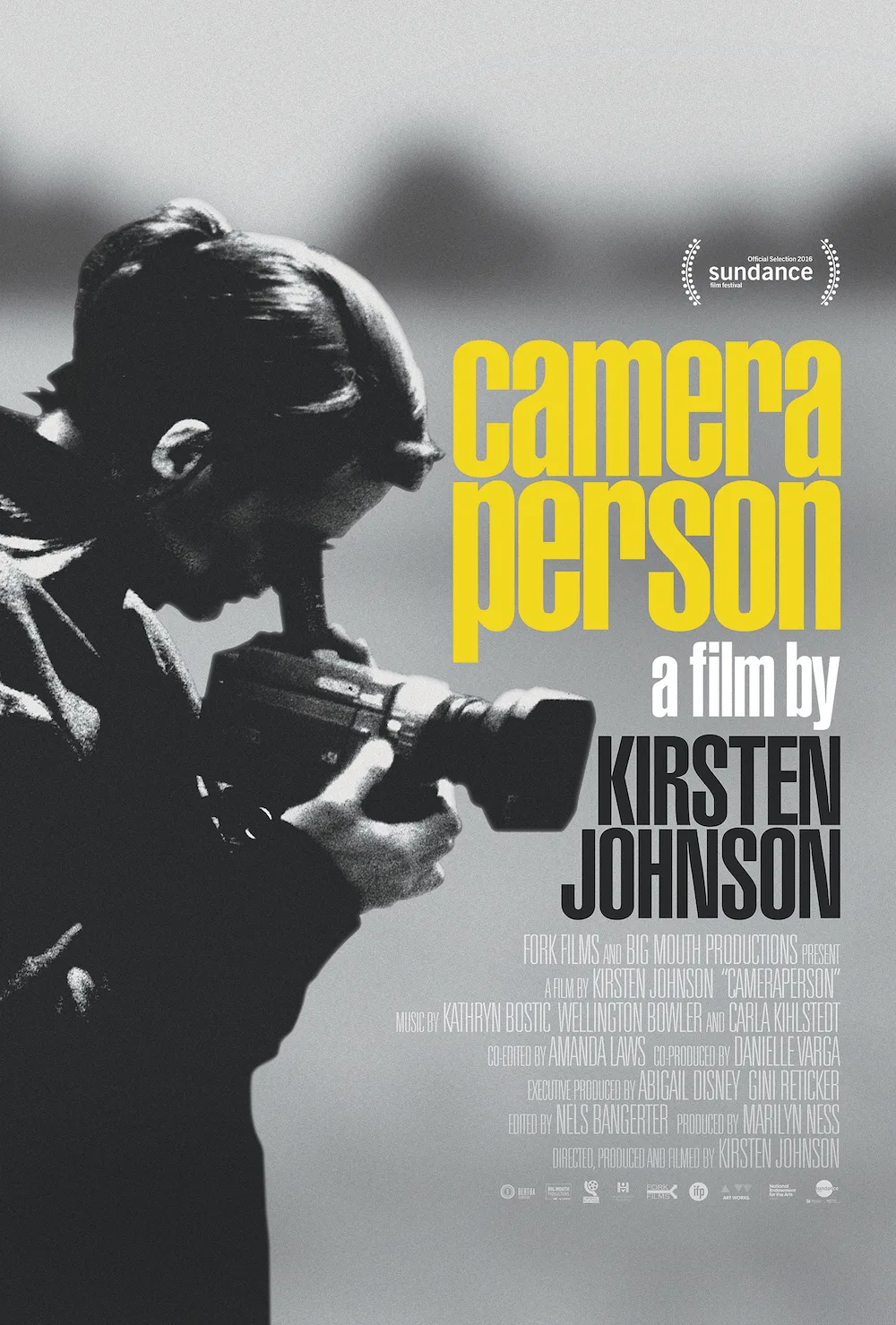

The collage film “Cameraperson” is one of the most original, challenging, sometimes infuriating documentaries of recent times. It’s well worth seeing and arguing about, but only if you can give it your full attention and glean the internal logic that went into its construction. Once you’ve done that, you will never forget what the movie showed you, or your own guesses about why it showed it to you.

It’s an extraordinary feeling, meeting a film in this way. The director of “Cameraperson,” veteran nonfiction camerawoman Kirsten Johnson, errs on the side of subtlety, which means the movie never comes to you; you always have to go to it. Compounding the difficulty is the reality of moviegoing as most viewers (critics included) often experience it. Anyone who sees “Cameraperson” is going to have to set aside a lifetime’s worth of conditioning by word-driven movies that make sure to tell you what’s happening and why it’s important every few minutes, just in case the images and sounds aren’t making things clear. Even though I tend to seek out films like “Cameraperson” and give them the benefit of the doubt early on, this film’s first twenty minutes still struck me as opaque to the point of impenetrability, perhaps even a case of the Emperor’s (Empress’s?) New Clothes. The questions that popped into my head aren’t ones that most filmmakers want to hear: What am I looking at? Why this moment, and why now? And why are we suddenly done with this moment and moving on to something completely different? Would all of these dazzlingly observed and often flat-out beautiful images have been better served by remaining in their original contexts—projects on which Johnson served as a camera operator? Is this whole thing just a glorified clip reel?

