Oliver Stone creates empathy for this most enigmatic of American leaders. One of the year’s best films.

Oliver Stone’s “Nixon” gives us a brooding, brilliant, tortured man, sinking into the gloom of a White House under siege, haunted by the ghosts of his past. Thoughts of Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear come to mind; here, again, is a ruler destroyed by his fatal flaws.

There’s something almost majestic about the process: As Nixon goes down in this film, there is no gloating, but a watery sigh, as of a great ship sinking.

The movie does not apologize for Nixon, and holds him accountable for the disgrace he brought to the presidency. But it is not without compassion for this devious and complex man, and I felt a certain empathy: There, but for the grace of God, go we. I rather expected Stone, the maker of “JFK” and “Natural Born Killers,” to adopt a scorched-earth policy toward Nixon, but instead he blames not only Nixon’s own character flaws but also the Imperial Presidency itself, the system that, once set in motion, behaves with a mindlessness of its own.

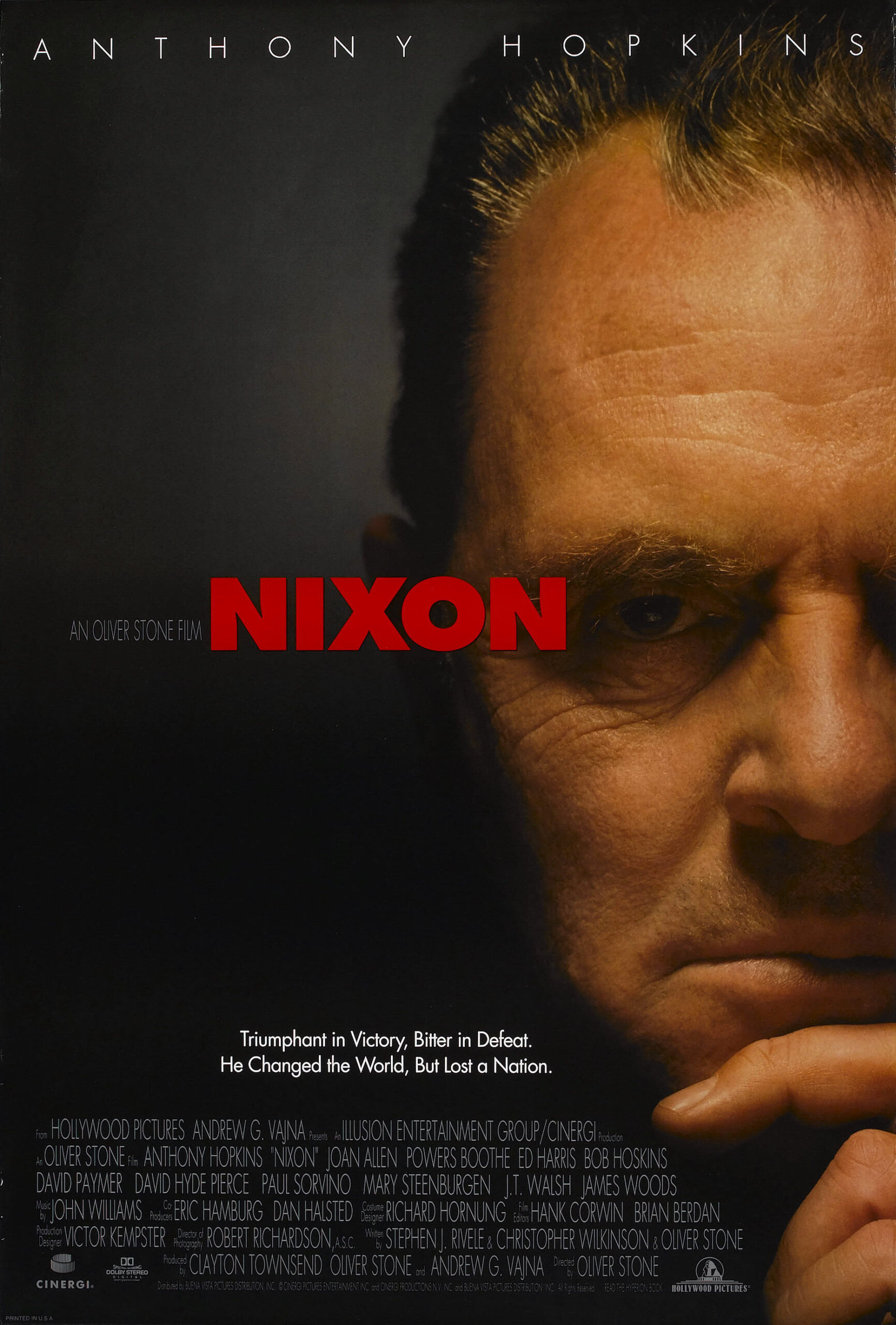

In the title role, Anthony Hopkins looks and sounds only generally like the 37th president. This is not an impersonation; Hopkins gives us a deep, resonant performance that creates a man instead of imitating an image. Stone uses the same approach, reining in his stylistic exuberance and yet giving himself the freedom to use flashbacks, newsreels, broadcast voices, montage and the device of clouds swiftly fleeing over the White House sky as events run ahead of the president’s ability to control them.

