“If the career of Christopher Nolan is any indication, we’ve entered an era in which movies can no longer be great. They can only be awesome, which isn’t nearly the same thing.”

— Stephanie Zacharek on “Inception“

Well, people certainly want to talk about “Inception” on the Internet. The opening lines to Stephanie Zacharek’s review above may sound flip, but she’s zeroing in on something crucial about the kinds of spectacle movies to which we have, perhaps, become accustomed. I remember having an argument with some younger friends back in 1994 over Roland Emmerich’s “Stargate,” which I found inert and lugubrious, but my friends enjoyed for what they called “visual splendor.” (I don’t remember how baked we were at the time.) As I believe I said back then, I’m all for visual splendor, but I don’t go to narrative movies for (just) a light show, no matter how splendiferous. (I’d rather watch Stan Brakhage for that kind of thing.)

In my hastily keyboarded notes after seeing “Inception” last weekend, I began by saying the biggest disappointment for me was that it was so contrived and remote — like a clever mechanical puzzle, but not at all dreamlike. Even more disappointing for me, I didn’t feel I had much of interest to say about it. Now, more than 200 reader comments later, I find it more fun to theorize about than it was to watch. (Seems awfully anal and pedantic for a “summer movie.”) In that post and the previous one about “Signs” and “The Prestige,” I wound up writing more in response to comments than I did in the original post, and I really enjoyed the back-and-forth. (But if you want to spare yourself my expanded thoughts — and others’ — here about what doesn’t work in the movie and read more about the implications of two of the most important shots, spoilers and all, feel free to skip to the numbered boldfaced headings below…)

“Inception” doesn’t go very deep. Consequently, most of the discussion has been about the superficial levels of plot and the much-explained but not necessarily understood rules governing the movie’s dreams. (And, of course, given the last shot, about whether it was all supposed to have been Leonardo DiCaprio’s dream — see below…) Some have noted that the movie uses dreaming (or its conception of guided, architecturally designed dreaming) as a metaphor for cinema, which I certainly accept. Glenn Kenny described it as “multi-dimensional narrative chess,” which I think is an even better analogy (though, for me, 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe might be closer to the mark). But, as Zacharek writes, it might have been easier (and more effective) “just to make a movie”:

He stretches the boundaries of filmmaking so that it’s, like, not even filmmaking anymore, it’s just pure “OMG I gotta text my BFF right now” sensation. […]

… Everything he does is forced and overthought, and “Inception,” far from being his ticket into hall-of-fame greatness, is a very expensive-looking, elephantine film whose myriad so-called complexities — of both the emotional and intellectual sort — add up to a kind of ADD tedium. This may be a movie about dreams, but there’s nothing dreamlike or evocative about it: Nolan doesn’t build or sustain a mood; all he does is twist the plot, under, over, and back upon itself, relying on Hans Zimmer’s sonic boom of a score to remind us when we should be excited or anxious or moved. It’s less directing than directing traffic.

Again, perhaps that’s a tad snarky sarcastic (I’m so over the word “snarky”!) — and I can’t concur with everything she says because I think almost anybody could out-dream this movie. One of my problems with it is how pedestrian its dreamscapes are — no matter what their functionality or how “dreaming” is meant to be re-defined for the sake of this film. All I saw were clichés recycled from other movies. (At least “The Matrix” had the then-novel 3-D multi-camera effect — and look how that’s aged.)

You might say the trouble is that the trailer is more exciting than the feature — and that’s because Nolan hasn’t been able to connect the dots, to tie his images and his themes and his stories together so that they take on resonance. They just mean what somebody says they’re supposed to mean. Owen Gleiberman summarized it this way on his Entertainment Weekly blog:

There were moments, of course, when I was dazzled. How could you not be? Yet even then, I had the feeling that those moments would have provoked virtually the same reaction of “Oh, wow!” awe if I had seen them completely out of context. Take the scene in which the streets of downtown Paris literally fold, making the movie look like “Godzilla” recast as a physics experiment. Sure, my eyeballs just about popped out in delight. But what did the spatial-bending quality of this sequence have to do with the rest of the movie? Did its relevance, in terms of explaining the universe of dreams, ever truly pay off?

