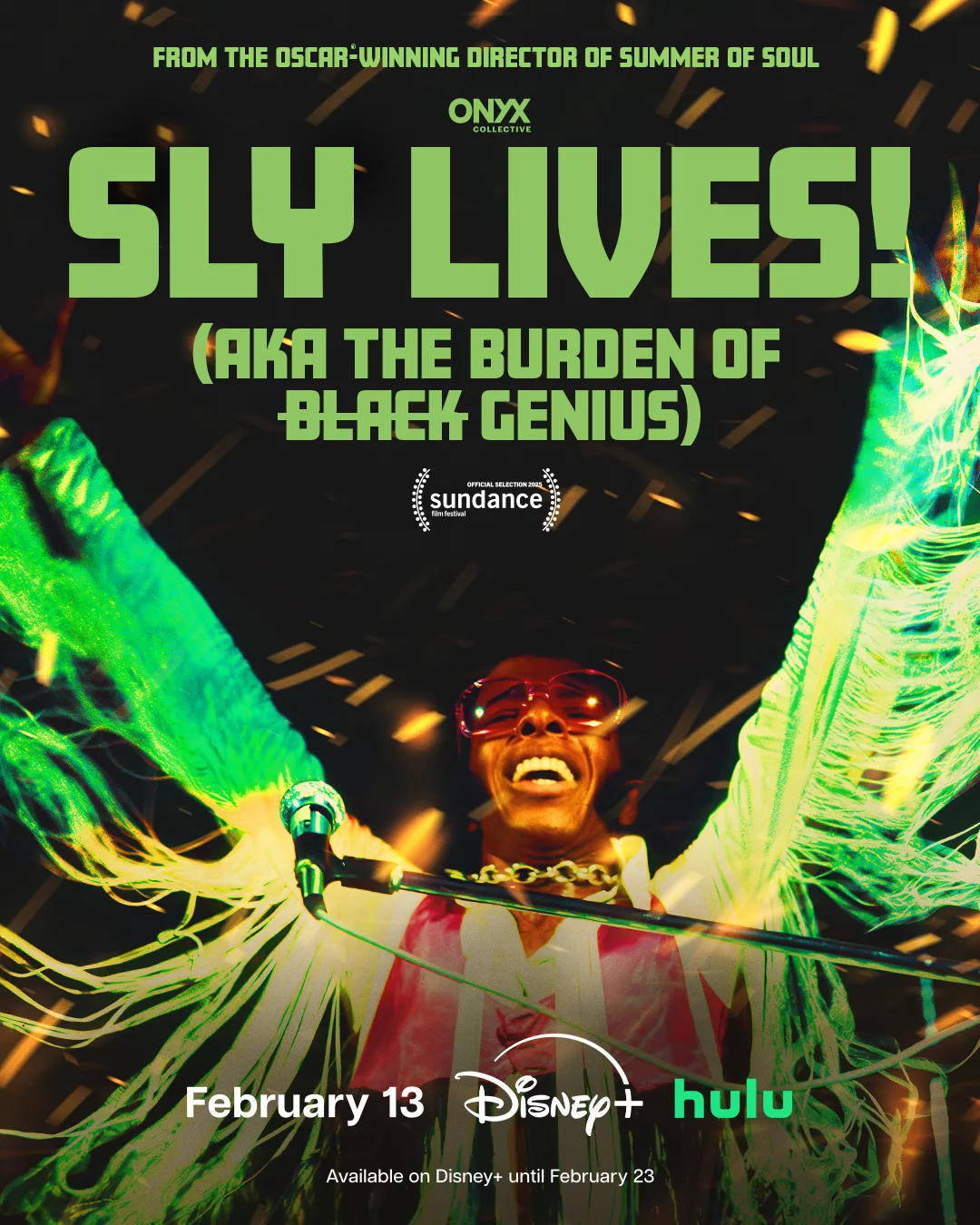

Melodically vital and bracingly frank, Questlove’s uptempo Sundance documentary “Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius)” is a sonic kick to the soul. It posits Sly Stone as a martyr to his own brilliance, a glammed-up, big afro titan from the future whose inevitable brokenness can be traced back to the weight of carrying a race and a movement.

