Michael Moore’s “Fahrenheit 9/11” is less an expose of George W. Bush than a dramatization of what Moore sees as a failed and dangerous presidency. The charges in the film will not come as news to those who pay attention to politics, but Moore illustrates them with dramatic images and a relentless commentary track that essentially concludes Bush is incompetent, dishonest, failing in the war on terrorism, and has bad taste in friends.

Although Moore’s narration ranges from outrage to sarcasm, the most devastating passage in the film speaks for itself. That’s when Bush, who was reading My Pet Goat to a classroom of Florida children, is notified of the second attack on the World Trade Center, and yet lingers with the kids for almost seven minutes before finally leaving the room. His inexplicable paralysis wasn’t underlined in news reports at the time, and only Moore thought to contact the teacher in that schoolroom — who, as it turned out, had made her own video of the visit. The expression on Bush’s face as he sits there is odd indeed.

Bush, here and elsewhere in the film, is characterized as a man who owes a lot to his friends, including those who helped bail him out of business ventures. Moore places particular emphasis on what he sees as a long-term friendship between the Bush family (including both presidents) and powerful Saudi Arabians. More than $1.4 billion in Saudi money has flowed into the coffers of Bush family enterprises, he says, and after 9/11 the White House helped expedite flights out of the country carrying, among others, members of the bin Laden family (which disowns its most famous member).

Moore examines the military records released by Bush to explain his disappearance from the Texas Air National Guard, and finds that the name of another pilot has been blacked out. This pilot, he learns, was Bush’s close friend James R. Bath, who became Texas money manager for the billionaire bin Ladens. Another indication of the closeness of the Bushes and the Saudis: The law firm of James Baker, the secretary of State for Bush’s father, was hired by the Saudis to defend them against a suit by a group of 9/11 victims and survivors, who charged that the Saudis had financed al-Qaida.

To Moore, this is more evidence that Bush has an unhealthy relationship with the Saudis, and that it may have influenced his decision to go to war against Iraq at least partially on their behalf. The war itself Moore considers unjustified (no WMDs, no Hussein-bin Laden link), and he talks with American soldiers, including amputees, who complain bitterly about Bush’s proposed cuts of military salaries at the same time he was sending them into a war that they (at least, the ones Moore spoke to) hated.

Moore also shows American military personnel who are apparently enjoying the war; he has footage of soldiers who use torture techniques not in a prison but in the field, where they hood an Iraqi prisoner, call him “Ali Baba” and pose for videos while touching his genitals.

Moore brings a fresh impact to familiar material by the way he marshals his images. We are all familiar with the controversy over the 2000 election, which was settled by the U.S. Supreme Court. What I hadn’t seen before was footage of the ratification of Bush’s election by the U.S. Congress. An election can be debated at the request of one senator and one representative; 10 representatives rise to challenge it, but not a single senator. As Moore shows the challengers, one after another, we cannot help noting that they are eight black women, one Asian woman and one black man. They are all gaveled into silence by the chairman of the joint congressional session — Vice President Al Gore. The urgency and futility of the scene reawakens old feelings for those who believe Bush is an illegitimate president.

“Fahrenheit 9/11” opens on a note not unlike Moore’s earlier films, such as “Roger & Me” and “Bowling For Columbine.” Moore, as narrator, brings humor and sarcasm to his comments, and occasionally appears onscreen in a gadfly role.

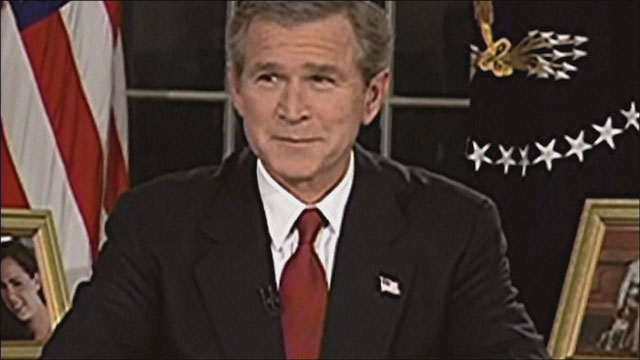

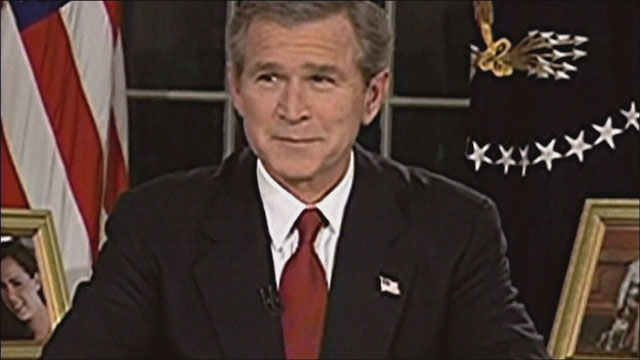

It’s vintage Moore, for example, when he brings along a Marine who refused to return to Iraq; together, they confront congressmen, urging them to have their children enlist in the service. And he makes good use of candid footage, including an eerie video showing Bush practicing facial expressions before going live with his address to the nation about 9/11.

Apparently Bush and other members of his administration don’t know what every TV reporter knows, that a satellite image can be live before they get the cue to start talking. That accounts for the quease-inducing footage of Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz wetting his pocket comb in his mouth before slicking back his hair. When that doesn’t do it, he spits in his hand and wipes it down. If his mother is alive, I hope for his sake she doesn’t see this film.

Such scenes are typical of vintage Moore, catching his subjects off guard. But his film grows steadily darker, and Moore largely disappears from it, as he focuses on people such as Lila Lipscomb, from Moore’s hometown of Flint, Mich.; she reads a letter from her son, written days before he was killed in Iraq. It urges his family to work for Bush’s defeat.

“Fahrenheit 9/11” is a compelling, persuasive film, at odds with the White House effort to present Bush as a strong leader. He comes across as a shallow, inarticulate man, simplistic in speech and inauthentic in manner. If the film is not quite as electrifying as Moore’s “Bowling for Columbine,” that may be because Moore has toned down his usual exuberance and was sobered by attacks on the factual accuracy of elements of “Columbine”; playing with larger stakes, he is more cautious here, and we get an op-ed piece, not a stand-up routine. But he remains one of the most valuable figures on the political landscape, a populist rabble-rouser, humorous and effective; the outrage and incredulity in his film are an exhilarating response to Bush’s determined repetition of the same stubborn sound bites.