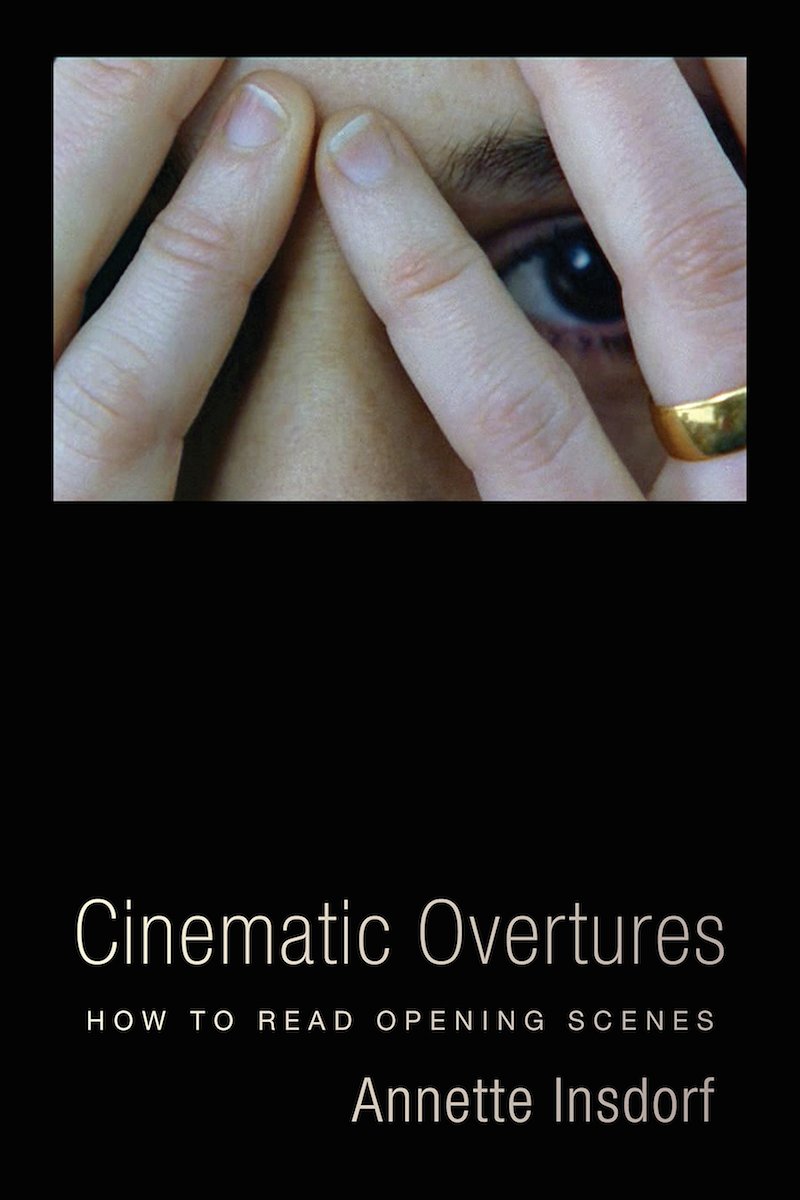

Cinematic Overtures: How to Read Opening Scenes is the latest book written by Annette Insdorf, a professor in the Graduate Film Program of Columbia University’s School of the Arts and host of the Reel Pieces series at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y. The book will be published by Columbia University Press this November. Here the official synopsis for the book…

A great movie’s first few minutes provide the key to the rest of the film. Like the opening paragraphs of a novel, they draw the viewer in, setting up the thematic concerns and stylistic approach that will be developed over the course of the narrative. A strong opening sequence leads the viewer to trust the filmmakers. Other times, opening shots are intentionally misleading as they invite alert, active participation with the film. In Cinematic Overtures, Annette Insdorf discusses the opening sequence so that viewers turn first impressions into deeper understanding of cinematic technique.

