Lina Wertmuller’s “Seven Beauties” is about Pasqualino, a little man who absentmindedly wanders through the Italian fascism of the prewar years before finally being imprisoned by the Nazis. That doesn’t make it unusual; there have been a lot of Italian films exploring the experience of World War II. What does make “Seven Beauties” unique – what makes it one of the strangest and most intriguing of recent European films – is that Pasqualino is a fool. He’s not brave, or bright, or even cynical or cowardly. In his best moments he’s an opportunist, and at his worst a devout pawn.

He does not, of course, suspect this about himself. He’s obsessed with notions of honor, and even goes so far as to assume he possesses a great deal of honor. His honor is a totally macho thing, involving dim-witted ideas about the proper behavior of males in the face of insults to their sisters. And he has his work cut out for him since there are seven sisters in his family, each one more unattractive than the last, each one, in his eyes, a potential candidate for ruin. When the worst finally happens, when one of his sisters takes up with a pimp and goes to work in a brothel, he knows what he has to do.

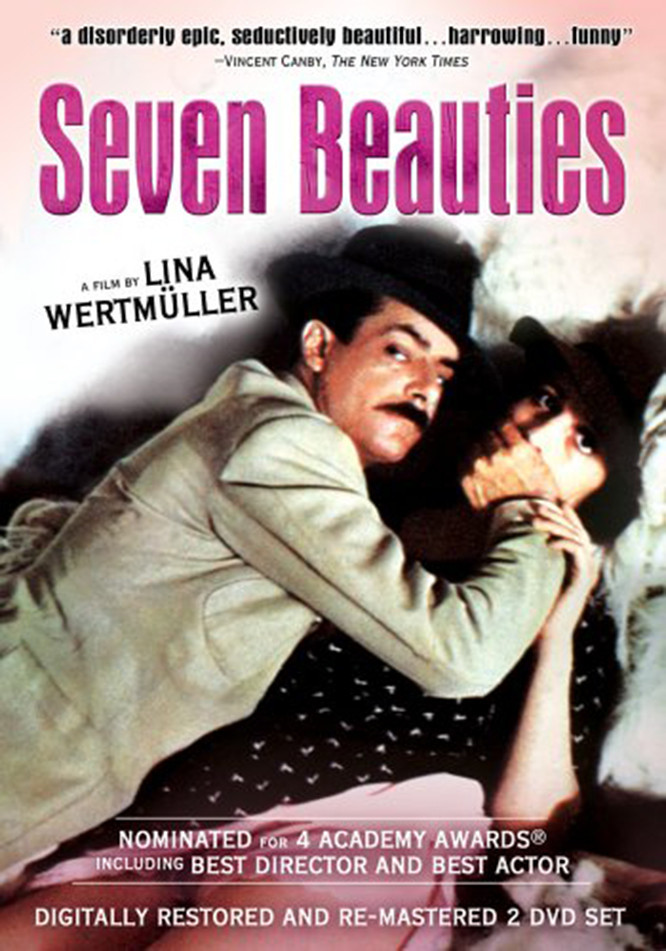

He kills the pimp. Then he dismembers the body, which is a very large one, and ships it to various Italian cities in bulky suitcases. He is brought to trial, found insane and sent to an asylum. On his way, he meets a fellow prisoner. He boasts of himself: “The ax-murderer. The Monster of Naples.” Any status is welcome. He spends a great deal of time admiring himself in the mirror and striking dashing poses. He’s eventually released from the asylum in order to serve in the Italian army, and it’s in this material that the movie takes its weird and unexpected turn. The prewar material seems vaguely related to Wertmuller’s “The Seduction of Mimi,” in which the hypocrisy of the Italian male sexual code is cheerfully ridiculed. But “Seven Beauties,” despite some very funny scenes, is not a cheerful movie. It’s a dark, brooding piece about the ways people are willing to debase themselves, and Pasqualino, for all of his honor, is a worm. He finds himself in a Nazi concentration camp. The commandant is a very large, plain, forbidding woman. She carries a whip as if it were her handbag.

Pasqualino recalls the advice of his mother, that even the most inaccessible woman can be reached through her heart, and he mounts a romantic campaign against the commandant. She isn’t deceived for a moment by his lies, but she does use him, and in the scenes of their coupling Wertmuller provides some of the most disturbing images she’s ever filmed. Many of her films see relationships between men and women as elaborations of sadomasochistic themes, but “Seven Beauties” has the darkest and most despairing of her couples. After Pasqualino successfully makes love to the commandant – in what’s easily the least erotic sex scene ever filmed – she sets out to destroy his character, if any. He’s forced to select six fellow prisoners for extermination, and later, to put a bullet through the head of his best friend. He does. He suffers as he does so, perhaps, but not as much as he did at the slights to his sister’s honor, or over missed, meals. “Seven Beauties” isn’t the account of a man’s fall from dignity, because Pasqualino never had any – and that’s what makes it intriguing.

Why did Wertmuller make it? To explore banality and cruelty? To give us a vision of the Nazi experience in which moral choices are irrelevant and the characters join together in a grim mutual debasement? To make, as an exercise, an ultimate black comedy? I can’t say. I’m not sure there is a rational answer; the movie seems to be a working out on a subconscious level of behavior patterns Miss Wertmuller finds both fascinating and inexplicable.

So the movie’s absorbing and mysterious. It doesn’t explain itself. It presents its funny scenes – Giancarlo Giannini preening himself in the mirror of his own mind, and then unwittingly behaving as a total fool – with the same detachment it uses in scenes of total pessimism. Its virtuoso style, demonstrating once again Miss Wertmuller’s mastery of filmmaking, is used to tell us a story that’s very opaque, despairing, and bottomless.