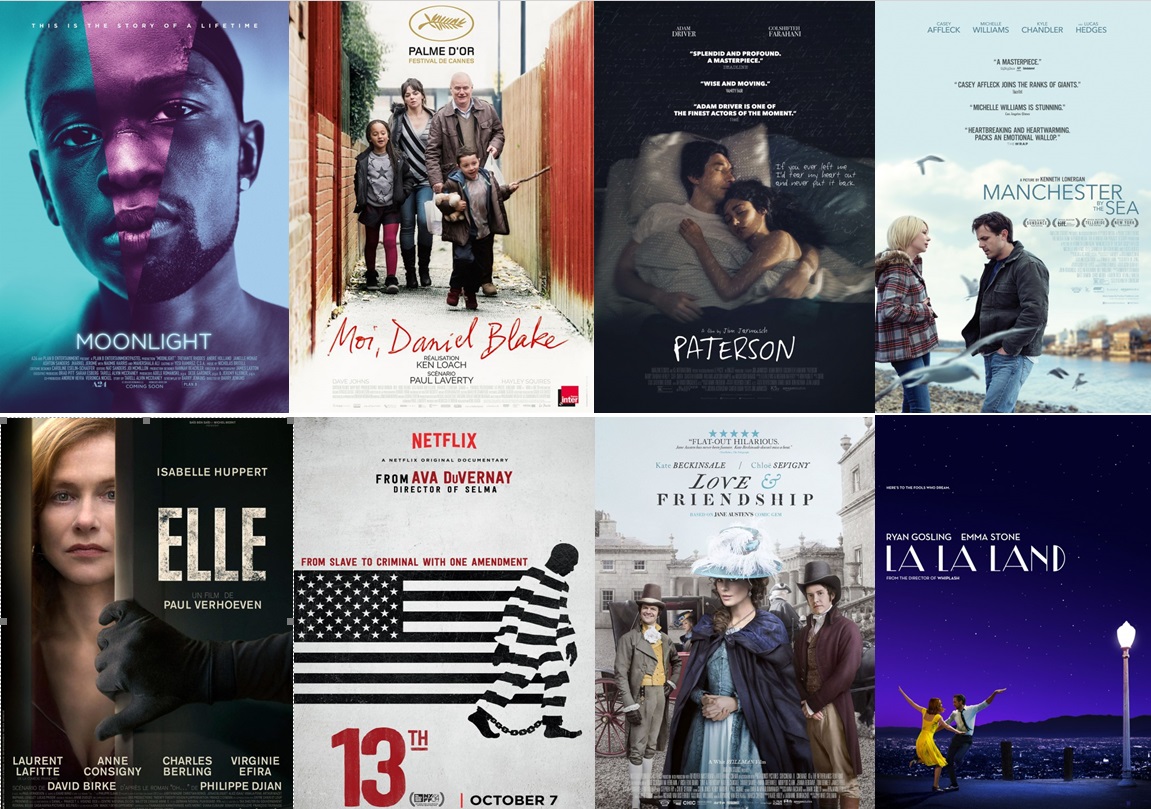

A year that will largely be defined by political differences and a shocking array of celebrity deaths also produced a remarkable number of high quality films. The diversity in our staff’s top ten lists, all of which will publish individually tomorrow, is indicative of the variety of films that caught our attention this year. And the movies that made the cut for our site top ten couldn’t be more unique from one another. What does Ava DuVernay’s latest documentary have in common with Kenneth Lonergan’s drama about grief? What cinematic DNA does Damien Chazelle’s hit musical share with Ken Loach’s issue-driven drama? While they may seem drastically different, their quality links them. Perhaps more than ever, we need different voices from around the world in our filmmaking. This top ten list indicates how much 2016 delivered on that front.

About the rankings: We asked our ten regular film critics and two assistant editors to submit top ten lists from this great year, and then consolidated them with a traditional points system—10 points for #1, 9 points for #2, etc.—resulting in the list below, with a new entry for each awarded film. We’ll publish all of our individual lists, along with many more by our regular contributors and some with detailed entries, tomorrow.