From Joe Gillis’s voice-over in “Sunset Boulevard” as he lies dead in a swimming pool to the hallucinatory opening of “Apocalypse Now,” from the stream-of-consciousness montage as found in Hiroshima, mon amour to the slowly unfolding beginning of “Schindler’s List,” Cinematic Overtures analyzes opening shots from a range of Hollywood as well as international films. Insdorf pays close attention to how the viewer makes sense of these scenes and the cinematic world they are about to enter. Including dozens of frame enlargements that illustrate the strategies of opening scenes, Insdorf also examines how films explore and sometimes critique the power of the camera’s gaze. Along with analyses of opening scenes, the book offers a series of revelatory and surprising readings of individual films by some of the leading directors of the past seventy-five years. Erudite but accessible, Cinematic Overtures will lead film scholars and ardent movie fans alike to greater attentiveness to those fleeting opening moments.

For a sneak peek at the films covered in this book, here is the table of contents (the linked movie titles below will direct you to Roger’s reviews; Annette’s essays on the films will be available in her book):

The Crafted Frame (Saul Bass, “Talk to Her,” “Knife in the Water,” “Camouflage”)

The Opening Translated from Literature (“The Conformist,” “The Tin Drum,” “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” “All the President’s Men,” “Cabaret“)

Narrative Within the Frame: Mise-en-Scène and the Long Take (“Touch of Evil,” “The Player,” “Aguirre: The Wrath of God,” “The Piano,” “Bright Star,” “In Darkness“)

Narrative Between the Frames: Montage (“Z,” “Hiroshima, mon amour,” “Seven Beauties,” “Schindler’s List,” “Three Colors: Red,” “The Shipping News,” “Shine“)

Singular Point of View (“The Graduate,” “Taxi Driver,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Come and See,” “Lebanon,” “Good Kill“)

The Collective Protagonist (“La Ciudad,” “3 Backyards,” “Little Miss Sunshine,” “Le Bal,” “Day for Night,” “A Separation,” “Where Do We Go Now?“)

Misdirection/Visual Narration (“The Hourglass Sanatorium,” “Before the Rain,” “Ajami,” “Under Fire,” “The Conversation,” “Rising Sun,” “Psycho,” “The Truman Show“)

Voice-Over Narration/Flashback (“Sunset Boulevard,” “American Beauty,” “Fight Club,” “Badlands“)

Roger Ebert is quoted throughout the book, and Insdorf provided us with three key excerpts that include his insights…

On Werner Herzog‘s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God“

The beginning of “Aguirre” can move from heaven to earth, but by the end of the film, the camera only goes around in circles. The last shot is as striking as the opening: from the whirling camera, we see the demented, lopsided Aguirre alone on his raft, in command only of corpses and hundreds of chattering little monkeys. It invokes the image of the whirlpool that dominates an earlier sequence. Listening to the film’s dialogue in the German language provides another layer of meaning. When Kinski’s conquistador character says, “we need a leader” using the word “fuhrer,” the film becomes a post-war meditation on German guilt. He proclaims, “we’ll produce history as others produce plays.” If the characters in this primordial landscape search for gold, it is power that he really seeks. As Ebert wrote, “Of modern filmmakers, Werner Herzog is the most visionary and the most obsessed with great themes. … He wants to lift us up into realms of wonder. Only a handful of modern films share the audacity of his vision; I think of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ and ‘Apocalypse Now.’”

On Elem Klimov’s “Come and See”

Nature endures and regenerates whether humans act nobly or destructively. In fact, a film released the same year, Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah,” is also anchored in landscapes that no longer reflect the wartime horrors they witnessed forty years earlier. Whereas Roger Ebert interpreted the final scene of “Come and See” as a fantasy—“the Mozart descends into the film like a deus ex machina, to lift us from its despair. We can accept it if we want, but it changes nothing. It is like an ironic taunt”[i]—Klimov might be elevating the frame to a pantheistic vision of the universe. The last word we hear from the choral voices of Mozart’s “Requiem” is Amen.”

On Milcho Manchevski’s “Before the Rain”

As Roger Ebert wrote, “The construction of Manchevski’s story is intended, then, to demonstrate the futility of its ancient hatreds. There are two or three moments in the film … in which hatred of others is greater than love of one’s own. Imagine a culture where a man would rather kill his daughter than allow her to love a man from another culture, and you will have an idea of the depth of bitterness in this film, the insane lengths to which men can be driven by belief and prejudice.”

Cinematic Overtures: How to Read Opening Scenes will be available for purchase in November 2017.