In a country where you are what you do, what happens to a worker who loses his job?

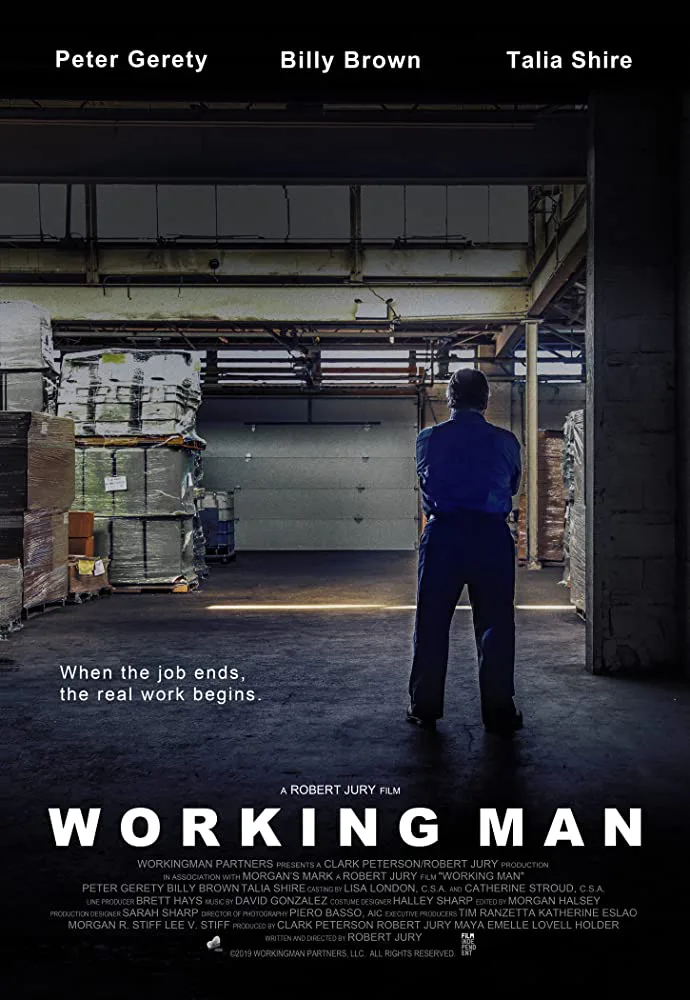

“Working Man,” the first feature from writer/director Robert Jury, spins that question into an intimate drama shot in greater Chicago, using the city’s mostly defunct manufacturing base as atmospheric backdrop for the characters’ fight for dignity. It’s a bit too gentle for its own good, and ultimately has trouble settling on what, exactly, it intends to say about its characters and their struggles. And there are one or two plot elements that muddy the film thematically even as they add surprise and complexity to the characters.

Still, this an impressive debut movie, revolving around the sorts of lower middle-class people rarely seen in American cinema anymore, told in a style that’s just as much of a throwback. It gives veteran character actors a chance to shine, not just in lead roles but supporting parts and one-scene cameos written so thoughtfully that you can picture the character starring in a movie of their own.

The film’s beleaguered hero is Allery Parks (Peter Gerety), a senior citizen who has worked for decades at New Liberty Plastics, the sole remaining factory in an area that used to be filled with manufacturing companies. We later learn that it had 500 employees when it opened but has since shrunk to 25, all of whom are laid off. In a flourish that evokes Laurent Cantet’s excellent 2001 film “Time Out,” about an office worker who gets laid off but doesn’t tell his wife and continues to leave the house and return each day as if he still has a job, Allery sneaks into the now-shuttered plant, cleaning and polishing dormant machines and taking lunches in the now-deserted break room.

Allery’s former coworkers live on the main street down which Allery trudges each day with his lunch pail. They find Allery comical at first, then irritating, then mysterious and unnerving. Allery’s wife Iola (Talia Shire) observes the strangeness without pressing her husband to explain what’s happening to him, then starts to chafe at his wordless stubbornness and worry that he’s having a breakdown—not just about his job loss, but a past trauma that they’ve both swept under the rug, and which seems to have been reactivated by the layoffs.

Things escalate when the neighbor across the street—a beefy, genial single man named Walter Brewer (Billy Brown) who used to work on the factory floor with Allery—takes an interest. It turns out that Walter has a sense of purpose as a result of observing Allery. He has a spare set of master keys that he made when the factory manager asked him to replace some windows a few years back, so he starts accompanying Allery to the factory and letting them both inside through the front door as if they still have proper jobs there. He tries to get to know Allery—no easy task, since Allery is as communicative as a statue—and enlist him in a wild scheme: he says he’s contacted the clients who had unfinished orders when the factory shut down, and they told him that if the workers finished them, they’d pay for the merchandise. If he and Allery can get the rest of the staff to come back, Walter insists, management will realize the value of the place and open it again.

