Knowing that the summer would bring new releases by two of today’s most “controversial” (as Entertainment Weekly might put it) auteurs — M. Night Shyamalan and Christopher Nolan (one with a critical reputation on a downward slide, the other on the upswing) — it seemed like a good time to plug some notable gaps in my experience of their filmographies. I still haven’t seen Shyamalan’s pre-“Sixth Sense” features, “Praying with Anger” (1992) or “Wide Awake” (1998), or Nolan’s pre-“Memento” chronology-shifter, “Following” (1998) — which, the credits reveal, features a thief named Cobb, like “Inception.” More significantly, I suppose, I hadn’t seen (all of) Shyamalan’s hit “Signs” (2002), or any of Nolan’s “The Prestige” (2006) — the former because it just hadn’t held my interest the first time I tried to watch it and the latter because my critic-friends who’d seen it were unanimous in finding it dull and uninspired.

Well, eventually, I had to see for myself. As is often the case when two movies are seen back-to-back, they seem to illuminate aspects of each other. (This is why the double-feature is an invaluable art, though nearly a lost one.) The two filmmakers are actually quite similar, both literalists who seem more interested in illustrating or explaining what we see rather than showing us how to see for ourselves.

What do I mean by that? Well, both movies are flat-out cheats. Shyamalan is determined to illustrate that Everything Happens For A Reason, so everything does — at least for Graham Hess (Mel Gibson) and his family. Every piece drops into place with a self-satisfied tidiness that reduces life to Life Lessons. Nolan (working from a novel by Christopher Priest) undercuts his own prestige (the final act of a magic trick) by deliberately muddling magic, science and the supernatural — giving you no reason to believe anything you see. When it comes to the final reveal (spoiler ahead!), it’s not about magic after all. It’s fantasy — more Jules Verne than Harry Houdini.

The signature shot of “Signs” is a very strange kind of reveal: a character is placed in the foreground and the camera reveals someone in front of him by dollying around his head. So, the character sees something but obstructs the camera’s view until it maneuvers around him. OK, in some respects that’s a single-shot version of the typical shot/reverse shot reveal, where we see somebody’s face looking at something then cut to what they see. But here the characters’ bodies (or heads) are used as visual obstacles — sometimes for no good reason, as when Merrill (Joaquin Phoenix) visits an Army recruiting office and is greeted by a cartoonish officer. If Everything Happens For A Reason, then what is the strategy behind this mannerism? All I can think of is what my dad used to say when I’d stand in front of the TV: “You’d make a better door than a window!”

The aforementioned recruiting office scene offers signs of another Shyamalan problem: tone. He can’t quite manage it. He likes to undercut his Serious Themes with bizarre jolts of humor and sometimes it works (though he milks the tinfoil hat joke — a good one — too many times) and sometimes it doesn’t (as in the recruiting officer’s monologue). Later in the scene there’s a totally random reveal that someone else has been sitting in the office the whole time (though nobody else in the room has noticed him, for the simple reason that he has been off-camera). I’ll say this, though: Watching a Shyamalan movie makes me marvel all the more at the quicksilver tonal shifts the Coen brothers or Bong Joon-Ho carry off with such aplomb.*

The title of “Signs” is kind of like a play on words (though not quite the Five Man Electrical Band reference you might naturally expect). It’s not just a reference to the cryptic crop circles featured in the movie’s memorable ad campaign, but to those things people look for when they’re trying to assign meanings to events in their lives — as in, “Please, God, give me a sign!” Father Graham Hess isn’t just a dad (his kids are Rory Culkin and Anna Paquin Abigail Breslin), he’s a former Reverend who lost his faith when his wife was killed (horribly, and not quickly) in a freak accident caused by a character played in the movie by M. Night Shyamalan. (He is the Agent of Destiny, you see.)

Only was it a freak accident? Not if you read the signs. If you read the signs you know that Everything Happens For A Reason. There are no accidents in such a world. All Graham has to do is put all the pieces together, believe his is Not Alone and that Someone Is Looking Out For Him, and he can turn back into Father Graham again. Fortunately for him, each of his family members has a notably peculiar character trait (suspicion of drinking water, a strike-out record, asthma) that turns out to have Meaning. In the Graham scheme of things, that is. So, when faced with another death in the family, Graham tells God he just can’t take it and (Shyamalan’s Movie God being one who never gives characters more than they can handle) the aforementioned traits prevent another Hess fatality. Voila! Father Graham is born again and resumes wearing black.

In other words: faith is simply a matter of which tragedies happen and which don’t. I’d like to think this was a commentary on the arbitrariness of belief in “answered prayers,” but Shyamalan has plotted the resolutions so tightly that there’s no room for doubt. The movie remains a storytelling-by-numbers outline, straight from a story-structure manual.

