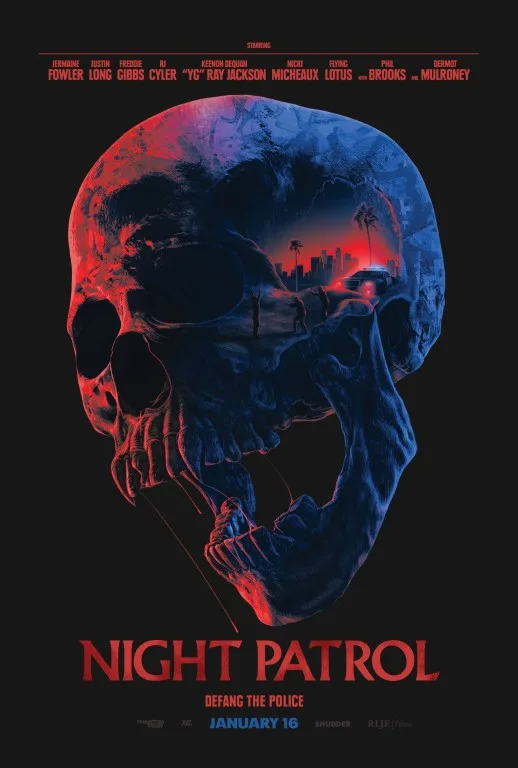

Writer-director Ryan Prows‘ “Night Patrol,” a cop corruption thriller that’s also a vampire movie, has a sprawling cast, but focuses on four characters. There’s Ethan Hawkins (Justin Long), the son of a legendary LAPD cop (Dermot Mulroney), who wants to join The Night Patrol, an unofficial, secretive, elite unit within the department that’s essentially a vampire street gang with badges and uniforms. Ethan’s partner, Xavier Carr (Jermaine Fowler), is a Black patrolman who used to be a member of the Crips gang and hopes to rise up through the department’s ranks. Xavier’s brother, Wazi Carr (RJ Cyler), is a Crips-affiliated petty criminal who sleeps on a mattress on the floor of a small room at his mama’s house. He’s in shock over secretly witnessing an LAPD officer murdering someone close to him, and fears that a Night Patrol member will find and kill him to prevent him from testifying about what he saw.

Finally, there’s Xavier and Wazi’s mama, Ayanda Carr (Nicki Micheaux), the former wife of a long-dead revolutionary who has kept a rebellious flame burning in her heart for decades. Ayada is also a mystic, a local historian of sorts, and an aficionado of supernatural lore who’s plugged into a network of anti-authoritarians (some criminals, some not) that find and kill monsters posing as powerful humans to gain access to fresh converts and, uh, meals.

Any disgruntled Marxist who’s ever used the phrase “capitalist bloodsuckers” will feel seen by this film, in which bloodsucking is both metaphorical and literal. One of its organizing premises is that police look out for themselves first, society’s power brokers second, and everyone else a distant third.

A different narrative rebuts that cynical view: police are self-sacrificing warriors protecting law-abiding citizens against criminality. Or, as Hawkins’ cop father insists, the police are here to reinforce “the fine line between civilization and the unwashed.” This is the same formulation that led to the creation, in 2014, in response to police brutality protests in Ferguson, Missouri, of the “Thin Blue Line” flag, a US flag rendered in black and white with a blue line across the middle. Some have called not authoritarian and implicitly white-supremacist because Black represents “chaos and anarchy,” while white represents “the citizenry who stand for justice and order.” You can see the flags on lawns all over the United States.

All of which is another way of saying that the political framework of “Night Patrol,” which is tended and embellished throughout the movie’s running time, comes from life. Early in the story, Ethan tells a small group of students gathered in a high school gymnasium, “In the media and movies, we’re seen in a very specific light, often a negative light. And there are a few bad apples out there. But I’m here to tell you that most of us are good. We’re good apples.” At a time when the US Department of Justice has been weaponized against the president’s designated enemies, and ICE is invading US cities and brutalizing and kidnapping people without identifying themselves or presenting warrants, the “a few bad apples don’t spoil the barrel” defense is arguably less persuasive than ever.

“Night Patrol” doesn’t endorse notions of an egalitarian US in which everyone is equal under the law, presumably because viewers would find it ridiculous no matter who they voted for. In the gymnasium scene, the student who is most visibly disbelieving and annoyed is also the only Black student. The cop’s monologue is cut short when a gymnasium door bursts in, and a Black gunman with a kerchief covering the bottom half of his face enters, blasting an Uzi at the ceiling and threatening the audience, then demands the only Black student at the assembly kneel on the hardwood floor and suggestively suck his own finger. The masked gunman is subsequently revealed as Xavier having a bit of fun. Ethan warns Xavier that pulling a stunt like that could get him kicked off the force, and that using blanks, not live ammo, wouldn’t hold much weight with investigators, even though they’re both buzzed by the students’ terror at briefly becoming hostages.