Nope. It’s going somewhere. And the destination is worth any effort the journey may require. This is the kind of film that makes you see other movies through fresh eyes and ask questions that might not normally occur to you during films that try to hide their storytelling seams.

The film begins with footage of Johnson trying to get just the right shot of a shepherd on horseback in rural Bosnia, then continues on to show us scene after scene that seems, on first glance, to be only tangentially connected to everything around it: an old Bosnian woman coyly accepting a compliment on her stylish clothes and indicating that she’s lived a very happy, mostly uneventful life; a young African-American woman in an abortion clinic talking about her decision to terminate her pregnancy; Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, crossing a New York street while telling the camera crew about “the image of the philosopher who falls in the well while looking at the stars”; a passenger jet’s shadow gliding along the tarmac, as seen through a passenger’s window; Johnson and a director trying to observe the exterior of an Al Qaeda detention facility in Yemen without arousing police suspicion. (“I’ll tell them it’s cinema, it’s a movie,” says the driver’s off-screen voice.)

But at a certain point—you’ll know it when you see it—the movie’s narrative strategy clicks into place, and you feel (perhaps before consciously realizing it) that this is not merely a collection of the director’s favorite moments from a career that took her to nations wracked by war, deprivation and oppression, and into her family’s past, and her present as a working mother employed in a field that demands a lot of travel.

This is not just one movie, it’s five, maybe six, maybe more, rolled into one.

For starters, “Cameraperson” is an autobiography of sorts—a life in filmed fragments that almost never shows the face of its main character, Kirsten Johnson, but spends a fair amount of screen time watching her mother succumb to Alzheimer’s disease. These heartbreaking moments connect with footage of Johnson’s two children. Watching them grow up, we might wonder if Johnson will one day lose her memory as well, and if these images may one day serve as a substitute for actual, physical memory—the stories that a parent is no longer able to tell a child. We may also notice that the seeming-randomness of this film’s construction is an analogy for how it feels to try to remember a life when one’s mind has been fragmented by disease, or simply by age. Maybe the movie is an analogy for how almost anyone’s mind works, even in mint condition: remembrance is not linear, it jumps around.

“Cameraperson” is also an examination of the ethics of documentary filmmaking, particularly where real-life suffering or violence are concerned: What sorts of images are permissible to show? Obviously it depends on the context, but how does one determine context? Are there rules about this kind of thing, or is editing still mainly a matter of rhythm and intuition and common sense? Is the entire process mysterious, or can parts of it be quantified and turned into rules or a code? Are certain acts, certain crimes—particularly war crimes, genocidal campaigns, mass murders and rapes and other large-scale atrocities—diminished through explicit imagery, or is it necessary to inflict distress on the viewer to make the reality feel real?

Among other real-life horror shows, Johnson covered the trial of the white supremacists who in murdered James Byrd in Jasper, Texas in 1998; after debating whether to show the filmmakers pictures of Byrd’s corpse, the prosecutors settle for hauling the chain the murderers used to drag Byrd behind a pickup truck. Later, we get a brief look at the truck. This feels like the right approach morally but also tactically (photographs of Byrd’s mangled body would have destroyed the spell that “Cameraperson” tries to weave). You might also appreciate the decision to show sites of wholesale suffering as haunted, empty spaces, without cutting to atrocity photos or horrendous news footage: Ground Zero in New York City; the site of a mass rape of Bosnia women by Serbs during the Bosnia War; Nyamata Church in Kigali, Rwanda, where 5,000 Tutsis were murdered by Hutus. But then the movie shows us a graphic scene of an infant enduring a brutally difficult birth in a Nigerian clinic, and we may have the opposite thought: that the blood and suffering helped us appreciate the story and didn’t feel exploitative at all.

On a deeper level, “Cameraperson” is an examination of storytelling choices—in particular that famous Orson Welles observation that whether a story is happy or unhappy depends on where the storyteller ends it. “Did you always dress with such style?” a filmmaker’s voice asks that elderly woman early in the movie; over an hour later, we hear that same question repeated, and because we’ve been given more information about the woman, her family, her neighbors and her country, we hear it differently, and see through it.

The various bits and pieces of “Cameraperson” collide with one another in smaller, more mysterious ways as well, creating poetic or philosophical effects. Many people, images and ideas that at first felt like mere details assume the significance of metaphor: an Afghan boy who lost an eye; an explanation of how Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder suppresses memory; the way that Johnson’s camera looks away from the faces of individuals in pain and focuses on their hands instead, while making such close-ups feel strangely more intimate than a close-up of teary eyes.

A speaker in a “Syrian Dissident Film Collective” tells an audience that when movie focuses on misery and blood, it can excite or numb viewers rather than awaken their empathy. He says filmmakers must “find a way to represent horror, to represent death, respecting the Golden Rule.” A man in the audience respectfully argues the opposite. The argument remains unresolved, just like every other idea teased out in this unusual film, which is about the things it shows and doesn’t show us, and all the good reasons for showing and not showing, remembering and forgetting.