This sounds like a fantasy, and it probably is. But it reawakens hope in the neighborhood, and pretty soon the factory is humming again, the neighbors and the local media are paying attention, and management is wondering what the hell is going on down there and whether they should stop it or allow to play out.

“Working Man” is the kind of movie that used to be common but that has largely vanished in the United States, along with the world it portrays. But this is less of a cry of rage or a depressed lament than a borderline fable, focusing on the spirit of people whose skills are no longer needed or appreciated in the new economy. Jury and his crew pay loving attention to the textures of small row houses, grimy machinery, and off-the-rack coats and work shirts and jeans, and the way bluish dawn light and deep orange streetlights etch city streets and tired faces. As shot by Piero Basso and the father-daughter editing team of Richard and Morgan Halsey, the film is a throwback to 1970s working-class character portraits like “Norma Rae” and “Rocky” (which Richard Halsey edited), as well as an American answer to films by UK-based directors like Mike Leigh (“High Hopes“) and Ken Loach (“Sorry We Missed You“), though softer, and without the corrosive, despairing edge those filmmakers so often bring.

Jury asks a lot of modern audiences who have become accustomed to continual, often spectacular stimuli. This is a movie that you really have to watch in order to get anything out of it. A great deal happens inside of the characters, some of whom are uncommunicative, and most of whom seem to have little access to their own emotional interiors. If you summarized the whole plot you’d have a list of people doing ordinary things, like walking and driving and shopping and chatting on porches and, most of all, eating meals. (This is a great food movie in which all of the characters are associated with foods that their character would absolutely be obsessed with, like Allery with his sad little Braunschweiger sandwiches and Iola with her homemade peach pies.)

“Working Man” is sometimes observant to a fault—it can be a bit repetitious even by the standards of a film in which repetitive rhythms are everything—and once it gets into the respective backstories of Allery, Iola and Walter, you may rightly start to wonder how any of it actually connects to the larger story of the long-gone manufacturing base in the United States and the decommissioning of its former workforce. The score, by David Gonzalez, is just right for the story—a lot of it is built around repeating three- and eight-note melodies that have a sort of “factory rhythm”—but there’s too much of it, and sometimes it intrudes in scenes where it might have been better to let us appreciate the silence in the rooms where characters are going through their struggles.

Still, there’s a lot to like here, from the overall sensibility to the little details of costuming that tell you everything (such as Allery’s lovingly weathered lunchpail and Walter’s porkpie hat, which evokes the sorts of barrel-chested sad-sack dreamers that Burt Lancaster played once he passed 50) to the meaningful but never ostentatious framing of shots (as when Iola calls a young pastor over the house to see if Allery is having a spiritual crisis; he excuses himself for a moment, and you see Allery out of focus in the background behind Iola and the pastor, putting his coat on and opening the front door).

Most of all, it’s a showcase for its actors, who seem energized by the opportunity to play characters who can’t be neatly summarized. Gerety is a specialist in laid-back East Coast gravitas whose resume includes “The Wire,” “Brotherhood,” “Sneaky Pete” and “Ray Donovan.” This might be a career-best performance, and it’s almost entirely internal, expecting you to guess what the character is thinking and feeling based on how he looks at people, or looks away from them.

Brown, a familiar face from TV’s “Sons of Anarchy” and “How to Get Away with Murder,” has a powerful physicality—he’s built like a tank—but he uses his body delicately and precisely. This is a rare performance where the actor seems to have thought up a distinctive way for his character to do everything, even actions as basic as putting on a coat, sitting up from a weight bench, or lighting a cigarette. Shire, another “Rocky” veteran, isn’t just playing an older version of Adrian Balboa. There’s a whole imagined history in the way that Iola looks at her husband as he sits sullenly across from her at the table, and she gets to play a scene with a friend late in the film about feeling lost in her own marriage that’s devastating because it rings so true. The supporting cast is perfection; standouts include Ryan Hallahan, exuding entitlement as the appallingly young executive sent to put Allery in his place, and Patrese McClain, who has one short scene in a coffee shop so packed with emotion and character detail that it feels as substantial as other people’s feature-length performances. She’s terrific.

This a good movie with a big heart.

Premieres on VOD today, 5/5.