10. “I, Daniel Blake”

The social service workers in Ken Loach’s surprise Palme D’Or winner, “I, Daniel Blake” sound like insane conspiracy theorists spouting their craziest beliefs: What they’re saying is almost as unbelievable as the conviction with which it is being said. The rules Daniel Blake (Dave Johns) must adhere to are Rube Goldberg-esque contraptions, overcomplicated to the point of madness and enforced by robotic bureaucrats transplanted from a Terry Gilliam satire. Do these enforcers hear how ludicrous their demands sound? Or have they been beaten into zombie-like emotional detachment by both the sheer rote of their jobs and the unspoken fear that they could just as easily wind up on the same side of the desk as those seeking help? Whatever the case, the horrifying frustrations felt by Daniel and Katie (Hayley Squires) seep into the viewer’s skin, causing the blood to boil.

Loach masterfully constructs his film as a series of small scenes, each of which give his lead actors moments to quietly shine. Johns, who gives one of the year’s best performances, is devastating as an older man who just wants to return to work. He takes a fatherly shine to the much younger Squires, equally good as a mother whose relocation situation traps her in the same giant ball of red tape that ensnares Daniel Blake. When Katie’s story arc passes through a predictable plot point, Johns’ delivery of a single line (“You’re breaking my heart, here”) shatters the familiarity of the cliché, kicking us in the gut.

Being poor is treated as a crime in our society. “I, Daniel Blake” rails against the dirty little secret that those in power secretly hope the impoverished will simply give up and go away. Its timely anger is palpable. (Odie Henderson)

9. “Love & Friendship”

In the same year that Jane Austen devotees saw her most famous work debased on movie screens via the already-forgotten atrocity that was “Pride & Prejudice & Zombies,” they also got to experience one of the very best cinematic takes on her body of work. It came via this adaptation of an unfinished novella as brought to the screen by Whit Stillman, whose previous wry comedies of manners (including “Metropolitan,” “Barcelona” and “The Last Days of Disco”) have invoked comparisons to Austen’s work over the years. This wickedly funny comedy stars Kate Beckinsale (in the best performance of her career) as a widow with a decidedly colorful past who crashes at the estate of her former in-laws while scheming to marry off both herself and her daughter to secure their futures.

Rather than the stuffy museum piece that this might have become in other hands, Stillman made an absolutely hilarious film that feels fresher and more vitally alive than most contemporary stories of late. Additionally, his pitch-perfect screenplay manages to translate Austen’s prose in such a way that the characters actually sound as if they are talking to each other instead of merely reciting a series of familiar quotations. The result is a perfect melding of sensibilities—it has the loose and relaxed feel of Stillman’s other work while still maintaining the contours of the original narrative. Stillman comes up with an ending, the element that eluded Austen herself, that is smart, ironic and deeply satisfying. Like the film as a whole, it is pretty much perfect. (Peter Sobczynski)

8. “Cameraperson”

Veteran documentary cameraperson Kirsten Johnson’s film was billed as an autobiography of sorts, but its approach was so unusual that you might not have immediately discerned that the claim was true. The first fifteen minutes feel like a footage dump by a woman who helped shoot some of the more notable nonfiction films of recent times, including “Citizenfour,” “Darfur Now” and “Fahrenheit 9/11.” There’s a bit from a documentary about the aftermath of the Bosnian war, another bit from a visit to a Nigerian hospital where a woman tries to deliver babies without proper equipment or medicine, moments from a women’s clinic in Alabama, Michael Moore interviewing a corporal back from Iraq, and so on. And then there’s Johnson interviewing her mother, or taking care of her own kids.

