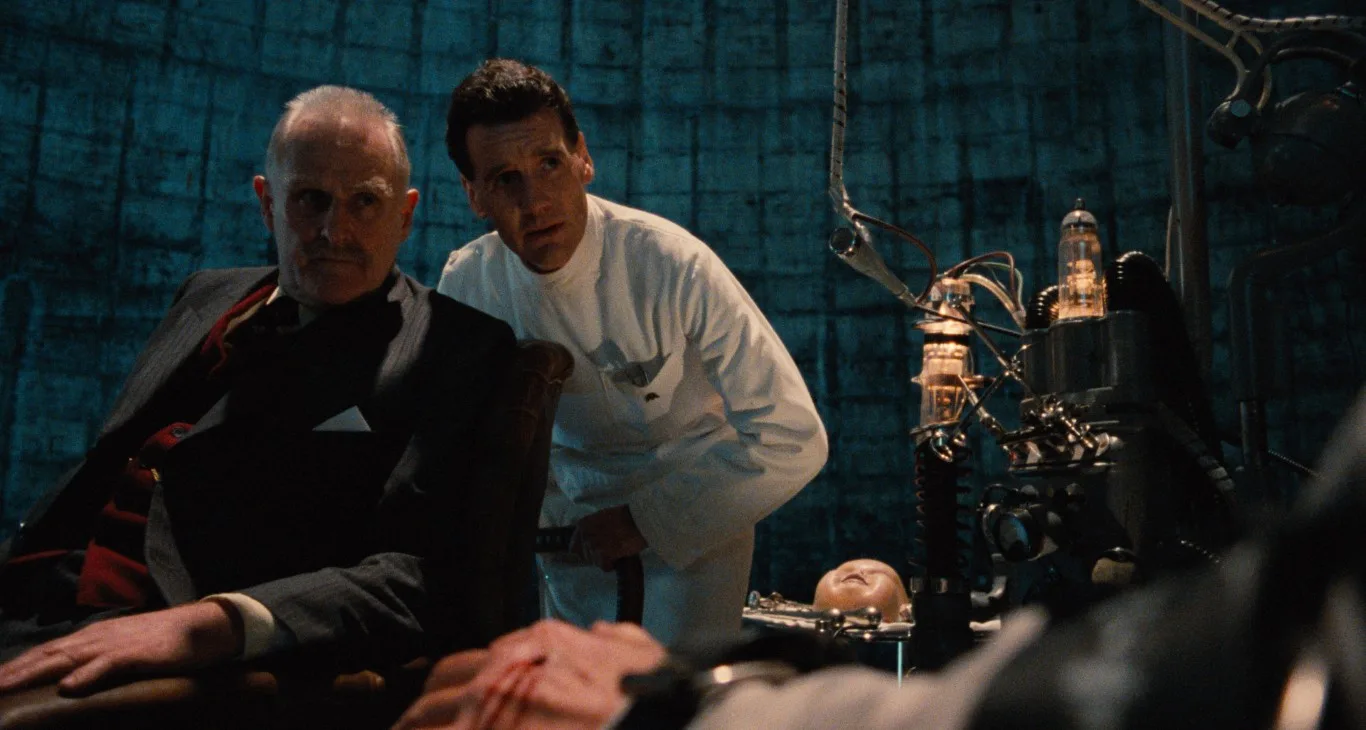

There is a moment in Terry Gilliam’s 1985 dystopian masterpiece “Brazil” where the film stops being dazzling, sets aside the Pythonesque humor, and lets humanity have a moment to itself. The lowly bureaucrat, Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), drops off a wrongful arrest refund check to the widow of Archibald Buttle, who was taken from his home by stormtroopers on a peaceful evening. It’s an unbearably awkward moment for Sam, who believes–actually believes–he’s doing the right thing by presenting the check to the widow in person. Mrs. Buttle (Sheila Reid) doesn’t let him off the hook so easily. She rips up the check, throws it at Sam, and declares, her voice rising, “He hasn’t done anything. He was good! WHAT! HAVE YOU DONE! WITH HIS BODY?!?”

It’s the film’s most devastating moment, and we watch it knowing full well that it hits close to home for many Americans today, except who knows if those living in the horrific aftermath of our current government-sponsored kidnappings will someday even get a check? Gilliam said of “Brazil” that when he wrote it, he wasn’t thinking of it as a futuristic movie. For him, it was Present Day, how he saw the world in the late ‘70s when he started putting it together with frequent collaborator Charles Alverson. Yet, we can’t help but somehow see it as “futuristic,” because how else can we describe such a complex movie so easily? That’s a different matter. But in America and the rest of the world, “Brazil” is a movie that keeps growing and changing every decade or so. It was a different movie in the years after 9/11. It’s a different movie today, perhaps more Present Day than ever.