That’s the kind of question that nagged at me throughout “Inception.” Too often, I couldn’t connect the movie to itself; for most of the running time, the act of trying to put together what was happening made my head hurt. I’ve discovered that going back to read reviews of it, in the hopes that my fellow critics could shed light on what I missed, has only made my head hurt more. It’s not that they haven’t done a good job. It’s that simply hearing that damned plot described, over and over again, produces the same “What the f–?” I-get-it-but-I-don’t-really-get-it sensation that the movie did.

For let’s be clear: “Inception” is a reasonably easy movie to understand… in the abstract….

And the abstract is the limbo in which the movie gets stuck. When you get right down to it, when you take the elevator all the way down to the foundation level in the basement, “Inception” is ostensibly a film about tinkering with the deepest depths of the human psyche — a man’s feelings about his recently deceased estranged father; another man’s feelings (of love and guilt) about his dead wife, of whom he can’t let go. And yet, as Zacharek observes, it’s so busy that it’s emotionally insensate. We know nothing about the characters except what’s necessary for the plot, and we care I cared even less. The father is played by the great actor Pete Postlethwaite, and he doesn’t get to do anything but appear.

OK, these are architecturally designed dreams that are structured like the levels of a 1990s video-game, so this world is intentionally constructed from obvious metaphors (secrets are kept in vaults!) and populated with characters who are cyphers. But how interesting is that to watch? For me, not very. (It’s the same problem David Cronenberg ran up against in his 1999 video-game/virtual-reality movie, “eXistenZ”: How do you make a compelling movie within the limited narrative possibilities of an immersive game?)

As Steven Boone wrote of Leonardo DiCaprio’s character’s trauma: “Cobb’s memories of his lost love and shattered family are the kind of stock images you find in a brand new wallet: pretty wife strolling a sunny beach; adorable kids frolicking in a backyard, hair backlit with a Miller Time glow.” It’s true: Nolan has not developed the shorthand necessary to create characters who register as individuals within the context of his movie-puzzles.

The truth is, some of these same criticisms have been leveled at the action/science-fiction films of Steven Spielberg (“Jaws,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” “E.T.,” “Minority Report,” “A.I.: Artificial Intelligence”), James Cameron (“Terminator,” “Aliens,” “The Abyss”) and others — and yet, I found all of those titles not only thrilling, but emotionally engaging. Think of the USS Indianapolis story in “Jaws,” the mashed potatoes scene at the dinner table in “CE3K,” the battle of the Big Bad Mamas over the little girl in “Aliens,” the desperate attempts to resuscitate Ed Harris’s estranged ex (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) in “The Abyss”… These movies, and many more, provide ample evidence that spectacle-movies can also provide thrills, suspense and emotional involvement.

Getting back to the discussions of the film’s mechanics, a couple related notes (with spoilers) about two key images in the film:

1) The last will and testament that turns into a child’s pinwheel. The ostensible “inception” of the film’s title, this image stands out as a dreamlike, transformative moment. What’s remarkable about it, as Boone points out, is this: “you’ll be astonished, not at the plot twist, but at the fact that it emerges, my God, VISUALLY, through a simple insert shot and a beautiful closeup of [Cillian] Murphy’s humbled, haunted face streaming real tears.” Until this moment, Nolan spends so much time explaining and repeating things in dialog that he seems to forget the most powerful and effective way to convey information in a movie is to simply show it. Even this moment is nearly ruined because it’s set up too strenuously, by showing us the childhood photo with the pinwheel (lifted/adapted from Dorothy Valens’ photo of her missing son and his father in “Blue Velvet“) so many times that we know it has to pay off. Still, in a limited way, it’s the most moving thing in the picture.

I’m wondering how much expositional dialog could be removed from the film to make it work on a less literal, more visceral (yes, dreamlike) level — where most good movies grab hold of us. In response to an earlier comment I wondered if we really needed all that set-up for the three-level jolt (the van falling off the bridge and hitting the water; the timed explosives in the elevator shaft; Murphy’s defibrillation in the mountain fortress). Might it have been more intriguing if we had to do a little work — if were allowed to notice for ourselves (through the way the film was intercutting them) that these three events were being synched up and had to wonder what happened next? (I cited the example of E.T. watching John Ford’s “The Quiet Man” on TV, while Elliott acts out a scene between John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara in science class. That’s not explained — it just happens before our eyes and is presented in such a way that we understand it without a word of explanation.)