But after a while we start to tune into her wavelength, and we realize that what we’re seeing is a complex essay film that conveys its ideas entirely by arranging its material in certain patterns; once you figure out what particular moments or scenes have in common with others that appear before or after them, you start to deduce why the director put them there. And as the film unfolds, transitions or segues become implied: a section about the pain of loss turns into a section about legacy, which in turn gives way to a scene about the responsibility of journalists or artists toward the individuals whose stories they tell. Your mind starts connecting the dots, and you realize this is a movie about all sorts of things: about being a parent and a child, about what it means to grow old, witness tragedy, listen to confessions, search for truth, grapple with the question of whether anything you do really makes a difference in the larger scheme, and appreciate work and friendship, family and home for their own sakes; about what it means to be alive on this planet at this particular moment. This is a movie like no other, one that seems to contain several movies, several stories, many lives. (Matt Zoller Seitz)

7. “13th”

The first documentary ever chosen to open the New York Film Festival, Ava DuVernay’s follow-up to “Selma” is a brilliantly mounted American history tour that examines the ways African-Americans have been continually subjugated from the end of the Civil War to today’s “prison industrial complex” and its mass incarceration of black men. The story begins with the 13th Amendment in 1865, which abolished slavery but left a gaping loophole in the exception it made for people who’d been convicted of crimes. This opened the door for blacks to be locked up for offenses like loitering and then used as de facto slaves in prison farms and similar institutions. The practice, as DuVernay shows, entailed not only legal chicanery but also a racist mythology that saw blacks as subhuman and dangerous, a message integral to D.W. Griffith’s 1915 blockbuster “The Birth of a Nation,” which helped re-launch the Ku Klux Klan and make it a national political force. The intertwining of legal/political oppressions and mental/mythological ones has continued ever since. Even after the civil rights battles put an end to the South’s Jim Crow laws in the ‘60s, coded appeals regarding “law and order” and “the war on drugs” provided new ways of keeping blacks subservient. Passionate yet poised, DuVernay’s masterful synthesis of historical eras and evidence is quite simply one of the most powerful and compelling films ever made about race in America. (Godfrey Cheshire)

6. “Toni Erdmann”

Apart from delivering the largest and longest sustained laugh I’ve heard in a theater since “Little Miss Sunshine,” Maren Ade’s film is extraordinary for many other reasons. Had the premise been dreamed up in Hollywood during the ’90s, it would have served as an ideal vehicle for Robin Williams, ever game for playing goofy nonconformists. As Winifred Conradi, the prankster father with the titular alter ego, Peter Simonischek has none of Williams’ manic energy, but his deadpan understatement makes each of the absurdist gags all the more uproarious. After his dog dies, Conradi leaves Germany to pay a surprise visit to his daughter, Ines (Sandra Hüller), a management consultant in Bucharest. Clad in ghoulish fake teeth and a wig that appears to have been swiped off Tommy Wiseau’s head, her father’s Mrs. Doubtfire-esque portrayal of the fictional Toni Erdmann is a source of unending embarrassment for Ines, though she has nevertheless inherited her father’s compulsion for performance.

At work, she’s required to promote the implementation of outsourcing as if it will benefit her clients, knowing fully well that it will result in massive layoffs. Ines believes this is a necessary step in modernizing the corporate world, and Hüller brings enormous conviction to the character. She’s not an independent shrew in need of being tamed, but a strong-willed go-getter with a startling boldness of her own. After her father’s incessant goading leads her to belt out a show-stopping rendition of Whitney Houston’s “Greatest Love of All,” the tables shift considerably. The 162-minute running time enables Ade to mine countless moments of all their conflicted feelings. After sitting through so many interminable mainstream blockbusters comprised of half-realized plot threads, it’s exhilarating to watch a filmmaker with the confidence to luxuriate in her narrative, savoring every poignant exchange and flight of madness. (Matt Fagerholm)

5. “Elle”

While “Elle” is technically a thriller, it’s primarily a character study about an independent woman with a death wish, serious emotional baggage, and a maniacal need for control in all aspects of her life. Michele (the incomparable Isabelle Huppert) is not, in that sense, defined as a victim, though many of her actions in “Elle” concern or are related to her being raped by a masked assailant.