So it’s fitting that Criterion should release a new 4K disc of the film for the film’s 40th anniversary, though one wishes they would’ve marked the occasion with something more than just the usual extras that haven’t changed since the groundbreaking laserdisc back in 1995, still one of the greatest packages of extras for a film ever assembled. “Brazil” deserves a new retrospective, though, as a means to look back on it as a piece of prescient satire, as a landmark visual stunner that has influenced many films and filmmakers, and as a film that represents why it‘s important to continue to fight for your art, no matter the cost.

I first became obsessed with it in middle school back in 1986 when the film finally came out on video. My family and I sat completely baffled at what we watched, a common experience for many first-time viewers. I simply wasn’t ready for it. At age thirteen, my tastes in movies started changing, but “Brazil” proved to be a bit of a challenge too great for me. Still, because of a paperwork oversight, my local public library forgot to put the red RATED R stamp on the VHS case and I checked it out repeatedly, just to see if I would get caught. I never did and I found myself bringing the movie home and watching it over and over again. With each viewing, the movie’s densely layered storytelling and images became clearer. By my fifth or sixth viewing, it started becoming an obsession, right alongside Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours,” also released in 1985.

For any young cinephile beginning to appreciate the language of filmmaking through editing, cinematography, score and other key elements of craft, Gilliam’s astonishing vision offers a rich tapestry of images, outlandish sets, tracking shots and wide angles to feast on that it becomes easy to forget about everything else taking place. For many, it takes a few viewings to fully appreciate the film’s aesthetic and messaging. As is typical of Gilliam’s work, he throws a lot of information at the viewer right at the start and “Brazil” rarely stops being busy. I’m not about to waste three paragraphs giving a synopsis of the film’s several story threads, since I’m guessing most readers would skip that part anyway.

One of the film’s most memorable and startling shots is a two-part fly-over of Sam’s workplace, where swarms of grey-suited men go about their day, crossing past each other in a perfectly choreographed and complex flow of movement, a self-contained ecosystem of worker bees. Files and folders get exchanged and deposited in various places while Michael Kamen’s score—one of many variations on the opening riffs of the song “Brazil”—suggests an endless loop of activity that takes place every single day in this dreary workplace. That is, until the boss (Ian Holm as Mr. Kurtzman, named after Gilliam’s editor at Help! Magazine back in the ‘60s) closes his door and everyone stops immediately and makes their way quickly to watch a classic movie on their little monitors. How fitting that one of those movies is “Casablanca,” another film in which bureaucracy plays a central role for our doomed heroes, not to mention a downbeat ending in which love does not conquer all.

Gilliam’s film is alive with visual details that become more apparent with every viewing, especially with each new video upgrade that accompanies each new format. Look closely and you can see that everything on Mr. Kurtzman’s desk is stamped with the Ministry of Information logo, including his goldfish bowl. When I revisited the film last December, I noticed for the first time in the shot where Sam is leaving the office, poor Harvey Lime (co-writer Charles McKeown) coming out of the elevator in the corner of the frame, now on crutches after Sam evidently broke his leg during one of their tug-of-wars of their shared desk. A friend of mine, also a devout “Brazil” enthusiast, remarked to me that he only just noticed the young boy in the Buttle household playing with toy stormtroopers before the real stormtroopers invaded their home. There is always something new to discover with each viewing of the film, no matter how many times you see it.

One of the key signatures of the futuristic (for lack of a better word) world Gilliam has created speaks to a kind of backwards technology. There’s an anti-logic to everything: Drilling holes into ceilings so they can do a home invasion from every angle; tiny TV screens with magnifiers; gigantic ducts protruding out of the middle of the floor of an otherwise fancy restaurant; “Thank you for calling, this has not been a recording”; having to plug the stupid cords into the phone to answer it; even Sam’s apartment is made up of removable wall panels, presumably so Central Services can get in and fix miles and miles worth of tubes, ducts and wiring that probably aren’t necessary. Finally, putting detainees into cumbersome potato sacks and fitting them with hooks so they have to be dangled on a wire during interrogation.

We can still laugh at some of this stuff, but you don’t have to look too closely to see we’re edging perilously closer and closer to this world with each headline. The only thing that dates “Brazil“ is the opening title “somewhere in the 20th century,” and certainly Gilliam had government overreach on his mind when he originally conceived of the film over forty years ago, yet for those of us who came to the film at a younger age, we looked at it simply as a Monty Pythonesque take on Orwell’s “1984” (which Gilliam claims he never read, but certainly knew about), crossed with Thurber’s “the Secret Life Of Walter Mitty.”

