Wandering in the rain, the man looks like one of the walking wounded. His talk is obsessive chatter, looping back on itself, seizing on words and finding nonsense associations for them. He laughs a lot and seems desperately affable. When he sits down at a piano in a crowded restaurant, he looks like trouble, until he starts to play. His music floods out like a cry of anguish and hope.

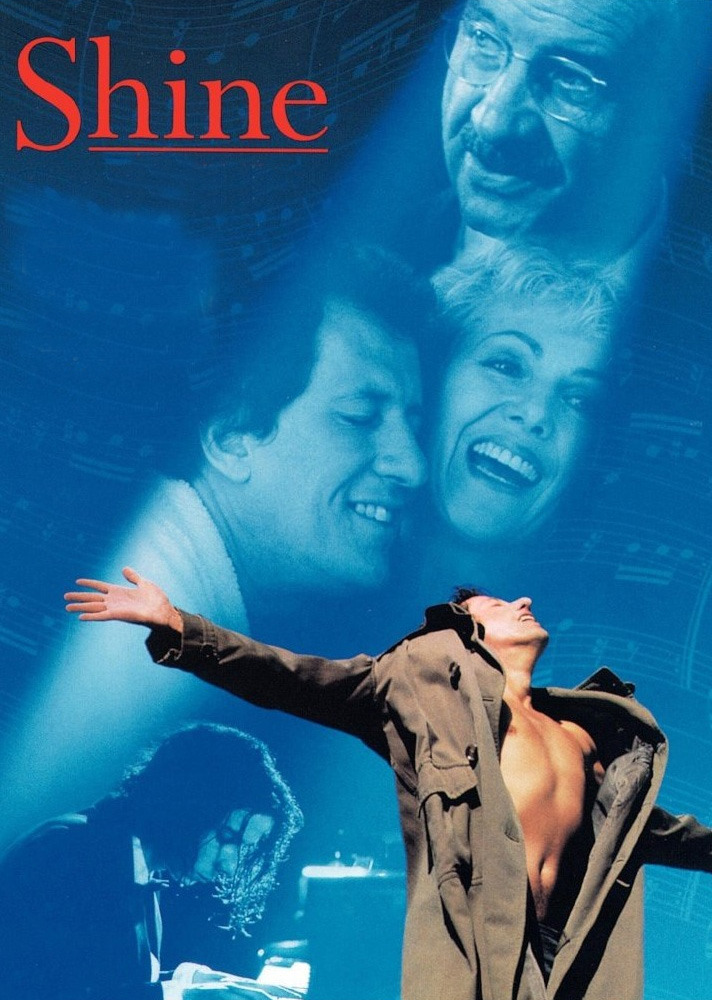

This is the central image in Scott Hicks‘ “Shine,” based on the true story of an Australian pianist who was an international prodigy, suffered a breakdown and has gradually been able to piece himself back together. The musician’s name is David Helfgott. His life story is not exactly as it is shown here, but close enough, I gather, for us to marvel at the way the human spirit can try to heal itself.

The movie circles in time, using three actors to play Helfgott. Alex Rafalowicz is young David, encouraged to excel at music and chess by a domineering father who slams the chessboard and shouts, “You must always win!” He is savage when his son places second in a national competition. Noah Taylor, so good in “Flirting,” plays the adolescent David, who blossoms at the piano, but is forbidden by his father to accept a scholarship offered by violin great Isaac Stern. Geoffrey Rush plays David as an adult who goes mad and then slowly heals with the help of an understanding woman.

But it is all so much more complicated than this makes it sound. We should begin with David’s father, Peter (Armin Mueller-Stahl), a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust but lost most of his family. Now resettled in Australia, he places family above everything; refusing to let David study at the Royal College of Music in London, he screams, “You will destroy your family!” Peter is capable of violence but also tenderness and love; his family is in the grip of his tyranny, and it is little wonder that David comes unglued, torn between his father’s demands that he be perfect at the piano, and his refusal to let him follow his musical career where it will lead.

David finds friendship and support from an old woman (Googie Withers), who encourages his music and helps him find the courage to go to London, where his tutor is played wonderfully, with dryness and affection, by John Gielgud. There he is happy for a time, but during a performance of the formidable Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3, David comes apart.

We see him next as a middle-aged man, a wanderer back in Australia, talking nonsense, his name forgotten by all but a few. (I understand that Scott Hicks got the idea for this film when he came across Helfgott playing in a restaurant and heard his story.) One of the buried motifs of “Shine” is the war that goes on between David’s parent-figures. His father is a monster and his mother is weak, but the old woman in Perth helps him, and so does a piano teacher (Nicholas Bell). His key helper is a middle-aged astrologer (Lynn Redgrave), who meets him through a friend, toward the end of his restaurant days. They fall in love, and love saves him.

Music is one of the areas in which child prodigies often excel; two others are mathematics and chess. All three have the advantage of not requiring much knowledge of life or human nature (for technical proficiency, anyway). David’s piano playing is at first a skill that comes naturally to him; only later does it become an art, a way of self-expression.

What is terrifying for him is that the better he gets, the closer he comes to expressing feelings that his father has charged with enormous guilt. The “Rach 3” is a tumult of emotion, and what happens is that David cannot perform it without being destroyed by the feelings it releases.

The father is undergoing a process similar to the one he has inflicted on his son. He too cannot deal with the emotions unleashed by his son’s playing, which is why he forbids David to study in Europe; if the son becomes good enough, he will fly away on the wings of the music, breaking up the sacred family unit and reopening the father to all the terrors of the Holocaust–terrors against which he has risen up as a bulwark to his family in its little suburban house. The last scene of the movie (filmed, I have been told, at Peter Helfgott’s actual grave) tries to acknowledge some of these truths: Peter is a man whose life inflicted great damage, not least upon himself.

There has been much talk in 1996 about films whose filmmakers claim they were based on true stories but were kidding (“Fargo”), and films whose filmmakers claimed they were based on true stories but might have been lying (“Sleepers”). Here is a movie that is based on the truth beneath a true story.

The fact that David Helfgott lived the outlines of these events–that he triumphed, that he fell, that he came slowly back–adds an enormous weight of meaning to the film. I understood Helfgott is preparing a concert tour of North America. Anyone who has seen this movie will want to hear him–not for the “comeback drama,” so much as to hear the music he kept playing during his years in the wilderness, and which led him back again to his true calling.