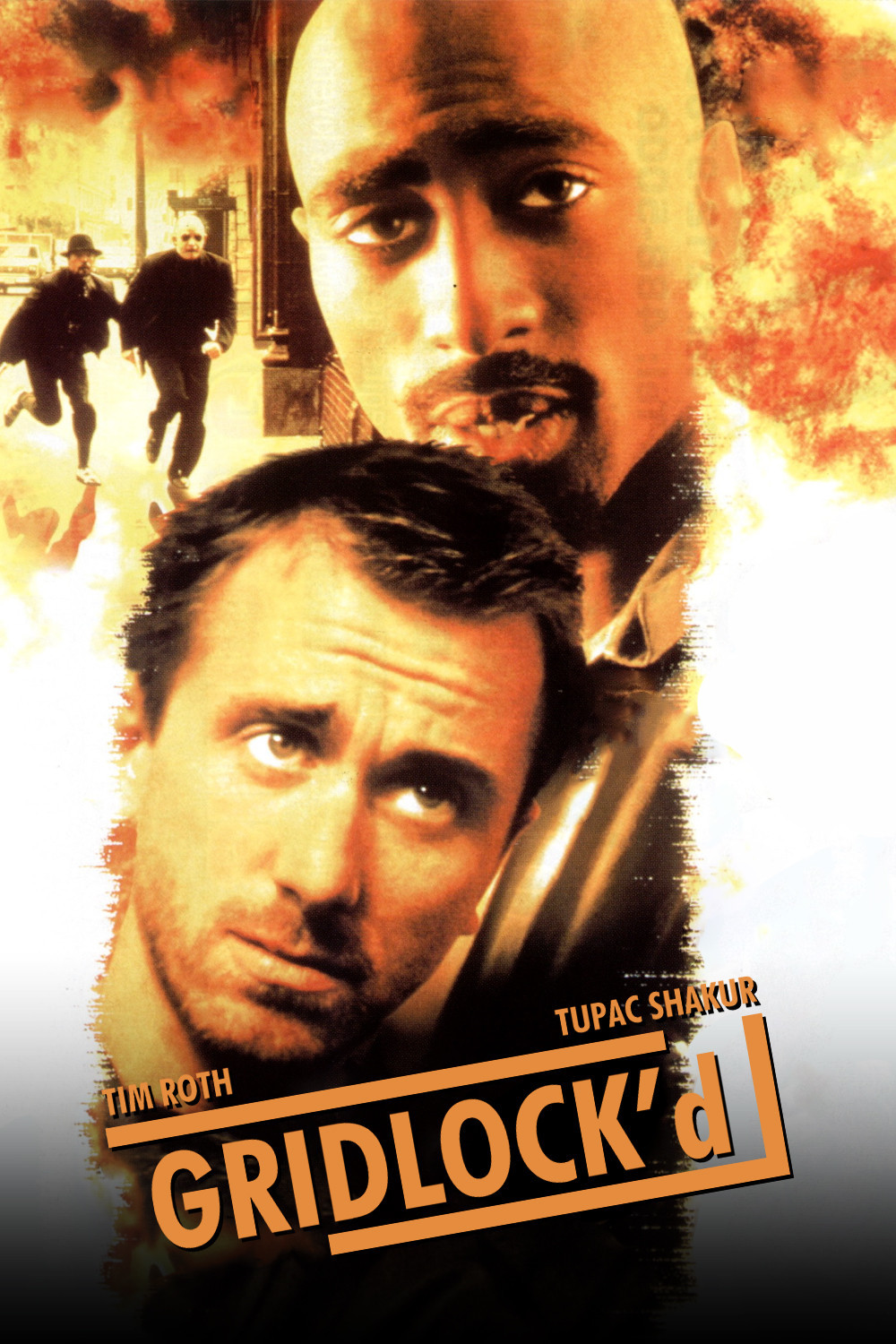

It is possible to imagine “Gridlock’d” as a movie of despair and desperation, but that would involve imagining it without Tupac Shakur and Tim Roth, who illuminate it with a gritty, goofy comic spirit. This is grim material, but surprisingly entertaining, and it is more cause to mourn the recent death of Shakur, who gives his best performance as Spoon, a musician who wants to get off drugs.

