“Cabaret” explores some of the same kinky territory celebrated in Visconti’s “The Damned.” Both movies share the general idea that the rise of the Nazi party in Germany was accompanied by a rise in bisexuality, homosexuality, sadomasochism, and assorted other activities. Taken as a generalization about a national movement, this is certainly extreme oversimplification. But taken as one approach to the darker recesses of Nazism, it may come pretty close to the mark. The Nazi gimmicks like boots and leather and muscles and racial superiority and outdoor rallies and Aryan comradeship offered an array of machismo-for-rent that had (and has) a special appeal to some kinds of impotent people.

“Cabaret” is about people like that, and it takes place largely in a specific Berlin cabaret, circa 1930, in which decadence and sexual ambiguity were just part of the ambience (like the women mud-wrestlers who appeared between acts). This is no ordinary musical. Part of its success comes because it doesn’t fall for the old cliché that musicals have to make you happy. Instead of cheapening the movie version by lightening its load of despair, director Bob Fosse has gone right to the bleak heart of the material and stayed there well enough to win an Academy Award for Best Director.

The story concerns one of the more famous literary inventions of the century, Sally Bowles, who first came to life in the late Christopher Isherwood’s ‘Berlin Stories,’ and then appeared in the play and movie ‘I Am a Camera’ before returning to the stage in this musical, and then making it into the movies a second time — a modern record, matched only by Eliza Doolittle, I’d say.

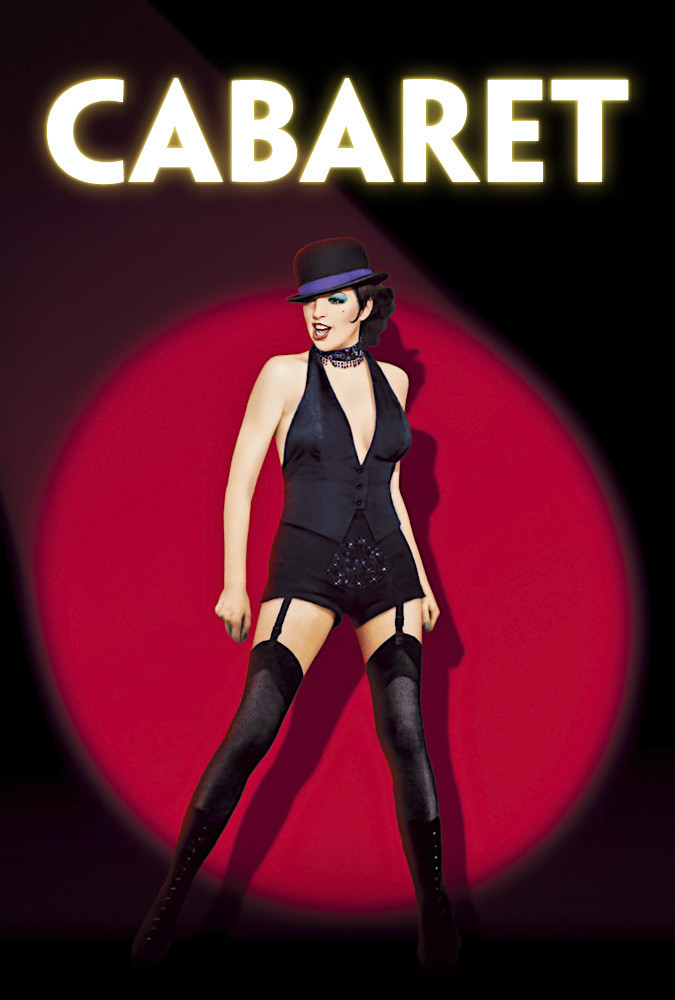

Sally is brought magnificently to the screen in an Oscar-winning performance by Liza Minnelli, who plays her as a girl who’s bought what the cabaret is selling. To her, the point is to laugh and sing and live forever in the moment; to refuse to take things seriously — even Nazism — and to relate with people only up to a certain point. She is capable of warmth and emotion, but a lot of it is theatrical, and when the chips are down she’s as decadent as the “divinely decadent” dark fingernail polish she flaunts.

Liza Minnelli plays Sally Bowles so well and fully that it doesn’t matter how well she sings and dances, if you see what I mean. In several musical numbers (including the stunning finale “Cabaret” number), Liza demonstrates unmistakably that she’s one of the great musical performers of our time. But the heartlessness and nihilism of the character is still there, all the time, even while we’re being supremely entertained.

Sally gets involved in a triangular relationship with a young English language teacher (Michael York) and a young baron (Helmut Griem), and if this particular triangle didn’t exist in the stage version, that doesn’t matter. It helps define the movie’s whole feel of moral anarchy, and it is underlined by the sheer desperation in the cabaret itself.

Here the festivities are overseen by a master of ceremonies (Joel Grey, whose performance received an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor) whose determination to keep the merriment going, at whatever psychic cost, has a poignant compulsiveness. When the song Cabaret comes at the end, you realize for the first time that it isn’t a song of happiness, but of desperation. The context makes the difference. In the same way, the context of Germany on the eve of the Nazi ascent to power makes the entire musical into an unforgettable cry of despair.