois, he slept with a firearm under his bed. He also insisted that in the scene where he is slapped by a wealthy white tycoon that he accuses of murder, his character slaps the man back. Poitier demanded that the sequence be shown in every version of the movie screened in America.

March attendee Joanne Woodward was from Greater Atlanta. At the world premiere of Gone with the Wind in Atlanta, nine-year-old Woodward ran up and sat on Laurence Olivier’s lap. Olivier was married to the film’s co-star, Vivien Leigh.

Woodward attended segregated LSU.

She later campaigned for Gore Vidal when he ran for the House of Representatives in the early 1960s. Woodward became a member of the board of the Center for Defense Information, a watchdog association focused on the U.S. military. She served on the National Women’s Conference to Prevent Nuclear War. Her husband, Paul Newman, followed his March participation by narrating a documentary about the Civil Rights Movement. The outspoken Newman was on President Richard Nixon’s famous “enemies list.” He and Steve McQueen, Barbara Streisand, and Dustin Hoffman formed First Artists to produce their own features (much as Sinatra and Belafonte separately had done before them).

Some readers may be surprised to learn Charlton Heston attended The March. Before he became associated with conservative causes, he said, “That march, which was an example of peaceful, lawful civil demonstration, was a responsible act. It was a democratic process, in a way, and if you believe in democracy, you have to believe in how it works. As for Hollywood, hell, this is no longer the bad old days.” Heston was elected president of the Screen Actors Guild. He switched political parties in 1987. In 1998, he was elected president of the National Rifle Association.

Joseph Mankiewicz, who wrote and directed 1958’s “The Quiet American,” also attended The March. He shifted the premise of “The Quiet American” to one critical of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the Red Scare.

Though McCarthyism tainted Belafonte, Ed Sullivan himself invited Belafonte onto his variety show in 1953. And yet, even as he was accorded this lucky break, Belafonte couldn’t just shut up and sing. The calypso crooner helped Sullivan understand the Black fight for freedom by comparing it to the Irish resistance against the British. Belafonte, who was producing his own films by 1959, donated $40,000 to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Davis and Poitier were also major donors to The Movement, both financially and via benefit performances. It was Belafonte who brought singer Tony Bennett into this circle.

Immediately after The March, Hollywood Roundtable was produced by the United States Information Agency. James Baldwin, Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Charlton Heston, and Joseph Mankiewicz discussed human rights challenges and solutions on a televised panel. During the filming, Brando called for reparations for Native Americans. Part of Brando’s sentiment for the oppressed came from his mom, Dorothy Pennebaker Brando. She had encouraged a young man from their native Omaha to take up theater: Henry Fonda.

In 1972, Belafonte told the New York Times, “I felt very optimistic at the time of the March on Washington. Now I am more cautious about my optimism. After all, at the time of the march, we had more to work with. We had Martin Luther King, the Kennedy Administration, the Peace Corps.”

The March on Washington was a success by any measure—crowd turnout, worldwide messaging, peaceful action, and resultant Congressional legislation. JFK admitted to Oval Office viewers of the protest that Dr. King was “very good.” After the president was assassinated three months later, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, fought tooth and nail against a staunch segregationist wing of the U.S. Senate, some of whom the Texan had served with as Majority Leader, to help pass the Civil Rights Bill of 1964.

Sammy Davis, Jr. said, “I think it was the most American day in the history of our country, save for perhaps the Battle of Bunker Hill. Or, maybe the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It’s to be put on that level, for me.”

He died on May 16, 1990. In his will and testament, he had bequeathed $100,000 to Morehouse College, the alma mater of Dr. King.