Gallaudet University is only university in the United States that serves a Deaf student population. It was founded in 1864 after an order by then-president Abraham Lincoln, and is supported by 75% federal funds, but for the first 124 years of its existence, it never had a Deaf president, only hearing presidents appointed by a board of trustees composed mostly or entirely of hearing people. It wasn’t until 1988, when the board appointed yet another non-Deaf president, that the university’s students decided they’d had enough of being patronized. They rejected the incoming president, Elisabeth Zinser—a respected administrator who had a background in nursing before getting into academia, and had been the first female president of the University of Idaho, but wasn’t what the students felt they needed in order to feel truly understood and represented,

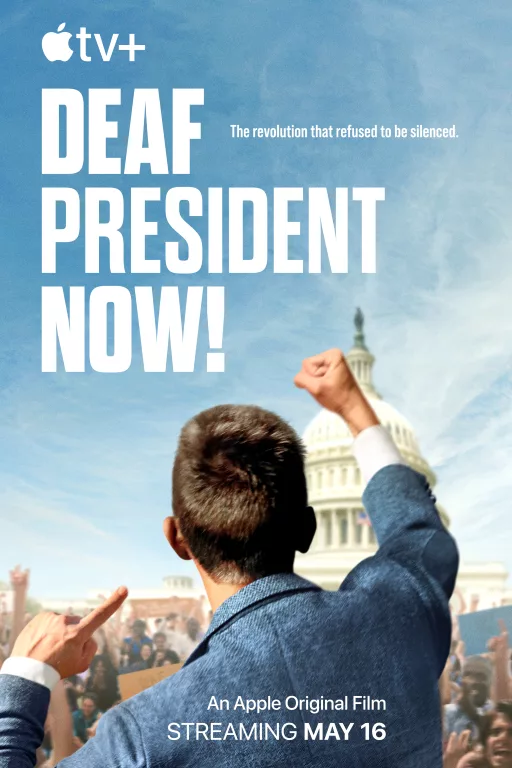

The resulting standoff between students and administrators is chronicled in “Deaf President Now!”, a joint effort by two filmmakers, Davis Guggenheim, who directed the Oscar-winning “An Inconvenient Truth”, and Nylie DeMarco, who gained fame as the first Deaf contestant to win “America’s Next Top Model” and “Dancing with the Stars” back-to-back, and is also a bestselling memoirist and movie producer. The result is as smartly conceived and constructed as it is thrilling to watch, and as passionate as it is informative. More significantly, it’s a stealthy formal triumph that refines existing cinematic language and adds brand new words and phrases to the vocabulary, as it were, because that’s what was needed to do justice to its subject matter.

The four main characters are student activists who moved into the media spotlight during a tumultuous week in which Gallaudet locked down the campus and refused to admit any non-student until Zinser withdrew her candidacy and a Deaf president was appointed in her place. There’s Jerry, who’s passionate, eloquent and stingingly funny but a bit of a loose cannon, and so demonstrative that at one point the camera has to tilt up to catch his signing because he’s gotten so excited that his hands have risen above the uppermost frameline. There’s Greg, who’s also quite animated and persuasive but more measured, and more of a big-picture thinker. There’s Bridgetta, an intrepid and seemingly fearless student who is also the only woman in the group, and consequently finds herself representing the female perspective on events because the men, for all their idealism, can be obliviously sexist at times. She’s also a former high school cheerleader who helps refine the group’s communication by coming up with group chants, reasoning that “what we needed was rhythm to keep everyone on the same beat.”

Finally, there’s Tim, who is so reticent and even-tempered that the other three worry he doesn’t know how to come on strong even when a moment demands it. As often happens in these types of situations, the least threatening person on the frontlines of publicity ends up becoming the consensus choice to represent the resistance in public-facing events and in negotiations with power. That ends up being Tim, who is well-liked by the other four, and a conciliatory—or you might prefer to say nonthreatening—presence in press interviews and public appearances, but not as exciting as the other (particularly the grandiloquent Jerry, described by Greg as someone who “[punches] against the wall instead of finding the key to open the door”). When the filmmakers ask the other three to describe Tim as a leader, they have to pause for a while to gather their thoughts and words, seemingly for fear of reflexively blurting out something negative. A lot of time has passed and all is forgiven now, but it’s clear that they weren’t happy with Tim’s selection in the early stages of his leadership (although he grew into the role).