I like, too, that it takes the deaths of thousands (millions?) from an alien invasion of earth to restore Graham’s sense that life has meaning and get him to return to his old job. (Proportion, please!) The existence of accidents, coincidence, randomness, was too much for his faith to handle. But if, in retrospect, it turns out that his wife’s death was actually Part of God’s Plan — a sacrifice that helped give him the idea to tell his brother to beat on the alien with a baseball bat — then that’s enough to confirm his faith in God’s Plan. As long as he can believe that God is responsible for tragedies and miracles alike, that’s a reason to have faith! (I like to imagine what Buñuel could have done with this material.) In “Signs,” however, all you can see is the hand of Shyamalan playing God.

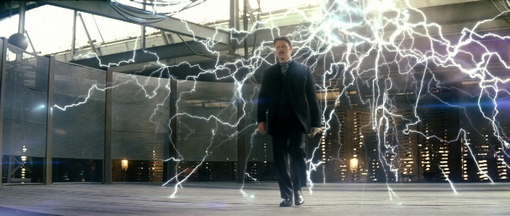

I’m trying to decide if “Signs” is one of the most immoral films I’ve ever seen (treating faith as story structure), or just one of the most puerile and schematic. “The Prestige” has a similar jigsaw-puzzle structure but lacks a point of view — not even one as tritely rigged as Shyamalan’s. The story concerns rival magicians, Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) and Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman), who employ nefarious means (aka dirty tricks) to discover each other’s secrets and undermine each other’s lives and careers.

The title, Cutter (Michael Caine) explains in the opening monologue, is the third part of a magic trick, after the Pledge (the magician presents something “ordinary”) and the Turn (the magician makes it do something extraordinary — like disappear). The Prestige is the final reveal, in which the trick is completed. It’s not enough, for example, to make something disappear; to complete the trick, the magician must make it reappear.

Nolan makes some odd directorial choices, sometimes actually cutting during an onstage magic act — which, of course, destroys the spacial integrity necessary to sustaining an illusion. (Isn’t that what CGI is for?) At the end, when he shows us how the big tricks were really done, he uses a few unbroken takes — and that’s where the cheat comes in. Just as “Signs” requires an alien invasion to restore one man’s faith in the Almighty, “The Prestige” — which is ostensibly about prestidigitation — turns out to be as much a piece of science-fiction as “Signs.” Both movies (and here come the spoilers again) are so insistently literal: Yes, the aliens are real; yes, the transported man trick is a trick — but only because both magicians use doppelgangers! As Matt Zoller Seitz said in a Facebook comment after seeing Nolan’s “Inception”: “A filmmaker as prosaic and left-brained and non-visual as Nolan should not be making a film about dreams and dreaming.” Nor about magic, either. But, looking back, Ty Burr of the Boston Globe may have had the most penetrating summary: “It’s like ‘The Illusionist’ crossed with a really hard Sudoku.” (Want to see a good, fun movie about magic that is, itself, a nifty piece of misdirection and an examination of fakery? Check out Orson Welles “F for Fake,” released in the US in 1977.)

I kept hoping against hope, as the movie came to an end, that Nolan wouldn’t insist on one unimaginative supernatural reading — but there’s no denying the final shot. It’s a deus ex machina that Explains Everything by making a sudden, desperate leap into fantasy — as if the writers had written themselves into a box and found they could not explain their way out any other way than by suspending the laws of the physical world. In retrospect, I think I now have a better understanding of the outlaw Joker’s superhuman abilities to stage seemingly impossible tricks and illusions in “The Dark Knight,” while Batman has to rely on technology and the laws of physics: Nolan doesn’t feel he has to play by the rules of the worlds he presents to us. If he needs to momentarily reach outside the movie’s reality to make something happen, he goes ahead and does it — making the impossible possible just to wrap up this particular story. I would have had more respect for a film that either respected its own internal logic (and its audience), or that left a little more room for ambiguity and mystery. Literalism in fantasy is a terrible combination.

– – – –

* I fondly recall Manohla Dargis’s Cannes report on “The Host” (2007), which she said “has been alternately described as a monster movie and a science fiction thriller, but is also a comedy, a family drama, a political critique and, at times, a seriously scary freak-out. Mr. Bong can shift moods and tones on a dime, and when the loudly appreciative audience wasn’t laughing at the witty dialogue it was shrieking at tensely wound scenes as effective as any in Steven Spielberg’s ‘War of the Worlds.’ ” That’s a pretty good description of what Shyamalan is going for in “Signs,” but wasn’t able to pull off.

WARNING: PLEASE ASSUME THERE ARE SPOILERS THROUGHOUT THE COMMENTS BELOW.