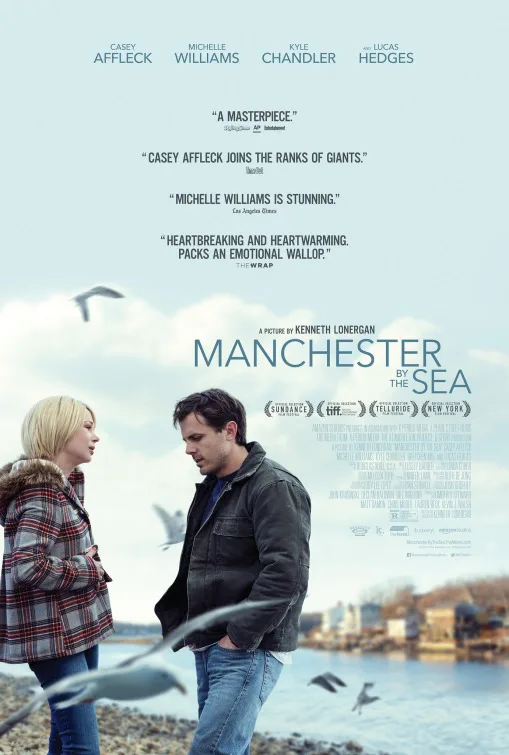

“Manchester by the Sea,” about a self-punishing, depressive loner (Casey Affleck) who slowly comes back to life after enduring a series of brutal losses, is the funniest movie about grief ever made. But that’s far from the only remarkable thing about it. This film by playwright turned filmmaker Kenneth Lonergan contains multitudes of emotions, people and ideas, in such abundance that if you ask somebody to describe it, you should probably take a seat first.

It’s a story about the complexity of forgiveness—not just forgiving other people who’ve caused you pain, but forgiving yourself for inflicting pain on others. It’s a story about parenting, of the biological, foster and improvised kind. And it’s a portrait of a tightly knit community that depends mainly on one industry, fishing, and that has evolved certain ways of speaking, thinking, and feeling. And—perhaps the biggest paradox in a movie filled with them—it’s a full-blown melodrama, packed with the sorts of events that a silent filmmaker might hesitate to jam into one film for fear of being accused of overdoing it, and yet the characters are so emotionally guarded, at times emotionally constipated, that they rein the movie in and stop it from becoming too much.

Affleck, a specialist at playing reticent, somewhat mysterious men, plays Lee Chandler, a loner who lives in a cruddy basement apartment in Boston and works as a janitor. The death of his beloved older brother Joe (Kyle Chandler, seen in many generous flashbacks) saddles him with the unexpected responsibility of raising Joe’s only son Patrick (Lucas Hedges, Redford from “Moonrise Kingdom“). Patrick’s mother Elise (Gretchen Mol, also introduced in flashbacks) is a drug addict who’s been out of the family picture for a long time. Lee despises her and is annoyed to learn that Patrick talks to her regularly and holds no grudge against her.

Although Lee’s affection for Patrick is well established, starting with the opening scene of grade school-aged Patrick clowning around with Lee on the deck of Joe’s boat, it’s a mystery to the community why Joe thought such a troubled man would be the ideal candidate to raise his only child. Lee is quiet, depressed, antisocial, a hard drinker, and inclined to fight strangers in bars. He hasn’t seen his ex-wife Randi (Michelle Williams) in years, and any time he ventures into Manchester, his old neighbors either whisper about him or glare at him.

While it’s abundantly obvious that Lee is a devastated man still picking through the wreckage of a past life, the film takes its sweet time revealing the nature of the disaster that befell him. When we finally find out what it was, we recoil at the realization that it’s even worse than we imagined, then understand why Lee not only resists the role his late brother assigned to him, but seems inclined to actively sabotage it.

On the surface this would all appear to be yet another twist on a familiar and often tedious Hollywood formula, the childish adult who’s forced to grow up by being forced to take care of a minor. But Lonergan has too much respect for his characters, his audience, and perhaps reality itself to indulge such nonsense. Lee’s backstory does confirm that he’s essentially a masochist who has spent the last several years walling himself off from any chance at happiness out of guilt. But the same flashbacks that fill in the horrendous details of his past life also show that Lee has certain tendencies that have always been a part of his character and always will be. The movie acknowledges that if, in fact, Joe made him Patrick’s guardian hoping to pull him out of his funk or somehow redeem him—and the film itself never makes this clear, preferring to let Joe’s motives stay mysterious—then it was a bad call. Everyone, Lee included, seems to realize this.

