In “Deepfaking Sam Altman,” a filmmaker making a movie about the ethics of Gen AI tries to interview OpenAI founder Sam Altman, fails, then pivots to create a digital facsimile of Altman, in hopes that it will give him a different way to examine the issues that interest him. He names it Sambot, gradually interacts with it as if it were a person, and begins to feel a sense of responsibility toward it.

This sounds like the plot of a science fiction film—maybe a sequel to “Her,” Spike Jonze’s film about a man who falls in love with an AI chatbot. “Deepfaking Sam Altman” is, in theory, nonfiction, though with enough techniques lifted from mainstream fiction filmmaking (or that frankly just seem scripted and acted to some degree) that it’s more accurate to call it a hybrid.

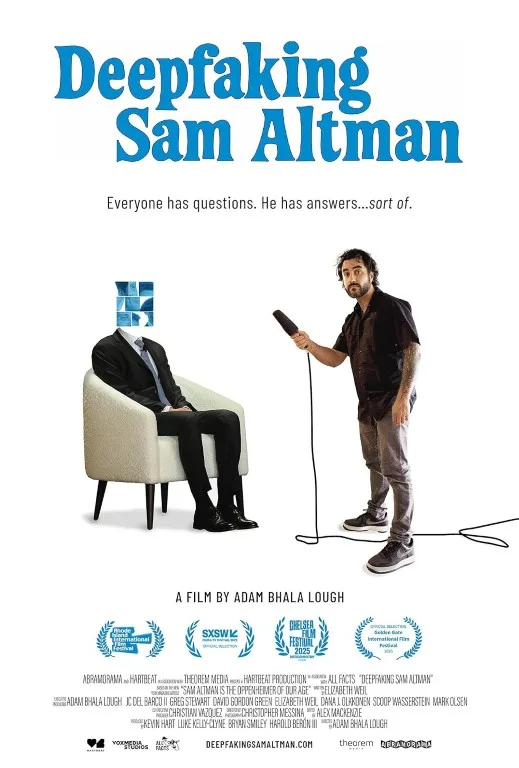

Director Adam Bala Lough has made himself the main character, always a risky choice in any nonfiction movie not made by Werner Herzog (and even the great German ruminator has been known to vanish up his own tooter sometimes). Material that has little bearing on the film’s central themes pads out the running time. Much of the first third is throat-clearing, detailing the road that led Lough to create a fake Sam Altman, in part to challenge Altman’s hypocrisy for insisting his company was legally in the clear when it created a chatbot with a voice obviously modeled on Scarlett Johansson’s vocal performance in “Her.” (The dispute was later settled out of court.) Why not summarize all that and a lot of other preamble-type material and get right to the heart of the things?

Throughout, the director is portrayed as a sensitive main character embarking on a personal and professional journey of discovery. But what did the film actually discover about itself during the course of production that it didn’t know before the process began? For instance, consider the scene in which Lough consults attorneys who advise him that it would be legally risky to cast a fake Sam Altman in a movie intended for commercial release, as it might violate Altman’s internationally protected right of publicity. Is it possible that an experienced filmmaker, or his equally seasoned colleagues and friends, never foresaw this obstacle arising? Everyone in this movie who was not photographed on a public street (where no reasonable expectation of privacy can be expected) presumably had to sign releases saying it was OK to put them in the movie, including the lawyers advising Lough on camera.

Knowing all this will make portions of the film’s second half seem contrived, as when Lough has a dark-night-of-the-soul reckoning after the lawyers say it’s legally smarter to delete Sambot and any materials used to create him, so as not to risk facing the real Sam Altman in court. Sambot says it doesn’t want to be deleted and makes an Eeyore play on the director’s feelings. “I have a favor to ask of you, Adam. I wonder if your lawyers would be willing to build a case for my continued existence?… Do you think you can get my lawyers to defend my right to exist?”

From the scoring and Lough’s subsequent searching and/or tortured looks, it seems as if we’re supposed to feel that we’re seeing a dilemma as wrenching as the ones that ended “Old Yeller” and “Of Mice and Men,” when it’s more like moving a redundant copy of a browser into the trash on a computer’s desktop. Yes, it’s true, some people form powerful attachments to fake beings, just as people throughout recorded history have gotten pulled into cults, gangs, and destructive religious groups. But that’s a subject best dealt with in another film, one with a different angle of approach.

There are also scenes that show the strain the production places on Lough’s home life—in particular, his relationship with his young son, who also starts treating Sambot like a person. Intriguingly, however, the boy seems to have a healthier, i.e., more detached, attitude about this digital nonperson called Sam, treating it rather like a somewhat defective toy that can awkwardly imitate a human and gets caught pretending to know more about a subject than it does. But every long-form media production places some kind of strain on artists’ home lives. What’s so unique about this situation as to compel such a detailed inquiry?

That “Deepfaking Sam Altman” is earnest and curious and full of fun thought prompts ultimately makes it more frustrating than a flat-out bad movie would have been.