The students repeatedly refuse the administration’s orders to stop the protest, open the campus, and accept their president or face police intervention. The pressure on them to back down keeps building. But the four main leaders and the student body they represent dig in their heels and repeat their demands that a Deaf president be appointed. As they say, it’s both the right and sensible thing to do, and it’s nonsensical to have gone more than a century-and-a-quarter being treated as helpless people to be protected from the hard reality of a hearing world when they’re already existing in it.

The face of authority here is not Zisman, a well-meaning woman who wasn’t raised in a culture in which minorities want and expect minority representation. Rather, it’s Jane Bassett Spilman, the chairman of the university’s board of trustees. Spilman is one of those authority figures who radiates entitlement and seems unaware of how a poor choice of words can insult the same folks that she’s supposed to be looking out for. Speaking in front an auditorium of justifiably pissed-off students early in the story, she stops just short of declaring that resistance is futile. There are also reports that Spilman once stated, “Deaf people are not ready to function in a hearing world,” which is obviously untrue, since the whole student body has been functioning in a hearing world throughout their lives. She eventually denies saying that, but her denial is unconvincing, to say the least. When the students roar their disapproval, she prissily complains “it’s very difficult to talk above this loud noise.” (Yikes!) Jerry calls her “the epitome of snobbery and wealth.”

Many movies about the hearing impaired are conceived in a way that seems focused on how to present a story with Deaf central characters for the enlightenment of viewers who are not hearing impaired. Perhaps the most famous example is the movie adaptation of the stage play “Children of a Lesser God,” wherein the hearing half of a hearing/Deaf couple verbally speaks every word that both characters say to each other, even though they both speak fluent ASL, and even when it’s just the two of them alone in a room. “Deaf President Now!” doesn’t do that. Instead, it relies on subtitles and verbal translation-as-narration, with some smart overlaps of the witness’s lip movements and the narrator’s audible voice.

It also deploys appropriate filmmaking techniques to suggest to hearing people what it’s like to be Deaf, as both a physical and political experience. Sometimes the sound cuts out entirely, or you only hear the low-end vibrations in a sound, which is how a Deaf person would experience it. The selection of archival footage and the staging of dramatic re-enactments is also from the perspective of Deaf people first, everybody else second, effectively flipping the script on how movies have typically told stories in the almost-century that followed the first sync-sound feature film, “The Jazz Singer.” When a person who is important to this story, or simply to a moment in a Deaf person’s life, turns their back—as in a hearing-dominant public school classroom in the 1960s when a teacher turns around to write on the chalkboard and continues verbally speaking, not thinking about whether the only Deaf kid in the room can follow the lesson.

I didn’t know the story of the 1988 Gallaudet University takeover, and a perusal of various present day accounts of great moments in the history of the disabled suggests that it’s been somewhat memory-holed. Co-director DiMarco said in an interview with Out that he “went to a regular public school, and I was talking to some of my hearing peers, and none of them knew about the Deaf history that I knew about,” he says. “And they were learning about all the different types of civil rights movements, except for Deaf President Now. They weren’t talking about this Deaf revolution that actually helped lead to the passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act.”

It shouldn’t be obscure after this movie, a knockout piece of work that justifiably keeps the focus on the deaf audience but is told in a way that mostly makes it easy for hearing people to follow everything, but that has little bracketed moments where a hearing person is necessarily going to feel left out, not from thoughtlessness, but rather to foster understanding and empathy, by making hearing viewers understand what it’s like to exist in a culture that rarely takes your particular needs or challenges into account even in what’s supposedly a popular medium, the art form of the masses. Roger Ebert famously described cinema as a machine that generates empathy. This movie is that machine: a relentless engine fueled by idealism and craft.