In the post-9/11 world, though. “Brazil”’s vision of a bent reality took on a chilling new layer of truth as Bush’s America led the un-ironically named “War On Terror,” and paranoia against anyone who might look like a terrorist entered the American consciousness. Suddenly, all those propaganda posters in the background of Gilliam’s film—”Don’t Suspect A Friend, Report Him,” “Loose Talk Is Noose Talk,” “Suspicion Breeds Confidence”—would blend in with our contemporary scenery.

Sam, like many Americans in the early 2000s, becomes convinced he is fighting the good fight against terrorism, when in reality, there are/were simply too many flaws in the systems in place to make for accurate assessments, resulting in wrongful arrests and executions. It’s even worse now, of course, as thuggish I.C.E. agents continue to dominate our headlines with their illegal invasions based on little more than someone’s skin color or place of work. It’s not even a paperwork screw-up at the root of it, but blatant racism and White nationalism. What’s more, the government sponsors it wholeheartedly, espousing their policies of fighting a war on illegal immigration while many families cry out, “What have you done with his body?” Gilliam wasn’t onto something. Variations of these policies had already been occurring in various forms around the world for decades. Even a freelance heating engineer, like Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro, unusually cast in a bit part), isn’t safe from a paranoid government’s watchful eye.

Even without these political overtones, we’ve all been living in the world of “Brazil” in our daily lives. We all have to deal with cumbersome bureaucracy and can relate to the frustration that Jill Layton (Kim Greist) feels when she tries to report the wrongful arrest of Archibald Tuttle that she witnessed. She has the arrest receipt, but it’s useless without a stamp from Information Adjustments, who were supposed to stamp it before she was sent to Information Retrieval. It’s this endless cycle of paperwork and procedure that accomplishes the opposite of efficiency. It’s not much different from going to the DMV or dealing with Veterans Affairs, health insurance, and/or Social Security. Anything that is supposed to make life easier, but ends up being a bureaucratic nightmare, is a “Brazil” moment, no matter where you live (you can throw plastic surgery malfunctions into that equation as well, which Gilliam also satirizes in the film).

There is much more to say about the long-lasting impact of “Brazil,” from the studio battle Gilliam had with Universal over its release–detailed in Jack Matthews’ invaluable book, “The Battle Of Brazil,” in which Matthews himself was a key player–to the film’s visual influences that can be seen in, among many other films, Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “The City Of Lost Children,” George Miller’s “Babe: Pig In the City” and perhaps its closest cousin, the Coen Brothers’ “The Hudsucker Proxy.” It wouldn’t have been the first, nor the last time Gilliam would have had long fights with a studio, but it remains his most notorious battle, mainly because he won, which inspired many directors to fight a little harder for their films.

The two-fold result of this battle would be lovingly preserved in Criterion’s 1995 laserdisc, which pretty much rewrote the rules on what a special edition of a film could be. It is the first instance I can think of where a laserdisc—a true cinephile’s best resource back in the day—contained not only the Director’s Cut, but the abomination that was Universal’s edit, officially known as the “Love Conquers All” version, which only saw the light of day on network television. Gilliam remains delighted that people can see what Universal was up to while he fought with them. It’s a version of the film that doesn’t make a lick of sense and Gilliam had no involvement with it, but because it is made up of nothing but alternate takes and outtakes, it remains a valuable editing tool for anyone who wants to study the craft and the choices an editor makes when putting a film together.

How does “Brazil” play today for people discovering it for the first time? I had the pleasure of hosting a screening of the Director’s Cut last December (I almost forgot to mention that it’s also a Christmas movie) in Elk Grove, Illinois, and as the movie unfolded, I could tell the uninitiated were not easily adjusting to the film’s brand of world-building. Starting with a random terrorist bombing, the Buttle/Tuttle screw-up, the Buttle arrest, the ministry discovering a mistake, and then, finally, introducing the main character of the film through a dream sequence… that’s a lot. Not surprisingly, when I asked the first-timers how they liked it, many had answers like “I was overwhelmed,” “I need to see it again,” “I’m not sure what I just watched, but I know it was amazing.”

That’s a start. We should all see it again. It doesn’t have to be the Director’s Cut either. The Universal theatrical cut (a mere twelve minutes shorter at 129 minutes) works just fine. “Brazil” still looks like no other movie, still has a fascinating legacy in terms of its release, and still resonates with our world in ways we dearly wish weren’t true. It has often been referred to as a black comedy, but like Mike Judge’s “Idiocracy,” it’s getting harder to laugh at its absurdities these days. Like one of the propaganda signs says, “Happiness. We’re all in it together,” only in one shot in the film—the moment before Sam meets Mrs. Buttle to give her the check—we see graffiti sprayed over it saying, “We’re all in the shit together.”