Spoon and his friend Stretch (Roth) arrive at this decision after rushing Spoon’s girlfriend Cookie (Thandie Newton) to an emergency room, comatose after a drug overdose. The three of them have a jazz trio. Ironically, she’s the clean liver, always eating veggieburgers and preaching against smoking. While Cookie hovers in critical condition, Spoon and Stretch spend a very long day trying to find a rehab program for themselves.

The heart of the movie is their banter, the grungy dialogue that puts an ironic spin on their anger and fear. Tim Roth is a natural actor, relaxed in his roles, with a kind of quixotic bemusement at life’s absurdities. Shakur, the hip-hop star turned actor, matches that and adds an earnestness: In their friendship, Spoon is the leader and thinker, and Stretch is the sidekick who will go along with whatever’s suggested. It’s Spoon who decides to kick, telling his friend (in a line that now has dark undertones), “Lately I feel like my luck’s been running out.” Writer-director Vondie Curtis Hall, making his directing debut after a TV acting career on “Chicago Hope” and other shows, combines the hard-edged, in-your-face realism of street life with a conventional story that depends on stock characters: evil drug dealers, modern Keystone Kops, colorful eccentrics. The movie isn’t as powerful as it could have been, but it’s probably more fun: This is basically a comedy, even if sometimes you ask yourself why you’re laughing.

That’s especially true in a scene that moviegoers will be quoting for years. Spoon, desperate to get into an emergency room and begin detox, persuades Stretch to stab him. As the two friends discuss how to do it (and try to remember which side of the body the liver is on), there are echoes of the overdose sequence in “Pulp Fiction.” What Tarantino demonstrated is that with the right dialogue and actors, you can make anything funny.

The daylong duel with the drug dealers and the encounters with suspicious cops work like comic punctuation. In between is the real life of the movie: the friendship of the two men and their quest to get into rehab. They circle endlessly through a series of Detroit social-welfare agencies that could have been designed by Kafka: They find they can’t get medicards without being on welfare, can’t get into detox without filling out forms and waiting 10 days, can’t get into a rehab center because it’s for alkies only, can’t get the right forms because an office has moved, can’t turn in the forms because an office is about to close. If this movie reflects real life in Detroit, it’s as if the city deliberately plots to keep addicts away from help.

In movies about stupid bureaucracies, the heroes inevitably blow up and start screaming at the functionaries behind the counters. Hall’s script wickedly turns the tables: The clerks shout at Spoon and Stretch. Elizabeth Pena plays an ER nurse who maddeningly makes them fill out forms while Cookie seems to be dying. When Spoon screams at her, she screams back in a monologue that expresses all of her exhaustion and frustration. Later, at a welfare center, an overworked clerk shouts back: “Yeah, we all been waiting for the day you come through that door and tell us you’re ready not to be a drug fiend. After five, 10 years, you decide this is the day, and the world stops for you?” This material is so good, I wish we’d had more of it. Maybe Hall, aiming for a wider audience, hedged his bets by putting in scenes where the heroes, the drug dealers and the cops chase one another on foot and in cars around downtown Detroit. Those scenes aren’t plausible and they’re not about anything.

Much better are the moments when the two friends sit, exhausted, under a mural of the great outdoors and talk about how they simply lack the energy to keep on using drugs. Or when Spoon remembers his first taste of cocaine in high school: “I didn’t even know what it was. Everybody else was throwin’ up. But for me it was like going to the moon.” Or when they watch daytime TV and do a running commentary. Or when they’re almost nabbed for a murder they didn’t commit.

Still, maybe Hall made the smart bet, by positioning this story halfway between real life and a crime comedy. The world of these streets and tenements and hospitals and alleys is strung out and despairing, and the human comedy redeems it. By the time a guy is trying to help his friend by stabbing him, we understand well enough what drugs will lead you to. For its premiere audience at the Sundance Film Festival, “Gridlock’d” played like a comedy, with big laughter. Too bad Tupac couldn’t be there.