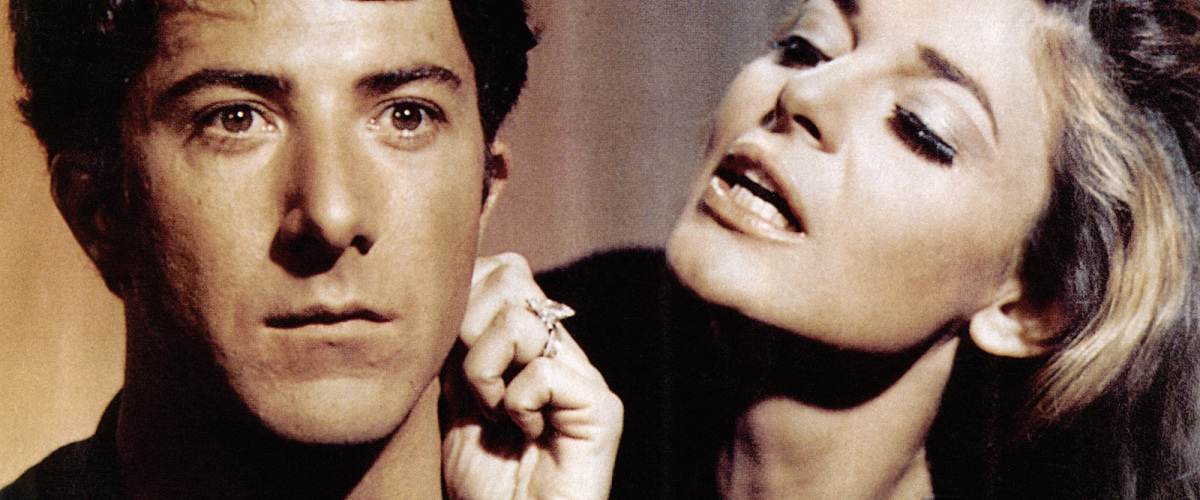

Well, here *is* to you, Mrs. Robinson: You’ve survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in “The Graduate.” How could I ever have thought otherwise? What murky generational politics were distorting my view the first time I saw this film? Watching the 30th anniversary revival of “The Graduate” is like looking at photos of yourself at an old fraternity dance. You’re gawky and your hair is plastered down with Brylcreem, and your date looks as if you found her behind the counter at the Dairy Queen. But–who’s the babe in the corner? The great-looking brunette with the wide-set eyes and the full lips and the knockout figure? Hey, it’s the chaperone! Great movies remain themselves over the generations; they retain a serene sense of their own identity. Lesser movies are captives of their time. They get dated and lose their original focus and power. “The Graduate” (I can see clearly now) is a lesser movie. It comes out of a specific time in the late 1960s when parents stood for stodgy middle-class values, and “the kids” were joyous rebels at the cutting edge of the sexual and political revolutions. Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), the clueless hero of “The Graduate,” was swept in on that wave of feeling, even though it is clear today that he was utterly unaware of his generation and existed outside time and space (he seems most at home at the bottom of a swimming pool).

“The Graduate,” released in 1967, contains no flower children, no hippies, no dope, no rock music, no political manifestos and no danger. It is a movie about a tiresome bore and his well-meaning parents. The only character in the movie who is alive–who can see through situations, understand motives, and dare to seek her own happiness–is Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft). Seen today, “The Graduate” is a movie about a young man of limited interest, who gets a chance to sleep with the ranking babe in his neighborhood, and throws it away in order to marry her dorky daughter.

Consider, for a moment, the character of Elaine (Katharine Ross), Mrs. Robinson’s daughter. She has no dialogue of any depth. She has an alarming fetish for false eyelashes. She agrees to marry a tall, blond jock (Brian Avery) mostly because her parents will be furious with her if she doesn’t. She is so witless that she misunderstands everything Benjamin says to her. When she discovers Benjamin has slept with her mother, she is horrified, but before they have ever had a substantial conversation about the subject, she has forgiven him–apparently because Mrs. Robinson is so hateful that it couldn’t have been Benjamin’s fault. She then escapes from the altar at her own wedding to flee with Benjamin on a bus, where they look at each other nervously, perhaps because they are still to have a meaningful conversation.

As Benjamin and Elaine escaped in that bus at the end of “The Graduate,” I cheered, the first time I saw the movie. What was I thinking of? What did the scene celebrate? “Doing your own thing,” I suppose.

Occasionally I will meet an almost-adult son of friends, and notice that he behaves like a mute savage in company, responding to conversation with grunts and inarticulate syllables. This behavior is usually accompanied by uncoordinated lurches, as if he is behind the wheel of a body too big for him to drive. A few years pass, and this creature regains the use of his brain and speech, and I see that he was passing through a phase. Does he look back on his earlier years in embarrassment? Today, looking at “The Graduate,” I see Benjamin not as an admirable rebel, but as a self-centered creep whose put-downs of adults are tiresome. (Anyone with average intelligence should have known, in 1967, that the word “plastics” contained valuable advice–especially valuable for Benjamin, who lacks creative instincts and is destined to become a corporate drudge.) Mrs. Robinson is the only person in the movie who is not playing old tapes. She is bored by a drone of a husband, she drinks too much, she seduces Benjamin not out of lust but out of kindness or desperation. Makeup and lighting are used to make Anne Bancroft look older (she was 36 when the movie was made, and Hoffman was 30). But there is a scene where she is drenched in a rainstorm; we can see her face clearly and without artifice, and she is a great beauty. She is also sardonic, satirical and articulate–the only person in the movie you would want to have a conversation with.

When the movie was first released, I wrote of the “instantly forgettable” songs by Simon and Garfunkel. History has proven me wrong. They are not forgettable. But what are they telling us? The liberating power of rock and roll is shut out of the soundtrack (“The Sound of Music” plays on Muzak at one crucial point). The S&G songs are melodic, sophisticated, safe. They even accommodate the action, halting their lyrics and providing guitar chords to underline key moments. This is Benjamin’s music; Mrs. Robinson, alone with her vodka, would twist the radio dial looking for the Beatles or Chuck Berry.

Is “The Graduate” a bad movie? Not at all. It is a good topical movie whose time has passed, leaving it stranded in an earlier age. I give it three stars out of delight for the material it contains; to watch it today is like opening a time capsule. To know that the movie once spoke strongly to a generation is to understand how deep the generation gap ran during that extraordinary time in the late 1960s. There were true rebels in movies of the period (see “Easy Rider”), but Benjamin Braddock was not one of them. I wonder how long it took him to get into plastics.