Nevertheless, he tries the best he can, despite his limitations, out of loyalty to Joe. He navigates the unfamiliar, often infuriating experience of parenting a teenage boy, serving as grumbling chauffeur for Patrick’s action-packed social calendar (he has a terrible rock band, plays on a hockey team, and bounces between two girlfriends, played by Anna Baryshnikov, daughter of Mikhail, and “Moonrise Kingdom” costar Kara Hayward) and struggling to balance his work life with the home life he never imagined he’d have. This is hard enough for biological parents and children in non-grim circumstances. These two are partners in mourning, and even though they’re too macho and sarcastic to discuss their bond openly, the wounds make themselves visible in other ways, most vividly in arguments about Patrick’s complicated love life, the fate of Joe’s beloved boat, and how best to dispose of Joe’s remains (Patrick wants him buried, but it’s a snowy winter and the ground is too hard, so they have to stash him in the freezer at the funeral parlor until spring).

Most of these details make the film sound unbearably dark, but while “Manchester by the Sea” does sometimes dive into pits of despair, most of the time it’s a dry comedy. Lonergan has a fine eye for little indignities that turn tragedy into farce, as when emergency medical technicians repeatedly fail to collapse the legs of a gurney so that they can load it into the back of an ambulance. And his playwright’s ear for deadpan exchanges is as keen as ever. Some of the most amusing bits in “Manchester by the Sea” take a moment to register because they aren’t jokes, just records of people talking. “What happened to your hand?” Patrick asks Lee at the dinner table, noting a bloody bandage that Lee applied after smashing a window with his fist. “I cut it,” Lee mutters. “Oh,” Patrick says, barely looking up from his plate, “for a minute there, I didn’t know what happened.”

Lonergan has made two other classics, “You Can Count on Me” and “Margaret”; the latter was released to theaters in a butchered though still compelling version, so if you haven’t seen it yet, watch the expanded cut, which is available on DVD and online. His first film was a compact, perfectly shaped, poignant and hilarious movie about a brother and sister (Mark Ruffalo and Laura Linney). “Margaret,” starring Anna Paquin as a young woman who accidentally causes a bus driver (Ruffalo) to kill a pedestrian, is a much grander, messier, more ambitious work, a film of statements as well as poetry, mingling gallows humor, suffering, introspection and hope. If you could somehow extract the experimental structure and darker moments of the second film and merge them with the compassion and wit of “You Can Count on Me,” you might end up with something like “Manchester by the Sea,” which carries itself like a traditional, even old fashioned drama set in the real world, but takes all sorts of liberties in arranging its characters and distributing its most crucial bits of plot information. Not every cut, transition or rhythmic gamble works, but it doesn’t matter. The movie is so filled with life in all its splendor and awfulness that you’re always more interested in finding out what’s around the next bend than judging the effectiveness of whatever just happened.

Most of the film’s scenes are short. A few clock in at less than thirty seconds. Lonergan and his editor Jennifer Lame stitch them together with an intuitive grace. But mosaic is not the film’s only mode. “Manchester” packs its first half with audaciously placed, surprisingly long flashbacks (some repeatedly interrupting a very brief physical action, such as a character exiting an office), and stocks its second half with boldly theatrical moments of confession and confrontation that are likewise allowed to play out as long as they need to. A conversation between two characters on a street corner in the story’s final stretch becomes a duet of mortification and mercy that stacks up with the best of Mike Leigh (“Secrets and Lies“). It goes on for several minutes and consists of nothing more than alternating shots of the characters, but the feelings expressed within it are ratcheted up as expertly as the sense of dread you experience when watching a great horror movie. When the scene pivots and becomes something else entirely, the effect is cathartic.

At times the snowbound or saltwater-blasted images of the town and the soundtrack of soaring classical music, old soul, American songbook standards and jukebox rock seem to be joining forces to express feelings that the characters can’t or won’t express themselves. One of the film’s most devastating moments is captured entirely from the opposite side of a hockey rink; you can’t hear anything the characters are saying to each other, but it’s fine because their body language tells the story. The contrast between the characters’ poker faces and small gestures. Cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes’ sea-etched panoramas add drama to comedy and vice-versa. It’s the kind of movie you’ll want to see a second time with someone who hasn’t seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.