Rising Sun, a novel by Michael Crichton about the cutthroat competitive tactics of a giant Japanese conglomerate, was accused of Japan-bashing. Few such complaints are likely to be lodged against the movie, which uses the world of business as a backdrop for a much more conventional Hollywood plot, in which Sherlock Holmes and Charlie Chan meet “Basic Instinct.” All of the real villains in the film are Americans, and few of the Japanese are developed much beyond the complexity necessary to make them interesting foils for the cops.

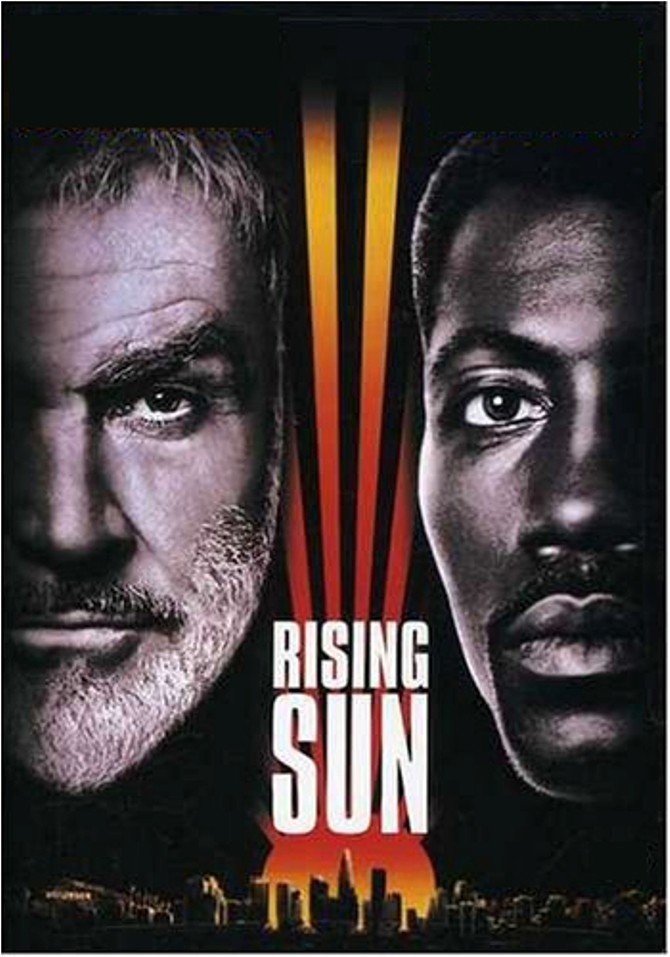

The movie takes place in modern Los Angeles, where a Japanese multinational corporation operates out of one of those towering skyscrapers where the security guards seem to know everybody’s business. A kinky murder takes place during a social function in the building: A sexy model is found apparently strangled to death on the table in the board room. Most of the clues lead directly to Eddie Sakamura (Cary Hiroyuki-Tagawa), the woman’s lover, who occupies a shadowland between business and crime, and acts as if he has spent a good deal of time studying Al Pacino as “Scarface.” An L.A. cop (Harvey Keitel) is on the scene in moments, but this is a touchy case because the Japanese don’t want to cloud the image of their newly launched corporation. So the LAPD turns to its “special liaison” unit and calls in a shadowy, legendary cop named John Connor (Sean Connery) and his partner, Web Smith (Wesley Snipes).

From the moment Connor and Smith arrive on the scene, the movie turns into a variation on the cop buddy movie. In fact, it reaches all the way back to perhaps the earliest versions of the formula, Sherlock Holmes stories and Charlie Chan movies. Connery plays a Holmes/Chan clone who is unnaturally prescient and wise, and Snipes is Dr. Watson/No. 1 Son, the straight man, always missing the clues until the older man points out how obvious they are.

This is a routine that quickly grows tedious. Connery has any number of speeches in which he brilliantly analyzes the “Japanese mind,” predicts what tactics will be used, penetrates ploys, anticipates strategies, and in general seems able to see through walls and predict the future. Many of his speeches have a guru-esque quality, as when Snipes is thrilled by a new lead and Connery intones: “When something looks too good to be true, then it’s not true. Everything she said about Eddie might have been true. But the real question is, why was she saying it?” The dialogue grows platonic: Snipes: “Look, this Julia woman accidentally . . .” Connery: “Nothing is happening accidentally. She’s a messenger.” Snipes: “You think someone sent her? OK, who?” Connery: “The bad guys.” Thank you very much.

Eventually Connery’s Sherlock act demands a response, and so the movie provides the cops with a visit to an inner-city black neighborhood, for little other purpose than for Snipes to turn the tables.

Much of the criminal investigation centers on a crucial fact: The identity of the killer may have been captured on a laserdisc security system, but the disc seems to have been altered to conceal the crucial moments when the murderer’s face might be visible. The cops work with a computer video expert named Jingo (Tia Carrere), who is able to undo the computer dirty work, leading to the discovery of the person who may or may not be the killer, and certainly looks guilty as hell.

In the midst of servicing this cooked-up plot, the movie genuflects occasionally in the direction of its ostensible subject, American-Japanese competition. It’s clear, however, that director Philip Kaufman didn’t consider it one of his missions to make any sort of significant statement on this theme. Most of the Japanese in the film have motives that are easily understandable and often blameless, and they don’t seem to have tactics so much as the ability to make other people believe they have tactics. Much more is attributed to the Japanese here than is ever seen being done by them.

What perturbs us the most about competition with the Japanese, I sometimes think, is that we don’t resent their methods – we envy them. Descriptions of Japanese business tactics are almost always linked with gloomy musings that we should be doing the same thing.

The Sean Connery character in “Rising Sun” is seen to be good because he has spent much time in Japan, loved a Japanese woman, and absorbed so much of the Japanese character that he is damn near as smart as Mr. Miyagi.

The murder investigation itself is a large red herring; the end of the movie adds so many variants and surprises that the plot loses any degree of credibility, and is revealed as essentially just as excuse for the thriller set-pieces. Even then it fails, because the alert viewer can easily determine the identity of the real killer by using my Law of Economy of Characters, which teaches us that since movie budgets cannot afford unnecessary salaries, any apparently unnecessary or extraneous major character is undoubtedly the villain (remember, for example, Whitney Houston’s sister in “The Bodyguard“).

“Rising Sun” is, of course, a slick, goodlooking movie. Kaufman is one of the best American directors (“The Right Stuff,” “The Unbearable Lightness of Being“), and he has a sure visual sense. But the screenplay by Kaufman, Crichton and Michael Backes is not about much of anything important, and Connery’s deep penetrating wisdom takes away some of the suspense: If he knows everything that’s going to happen, why keep us in the dark?