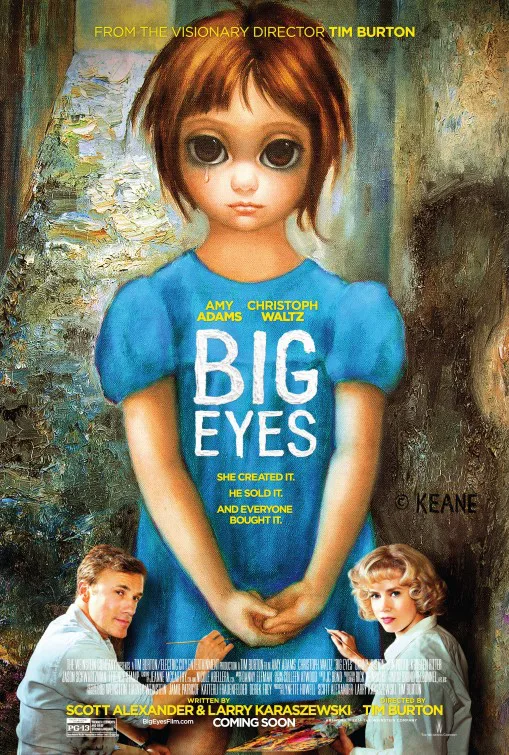

In Woody Allen’s “Sleeper,” a hip party-goer 200 years in the future presents a print of a big-eyed waif child to hostess Luna (Diane Keaton), and Luna breathes in awe, as though it was an original Gaugain: “Oh, it’s Keane! It’s pure Keane!” The joke is that the only art that will have any staying power in the future will be the work of Margaret Keane. In fact, it will increase in value. Hugely popular in the 1960s and 1970s (and still), Keane’s work inspired critical revulsion from an art world who found her popularity baffling and disheartening. However, Andy Warhol said, “I think what Keane has done is terrific! If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.” (He posed in front of a Keane print for photographer Steve Schapiro, mimkicking the child’s waif-like pose.) Margaret Keane allowed her husband, Walter, to take credit for her work for a good period of time in the 1960s, and that is the strange story of Tim Burton‘s latest film, “Big Eyes.” Entertaining in spots, obvious and irritating in others, with a one-note schticky performance from Christoph Waltz as Walter, “Big Eyes” is a strangely conventional entry in Tim Burton’s filmography. The story itself is fascinating, though, which helps, and Amy Adams’ quiet meticulous performance as Margaret Keane is a beautiful and emotional piece of work.

Margaret is first seen piling her young daughter and a couple of suitcases into a gigantic tail-finned car, and driving to San Francisco, fleeing from her marriage, determined to start a new life. Margaret then meets Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz) at an outdoor art fair, and he flatters her, gives her pep talks, and, before she even knows what is happening, they are going on a date, then another date, and then getting married. Margaret paints children with huge distorted eyes, and Walter paints Parisian street scenes (he lived on the West Bank for a while, he tells her); neither of them fit in with the trends in bohemian modern-art-obsessed 1960s San Francisco. Galleries scorn their work.

Walter is a big talker and a born promoter. He convinces the owner of a local jazz club to allow the two of them to hang their paintings along the hallway towards the rest rooms. One night, someone expresses admiration for one of the big-eyed paintings, and Walter, standing right there, takes credit for the work, hoping it will lead to a sale. The moment seems harmless at first, perhaps a misunderstanding, but then, as Margaret’s work starts to take off (and his is totally ignored), it happens again. Walter tells his wife that nobody would be interested in buying stuff from “lady painters,” and besides, she’s not good at talking about her own work or trying to sell it, and also, what does it matter if people think he painted it, as long as the two of them keep making money? Margaret is the type of person who is brow-beaten and intimidated by such logical arguments. She agrees to perpetuate the fraud, although it makes her uneasy and unhappy.

Walter Keane relishes his role as famous artist. He goes on talk shows, He opens his own gallery. He hustles his way into events. He comes up with a cockamamie story about how he spent time in Europe after the war, and was haunted by the devastation, by all the orphans. The orphans of the world are his inspiration for the big-eyed children he paints. Meanwhile, Margaret sits hunched in her artist’s garret, smoking, churning out the work that has made their fortune, unable to bask in her own glory. Margaret Keane would never have promoted herself into a world-wide phenomenon. She needed Walter for that.

Burton films all of this respectfully, with no fuss or fanfare, and except for one hallucinatory sequence in a grocery store when every customer stares mournfully at Margaret with hugely exaggerated eyes, the director plays it straight. There is an intermittent voiceover, given by a gossip columnist who was interested in Walter Keane; the voiceover helpfully (and simplistically) explains that “women didn’t just leave their husbands in those days.”

Christopher Waltz has been excellent in many films, with a knack for portraying ambition mixed with a smilingly callous approach to getting what he wants. With Walter Keane, Waltz telegraphs to us from the first moment we meet the character: “I am an unscrupulous individual. I am very sketchy. I am up to no good.” Waltz can’t resist “playing the villain”, doing so with such relish that he has nowhere to go but into caricature. The performance ratchets up and up and up, until finally he is a complete maniac, culminating in a scene where he tries to burn his house down, with his wife still in it. Waltz is obviously enjoying himself very much in the role, but maybe too much.

There’s a feminist undercurrent to “Big Eyes,” a sense that someone like Margaret Keane didn’t have the language to even understand how dominated by men she was, how much she enforced her own helplessness. When Walter tells her that art by women just doesn’t sell as well, Margaret doesn’t like it, but she acquiesces. She thinks he’s probably right. And he is right. She is in a very lonely position, shutting out her friends, her daughter. Walter has become her only conduit to the outer world.

Scrrenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who also wrote “Ed Wood,” “The People vs. Larry Flynt,” and “Man on the Moon“, are clearly interested in popular art—art that is perhaps scorned by the mainstream establishment, but still speaks to a broad and diverse group of people. Margaret Keane’s work was hated by the insiders of the art world; they hated Walter Keane’s hard-liner promotional tactics; they hated that paintings lacking their stamp of approval were selling like hot-cakes. This attitude is personified in the film by Jason Schwartzman’s snobby San Francisco gallery owner and influential art critic John Canaday (played by Terence Stamp), who described the big-eyed waifs as “atrocities.” Tim Burton, and his screenwriters, have a lot of affection for Margaret Keane’s work, they seem to take Andy Warhol’s position (Warhol’s quote opens the film). It’s an interesting question: who gets to say what is and is not art? Should popularity be equalled with bad? “Big Eyes” has a lot of fun with the established art world’s reaction to the big-eyes. When Schwarzman’s character, who despised the big-eyes, learns of Walter Keane’s fraud, he murmurs to himself, “Who would want to take credit?”

“Big Eyes” is full of fascinating questions about the meaning of art, the concept of popularity, and what it means to develop a huge audience. Back to Warhol: whether or not something is seen as “good” by an expert is irrelevant if so many people like it. The cultural gatekeepers will always be apoplectic in such a situation. “Big Eyes” is not a major film from Tim Burton, and it has some tonal issues, but one can see why he was drawn to such material. In a way, it’s a very personal film.