You can’t neatly blame her masochistic drive to unmask and be dominated by her assailant on any one motivating factor. She has a tortured past with her incarcerated father, a devout Catholic who unexpectedly snaps one day and goes on a killing spree. And she has mounting problems at her day job, where she’s treated as a domineering outsider, and is harassed by a mysterious cyber-stalker. Michele also has problems with her son, her mother, and her ex-husband. But none of Michele’s interactions really explain what motivates her perverse fixation with her rapist.

Huppert’s galvanic performance—which was partly improvised—is a huge part of why “Elle” feels as complex and thorny as it does. But David Birke’s screenplay, adapted from Philippe Dijan’s source novel, and Paul Verhoeven’s masterful—and relatively sober—direction are both so strong here. Together, the film’s three primary authors make “Elle” feel like a rebuke to any narrative that crassly uses rape to give viewers a sense of false empowerment and catharsis. “Elle” is not a traditional feminist narrative, but it is an essential one. Birke, Huppert, and Verhoeven emphasize the often-horrifying factors that lead to Michele’s dangerous decisions, but ultimately never shame her for actions. Masterfully unnerving and defiantly assured, “Elle” is the feel-bad movie of the year. (Simon Abrams)

Grief has been a common topic in film lately, including works as different as “Arrival” and “Collateral Beauty,” but no one understands it quite like Kenneth Lonergan. His masterful drama hinges on two forms of grief—the kind that announces itself years before it actually arrives, paired with the kind that comes suddenly, tragically out of nowhere. Patrick (Lucas Hedges) has known for years that his father (Kyle Chandler) was going to die, giving his grief a different tone than that of his uncle Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck), who had sorrow rain down on him in the middle of the night. As they both manage life after the loss of their father and brother, Lonergan explores how grief is not something we get over but that we learn to live with.

Lonergan’s sense of place is essential. He subtly captures the Upper East Coast of this country, one in which sports are often on television sets and crucifixes are often on walls. And he imbues alcohol throughout the piece, from the bar fights to the drama of Patrick’s mother (Gretchen Mol). Like the water on which he opens and closes his film, grief merely becomes a part of the world of the Chandler’s. It’s like God, beer and hockey—it will always be there. And so while we’ve seen many films about people getting over loss, we’ve seen very few that deal with the more complex and truthful fact that you don’t get over it—you live with it. And you use family, and unexpected humor, to learn how to do so. It becomes a part of the background of daily existence for Lee and Patrick Chandler, two film faces of 2016 that I will never forget. I feel like I know them. And that’s because of how well Lonergan knows me. (Brian Tallerico)

3. “La La Land”

[Warning-Minor Spoilers Ahead.] A musical getting awards season applause is not that unusual. An original musical developed from scratch with all new songs and cinema-specific choreography designed to be shown in old-fashioned widescreen CinemaScope? Priceless, especially when grounded true-life dramas often overshadow such flights of fancy as a pair of lovers dreamily waltzing amid the cottony clouds and glittery constellations in the sky. Some might dismiss this story of a guy and a gal chasing their ambitious showbiz dreams and each other as lightweight nostalgic fluff, especially with its top-hat tips to Hollywood’s past including such classics as “Singin’ in the Rain,” “An American in Paris,” “West Side Story” and even Disney’s tune-driven animated fairy tales.

But writer/director Damien Chazelle also anchors his melancholy romance in the realm of today where young people must often make compromises to survive. And that, along with two completely charming-if-edgy performances by leads Emma Stone as ambitious actress Mia and Ryan Gosling as struggling songwriting pianist Seb, is what makes all the difference. If you weren’t swayed by Gosling selling out his purist soul as a backup player for a pop-oriented R&B star to raise money for a jazz club or Stone baring her soul by auditioning for a movie role of a lifetime, the ending will seal the deal. There are few movie sequences this year that will produce a catch in your throat like the one in which Mia visits Seb’s successful establishment and imagines what would have been if things had gone down an alternate route. It’s a different sort of death scene, one where hopes and wishes sadly evaporate before your eyes and it is too late to ever go back. And that is as heavy as you can get. (Susan Wloszczyna)