“Nixon” is flavored by the greatest biography in American film history, “Citizen Kane.” There are several quotes, such as the opening upward pan from outside the White House fence, the gothic music on a cloudy night, the “March of Time”-style newsreel, and the scene where the president and Mrs. Nixon sit separated by a long dinner table. The key device that Stone has borrowed is the notion of “Rosebud,” the missing piece of information that might explain a man’s life.

In Stone’s view, the infamous 18 1/2-minute gap on the White House tapes symbolizes a dark hole inside the president’s soul, a secret that Nixon hints at but never reveals. What is implied is that somehow a secret CIA operation against Cuba, started with Nixon’s knowledge during the last years of the Eisenhower administration, turned on itself and somehow led to the assassination of John F.

Kennedy.

The movie doesn’t suggest that Nixon ordered or desired Kennedy’s death, but that he half-understood the process by which the “Beast,” as he called the secret government apparatus, led to the assassination. Learning that former CIA Cuba conspirator E. Howard Hunt was involved in the Watergate caper, he murmurs, “He’s the darkness reaching out for the dark. Open up that scab, you uncover a lot of pus.” And in an unguarded moment, he confides to an aide, “Whoever killed Kennedy came from this thing we created – this Beast.” If the 18 1/2-minute gap conceals Rosebud, it is like the Rosebud in “Kane,” explaining nothing, but pointing to a painful hole in the hero’s psyche, created in childhood. “Nixon” shows the president’s awkward, unhappy early years, as two brothers die, and his strict Quaker parents fill him with a sense of purpose and inadequacy. “When you quit struggling, they’ve beaten you,” his father says. And his mother (Mary Steenburgen), speaking in the Quaker tradition of thees and thous, seems always to hold him to a higher standard than he can hope to reach.

Stone, who was burned by accusations that some of the history in “JFK” was fabricated, opens with the disclaimer that some scenes are based on hypothesis and speculation. Many of the scenes, in fact, come out of our memory book of Nixon’s greatest hits: the Checkers speech, “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore”; the summit with Mao; the bizarre midnight visit with anti-war protesters at the Lincoln Memorial, and the strange scene, reported in Woodward and Bernstein’s The Final Days, in which a crushed president asks Henry Kissinger to join him on his knees in prayer.

One theme throughout the film is Nixon’s envy of John F. Kennedy. He judges his entire life in terms of his nemesis. Nixon on JFK’s 1960 campaign: “All my life he’s been sticking it to me. Now he steals from me.” Nixon, bitter at not being invited by Kennedy’s family to JFK’s funeral, reflecting half-enviously: “If I’d been president, they never would have killed me.” Nixon, alone at the end, speaking to the portrait of JFK: “When they look at you, they see what they want to be. When they look at me, they see what they are.” Stone has surrounded his Nixon with a gallery of figures we remember from the Watergate years, played by actors of a uniformly high caliber. Bob Hoskins creates a feral, poisonous J. Edgar Hoover, eating melon from the mouth of a handsome pool boy and ogling the Marine guards at a White House reception. Paul Sorvino plays Kissinger, reserved, watchful, disbelieving as he gets down on his knees to pray. J. T. Walsh and James Woods are Ehrlichman and Haldeman, the inner guard, carefully monitoring the nuances between what is said and what is implied. Powers Boothe is the impeccable Alexander Haig, who firmly guides the president toward resignation.

When Nixon ponders a cover-up of the tapes, it is Haig who raises the (imaginary?) possibility that backup copies might surface. Notice the precision of his wording: “I know for a fact that it’s possible that there was another tape.” The key supporting performance in the movie, however, is by Joan Allen as Pat Nixon. She emerges as strong-willed and clear-eyed, a truth-teller who sees through Nixon’s masks and evasions. She is sick of being a politician’s wife. Their daughters, she says, know Nixon only from television. More than anyone else in the film, she supplies the conscience.

“Nixon” would be a great film even if there had been no Richard Nixon. In its control of mood and personality, in the way the president musters moments of brilliance even as the circle closes, in the way it shows advisers huddled terrified in the corridors of power, it takes on the resonance of classic tragedy. Tragedy requires the fall of a hero, and one of the achievements of “Nixon” is to show that greatness was within his reach.

Aristotle advises that the listener to a tragic tale will “thrill with horror and melt with pity.” Yes, and so we do, because Nixon was right about his life: The cards were stacked against him, even though he dealt most of them himself.