We intuit that Xavier must carry a lot of self-loathing to pick on the only Black student in the gym. Sure enough, it turns out that Xavier’s family were Black Panther-affiliated progressive activists who made common cause with local gangs, including one (led by rapper Freddie Gibbs’ stony badass Cornelius) that purports to battle lizard men, demons, Satan, and other malevolent forces. Does Xavier’s abandonment of his old identity make him a “pick me” type whose obsequious identification with the LAPD makes him a traitor to his community? “What is that, the Crip version of rebelling against your parents?” teases Hawkins.

One of the most insightful aspects of the script (credited to Prows, Shaye Ogbonna, Tim Cairo, and Jake Gibson) is how it portrays the relationship between police and their communities. The Los Angeles citizens in this movie are treated like natives of a foreign land that’s under military occupation. The police here have no apparent connection to the people they’re supposed to serve and protect. Joining a police force, suggests “Night Patrol,” makes a person loyal to other police, whether they are engaged in necessary and lawful work or violating their oath, and inclined to view criticisms as painful, unfair attacks on their self-image as The Good Guys.

Sure enough, a lot of Ethan and Xavier’s bond comes from shared the dopamine hits that are built into big-city policing, whether they’re generated by chasing a suspect through an alley, pulling over an anonymous motorist who could be armed and dangerous; or availing themselves of the countless minor privileges that accrue after joining what criminal justice reporter Jessica Pishko calls the “Law Enforcement Baronial Class.” That last benefit is illustrated in a scene where Ethan and Xavier have lunch at a taco stand, and Ethan cheerfully speaks Spanish to the cook. They both receive their meals immediately, and neither party indicates that payment was ever expected.

Notice, too, how the violent or chaotic actions that Ethan and Xavier partake in have so little apparent impact on their psyches that they’re subsequently shown laughing at each other’s terrible jokes as if they’re just a couple of regular dudes hanging out. Whenever Hawkins or Carr seem to experience pangs of guilt, the moment passes quickly.

There is a sense in which both police officers’ life trajectories were locked in due to the family traumas and dysfunctions they endured as children. Ethan wants to live up to the image of his late father (Dermot Mulroney), a violent and domineering man of bulldozing moral certitude. Xavier hopes to set himself apart from his mother, who states that both he and Wazi disappointed her for different reasons, and makes it clear that what matters most to her in life is sticking it to The Man.

“Night Patrol” doesn’t feel as fleshed out as it should. There are a few affectations that are annoying because they don’t seem organically rooted in the story, such as the pointless numbered chapter titles, a residue of the post-“Pulp Fiction” years when every other director wanted to be Quentin Tarantino. The script spends its first two-thirds jumping among parallel narrative tracks while setting up a big finish in which everything converges in a hail of bullets. But when that final stretch arrives, it may be hard to muster excitement because, as skillfully staged as it is, we’ve seen a lot of large-scale action scenes with heavily armed characters battling in one location, but we haven’t seen anything quite like the mythology of the criminals and cops that’s fleshed out during the lead-up.

But it’s still invigorating to see a horror movie that has a lot on its mind and chooses to express it in the manner of ’70s-generated horror masters like George Romero, Wes Craven, and John Carpenter, who weren’t afraid to embed social critiques in tales of fantastic and terrifying creatures. Carpenter’s influence is especially palpable, thanks to Benjamin Kitten’s lusciously grainy wide-frame imagery; Pepijn Caudron’s buzzing, growling, thumping synthesized score; and Prows’ willingness to slow the pace to make room for character development and atmosphere for its own sake.

Most impressive of all is the feeling that these humans (and vampire folk) live in a world that existed long before we started watching the film that they’re in. All of the lead characters reveal more complexity than we might have expected, including ones that are coded as straight-up villains. Which is to say that “Night Patrol” is a of-the-moment political movie Trojan-horsed into theaters and onto streaming platforms that’s being sold as an edgy little escapist horror flick with nothing on its mind but fun. The movie would play equally well on a double bill with Kathryn Bigelow’s 1987 vampire movie “Near Dark,” in which the bad guys are a murderous sensuous, bloodsucking version of the Bonnie and Clyde gang, tantalizing a straight-arrow farm lad with promises of a decadent outlaw life; and “Training Day,” about a ring of crooks within the LAPD that’s little more than a street gang with qualified immunity.

“Night Patrol” is far from perfect, but it’s got a certain something that pulls you in. The bleakness of its worldview is matched by the integrity of its filmmaking and performances. The life it depicts is not sugarcoated. It’s drenched in blood.