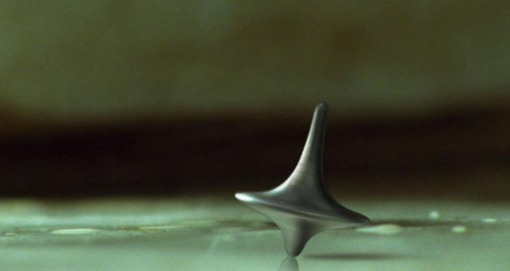

2) The spinning top in the last shot. Again, the significance of this talisman (I don’t remember the movie’s term for it at the moment, but it’s supposed to be a solid object that lets you know if you’re still dreaming) is reinforced so many times that you can’t avoid it, and the movie gets a little last-minute suspense out of holding on it in the final shot. If it keeps spinning, what we’re seeing is still a dream; if not, it’s real. But does it matter? Once more, I apply the Barton Fink Box Test. As Joel Coen phrased it: “The question is: Where would it get you if something that’s a little bit ambiguous in the movie is made clear? It doesn’t get you anywhere.”

It is clear from the first scenes of “Inception” that our main character, Dom Cobb, has a dream-memory problem with his dead wife, Mal (Marion Cotillard). We learn through Ariadne (Ellen Page), whose purpose is to guide Cobb out of his own labyrinth (or, at least, elevator) of guilt and grief, that until he deals with his own problems, he cannot be reunited with his children and Mal is going to keep interfering with his dream-extraction missions.

The process of “inception” has been done only twice — first , and disastrously, with Mal, and now in the mission that takes up most of the movie. The two inceptions are intertwined and we know from early in the film that one cannot be accomplished without resolving the other. That concept is front and center for the whole movie. So, does it matter if the top is still spinning at the end — if it’s “all a dream”? I think not. Cobb either worked out his issues with his dead wife in one dream or another. That’s the premise of the movie either way. (Cronenberg built the question into “eXistenZ,” too: “Tell me the truth, are we still in the game?”)

Dileep Rao, who plays Yusuf the chemist, said in an interview with Nick Confalone, that he finds the idea reductive and a bit of a cheat:

[Cobb] doesn’t have to be dreaming for that growth. If, by way of example, in the last scene where Cobb ran off to hug his kids, there were a reflection of Mal in the window? That would make it far more vague and I’d say, sure. But that’s not there.

Close your eyes and listen to the sound at the end. I really do think the top wobbles and that it’s real. Cobb does go on a journey, because that’s what movies are, and I think that’s what leads audiences to this kind of speculation. Because of the story he chose to tell, Nolan is also commenting on the nature of stories themselves, all stories, which is why Leo’s change can’t be evidence that it’s all a dream.

Roger Ebert notes in a blog post about the reactions to “Inception” (“Whole lotta cantin’ going on“) that “Nolan successfully made the film he had in mind, and shouldn’t be faulted for failing to make someone else’s film.” I don’t know what film Nolan had in mind, or how successfully he realized it (David Cronenberg once told me if the finished film is 70 percent of what he envisioned he considers it an extraordinary achievement). All I know for sure is what is on the screen.

But, of course, any film can be faulted for grandiosity,* or for lack of ambition. As Nikola Tesla (David Bowie) said in Nolan’s “The Prestige,” “You’re familiar with a phrase ‘Man’s reach exceeds his grasp’? It’s a lie. Man’s grasp exceeds his nerve.” We know what’s within Christopher Nolan’s grasp. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say that I would like to see him make a film that took risks beyond those of plotting and structure, that showed real nerve. Maybe he’s not the kind of filmmaker who can work without a net. But so far his dialog has hinted at ambitions beyond the grasp of his filmmaking.

– – – –

I think Henry Sheehan’s review summed it up perfectly for me and my indifferent reaction to this movie (this is somewhat paraphrased): “Christopher Nolan’s persistent thematic idea, which is: ‘What we see is not true, it’s just a facade’. You see this in all his movies. But he never says ‘Why is it a facade, or what’s behind the facade?’ And because he never really does that in any depth, it weakens the film and it just seems like a gimmick.” Basically, there’s nothing to ‘get’ in the first place.

– – – –

* Some among Nolan’s considerable fan base are known for making extravagant claims that the films themselves do not support. That’s not Nolan’s — or the films’ — fault, of course. But you can’t blame critics for citing specific evidence in the films themselves to counter some of the unteathered hyperbole.