2. “Paterson”

In “Paterson,” the story of a week in the life of a bus driver named Paterson (Adam Driver) who lives in Paterson, New Jersey, Jim Jarmusch weaves a spell—there’s no other phrase for it—where life (its routines, dreams, overheard conversations, annoyances, quiet pleasures) is a slow river of accumulated, strange and mundane patterns that could provide clues as to What It’s All About, and Why We Are Here, if we could just look at it directly. Synchronicity is not a literary conceit. It exists in the world. It could be written off as a meaningless cluster of similarities, or it could be interpreted as one of the ways in which the chaotic and harsh universe organizes itself.

Jarmusch’s film actually manages to capture the very specific and unique experience of synchronicity without underlining. As Paterson drives his bus, recurring patterns flicker on the periphery, glimpsed briefly, ephemerally. Coincidences? Maybe. But maybe not. A tilted mailbox. Glimpses of twins. A box of matches. Poetry is everywhere. Paterson is the home of one of America’s most famous poets, William Carlos Williams, who wrote, famously, “No ideas but in things.” Williams’ poems are filled with “things”—plums, a wheelbarrow, chickens, a wild carrot leaf—which, through the poem, go through a “profound change.” Williams also wrote, “The particular thing … offers a finality that sends us spinning through space.” Jarmusch’s film is filled with “things” too, the accumulation of which sends “us spinning through space.”

An enormously tender film, “Paterson” embraces community (the local bar, the craft fair attended by Paterson’s girlfriend, the passengers on Paterson’s bus), but it also embraces the private dreamspaces of its characters, some that are shared, others left hidden. What a thing it is to watch a film where everyone does their level best to be kind to one another. That’s what living in the world is all about. It’s a small miracle that Jarmusch (and his cast and production team) pull this off, although considering his body of work it’s not a surprise. “The poet thinks with his poem,” said William Carlos Williams. And, as always, Jarmusch thinks—beautifully, personally, intuitively—with “Paterson.” (Sheila O’Malley)

1. “Moonlight”

It’s the best film of the year, but one of the most impressive aspects of “Moonlight” is the way it sneaks up on you.

Clearly, it’s a gorgeous movie from the very start—a quietly beautiful tale of loneliness and heartache. In telling the story of a young, black man struggling with his sexuality, writer/director Barry Jenkins creates moments of such tender intimacy, you don’t want to breathe for fear of disrupting them.

And yet Chiron—or “Little,” as he’s known as a child in the first of the film’s three segments—lives a life of heartbreaking abuse and abandonment in the projects of Miami. Jenkins, working from Tarell Alvin McCraney’s semiautobiographical play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue,” vividly depicts a section of this city we don’t often see on film, and he does it with bracing, tactile detail and sensuous, dreamlike imagery. (James Laxton is the gifted cinematographer.)

Subtly moving performances abound, from the three actors who play Chiron at various stages in his life (Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes) to the ever-versatile Mahershala Ali as the drug dealer who functions as the boy’s father figure to a charismatic Andre Holland as the adult version of Chiron’s only childhood friend to Naomie Harris, playing his tortured, drug-addicted mother without ever lapsing into cliché.

Jenkins layers this character’s experiences on top of one another so skillfully that by the time we see Chiron in the film’s final third—when he’s renamed himself Black and built a literal suit of muscular armor to protect himself against the outside world—we realize we’ve truly come to know this person. And so when Chiron finally does allow himself to connect with another person, in just the smallest and simplest of ways, it’s devastating.

The possibility “Moonlight” offers for human understanding and even—at long last—hope is something we desperately need right now. It’s a deeply personal story with universal resonance. (Christy Lemire)

To see what RogerEbert.com contributors have on their individual Top 10 lists, click here.