The follow-up to Questlove’s Academy Award-winning film “Summer of Soul,” “Sly Lives!” faces obvious difficulties matching the former film’s vitality. In fact, the documentary can easily be interpreted as a companion piece to his debut by virtue of its civil rights bent, the late-1960s to early-1970s time span, and the fact that Sly and the Family Stone were the only act to play both Woodstock and the Harlem Cultural Festival (where “Summer of Soul” takes place). But “Sly Lives!” isn’t the recreation of an event. It’s the recreation of a person, Sly Stone. Powered by the hits that redefined music, this invigorating survey of the rise and fall of a boundary-pushing artist stands firmly on its own.

The structuring of “Sly Lives!” is faithfully chronological. Once a rapid-fire montage of talking heads proclaiming the innovation of Sly fades, Questlove dutifully combs through the artist’s biography: from his religious upbringing in Vallejo, California to his early forays in music in groups like The Stewart Four and The Beau Brummels, and as a disc jockey and music producer. By 1966, he formed Sly and the Family Stone, a biracial, mixed-gender band out of San Francisco that blended rock, pop, and funk to create a distinctly defiant sound that came to define the fervent desires and unavoidable turmoil of the era.

Questlove smartly parallels the arc of the band with the country. The same year the band formed, the Civil Rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. still held integrationist promise, and Sly and the Family Stone became emblematic of that hopeful future. As the non-violent movement fell apart due to the murder of MLK, Black Power took hold. Similarly, Sly and his band, composed of actual family like his sister and brother, lost their innocence. Sly turned to hard drugs and began penning introspective lyrics that spoke to his own insecurities with his place as the voice of Blackness. He also drifted away from the band, physically moving from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

In between covering these biographical facts, Questlove also breaks down the band’s earworm music. With “Dance to the Music,” for example, he deconstructs the song through multitracks, highlighting each hooky component until the totality of the melodies is apparent. He finds revealing studio outtakes of “Everyday People” that highlight how the track transformed from a soulful slow gospel ballad to an uptempo juggernaut. He also highlights Larry Graham’s instructive bass playing on “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” and the visionary use of a drum machine for “Family Affair.” I love these dissections of what makes a hit a hit. You gain a new appreciation for the inner workings of the art by seeing how it comes together.

Being a musician, Questlove has a clear advantage over other directors who take on musical subjects only to rely on a basic jukebox format. He can chart the auditory lineage of Sly and the Family Stone’s music, such as their influence on hip hop, Prince, and Janet Jackson. When music producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis discuss sampling the riff from “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again),” Questlove layers the two tracks together. It’s a sonically enthralling moment and a finely conceived highlight by editor Joshua L. Pearson.

Questlove struggles, however, as an interviewer. He didn’t necessarily need to work that muscle on “Summer of Soul,” a film that recreated a singular moment in history. In “Sly Lives!,” that skill is necessary to shape the backbone of the film’s psychological, racially defining thesis. Instead of asking these musical legends to broadly define terms like “Black genius” or “separation anxiety,” one wishes he more directly tied each component of Sly’s troubles to the specific experiences of each talking head. He does so with Chaka Khan, a singer who battled drug addiction, when he asks her what would compel someone to turn to substance abuse. But he doesn’t lean on André 3000, for example, to discuss how a band that’s considered a family breaks up. With more fine-tuning of questions, maybe the director could’ve parsed the exact difficulties of being a Black celebrity, especially in a white-dominated world that sees you purely as a commodity.

Still, Questlove manages to walk the fine line of critiquing his subjects while adding context to their fallibility. For every moment film producer Dream Hampton empathizes with Sly (specifically the loneliness he must have felt), others are frank about Sly’s self-inflicted wounds. George Clinton provides insight into his and Sly’s shared drug habit, particularly crack cocaine. Sly’s children offer their thoughts on his absence, while former band members like Cynthia Stone (through archival footage), Greg Errico, and Jerry Martini give a behind-the-scenes recounting of Sly’s increasingly erratic behavior. Through their memories and archival interviews with Sly (he didn’t provide any new soundbites to Questlove), the film paints him as a victim of the success that often overwhelms Black creatives without handwaving his troubles away.

“Sly Lives!” isn’t as eye-opening as “Summer of Soul” (a difficult hill to climb). But it’s still a clear cut above your standard hagiographic music documentary. This film sees Sly as a three-dimensional person whose brilliance should neither absolve nor condemn him. It marvels at his genius and mourns the evaporation of his hitmaking talent. It is as vibrant, colorful, and catchy as any Sly and the Family Stone chart-topper. You don’t just want to pull out their records to hear the real thing, but use this film’s knowledge as a companion to those indelible classics.

This review was filed from the world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. It premieres on Hulu on February 13.