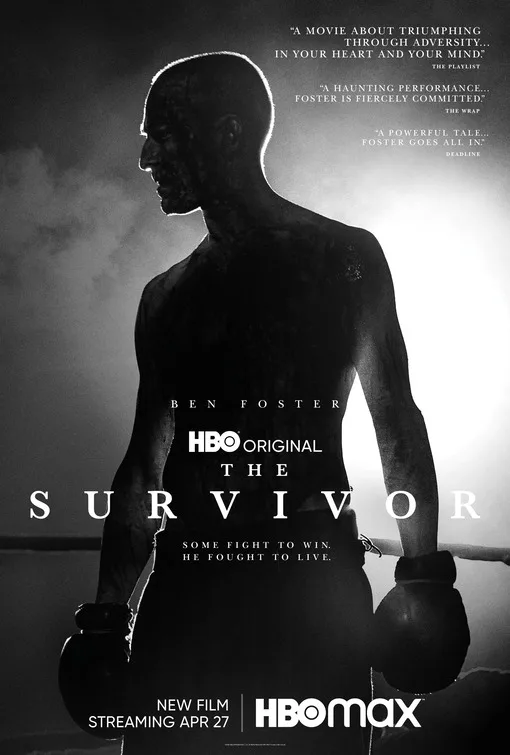

Like its lead character, and the actor who plays him, Barry Levinson’s “The Survivor” initially presents as familiar and comprehensible. The biographical drama then proceeds to surprise its audience, not with plot twists—we’re told at the outset what the character’s issues are, and have a pretty good idea of where the story is going to end up—but with how it keeps finding little ways to complicate and deepen every relationship and moment.

Ben Foster stars as Harry Haft, who made it through the Holocaust by fighting fellow inmates to the death in matches staged for the delectation of the camp’s Nazi officers, who bet on the outcome. Haft’s champion back then was a Nazi officer named Dietrich Schneider (Billy Magnussen), who got the bright idea of managing Harry after he saw him beat another officer for threatening violence against another inmate. Ordinarily the punishment for such an act would have been death, but Schnieder saw Harry as a way to make some money and stand out from the other officers; thus a parasitic relationship born. The bulk of the movie is set in the “present”—which is 1949, when Harry trained to fight heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano (Anthony Molinari), who was so fearsome that one opponent described being in the ring with him as trying to fight an airplane propeller.

But while the above makes “The Survivor” sound like a sports movie with an element of Holocaust lament (and it definitely is that), what Levinson and screenwriter Justine Juel Gillmer have concocted is a psychological drama whose first inclination is to always think about what events felt like, and what, in a larger sense, they meant, rather than concentrating exclusively on what’s next.

Levinson burst into Hollywood with the low-budget drama “Diner” and never entirely departed from the “a bunch of guys hanging out and talking” impulse, whether in the capitalism satire “Tin Men,” the family memoir “Avalon,” or the gangster picture “Bugsy,” starring Warren Beatty as a brutal Jewish gangster who founded Las Vegas. “The Survivor,” surprisingly and often with unexpected buoyancy, is another work in this vein, always choosing character and dialogue over the mandate to constantly drive the plot forward to the next big event. Gillmer’s script gives Harry lots of opportunities to interact with the supporting ensemble, which is composed exclusively of pros who are so good at what they do you’re always happy to see them. And none of their characters quite end up being the purely functional cardboard cutouts you initially assume they’ll be.

Vicky Krieps plays Miriam Wofsoniker, who works at an agency that tries to help survivors find loved ones who vanished during the war but that they believe may still be alive. When Harry shows up looking for help in finding his wife, whose disappearance obsesses him, you assume the film is positioning a love story wherein a man who is dead inside comes back to life, but that’s not how it plays out. John Leguizamo’s Pepe and Paul Bates’ Louis Barclay are introduced as two of Harry’s trainers, and Danny DeVito at first fills a similar role as one of Marciano’s trainers, Charlie Goldman, but any assumption that they’re mainly here to cheer the hero on and train him up is intriguingly subverted by how “The Survivor” treats them as a way to discuss the cold-blooded and self-serving arbitrariness of hatred.

Goldman, whose birth name is Israel, ends up offering Harry two days of training so that he won’t be completely destroyed in the ring. The upshot is a lovely film-within-a-film wherein a Black man, a Puerto Rican, and two Jews go upstate and seem to spend as much time contemplating their relative status within WASP-run America as they do working on Harry’s hooks, combinations, and footwork. The sequence is classic Levinson, filled, like the rest of the movie, with instantly quotable lines, as when Goldman exits an outhouse in the forest and grouses, “There’s stuff in there from the Revolutionary War. Aaron Burr probably dropped a load there.”

Similarly, Peter Sarsgaard’s newspaper reporter and photographer Emory Anderson at first seems like one of the most boring of all movie devices, the interviewer or witness that the main character tells their story to. And yet that relationship also moves in fascinating ways, dispatching quickly with the “as told to” device, and skipping ahead to the publication of Emory’s story and the hostile reception it sparks in the Jewish community among people who now consider Harry a traitor. When Emory shows up again in a different scene, we realize that the point of this dyad of characters is to let the film ruminate on what it means to have one’s story told, as well as the implications of serving up another person’s suffering as entertainment in a commercial enterprise (the media).

Even Dietrich turns out to have unexpected shadings. But the script takes care to present his justifications for participating in the Nazi genocide (which to his mind is comprised of much cruder people than himself) so that they give us insight into his tortured rationalizations, rather than suggesting that he’s somehow a “good” Nazi. A long, complex scene between Harry and Dietrich out in the woods beyond the camp finds Dietrich citing all of the regimes throughout history that chose an enemy within to destroy in order to build their empire. His explanation is presented in such a way that we understand he’s mainly an opportunist doing whatever he needs to do to rise up through the world, and that rather than making him less awful than the Germans who lustily participate in extermination, it’s more like the joke, “What do you call a Nazi and nine people sitting at a table having nice dinner with him? Ten Nazis.” “I don’t hate Jews,” he assures Harry. “That kind of passion is for simple minds.” That the result of his finer sensibility is still millions of deaths seems not to occur to him.

Haft’s tortured complicity in his own exploitation is also explored, both in the present and the past. The hero repeatedly tries to explain to others that he was only doing what he had to do to survive, and that it’s wrong to judge others for making such choices during a genocidal war. He then says or does things in another scene that get across the idea that he hates himself for being alive, and that he worries that all of his attempts to add context to his own story are a way of not facing himself.

Foster has been excellent for so long, in so many different roles, that it’s starting to seem as if his subtlety and respect for the viewer’s intelligence is what’s kept him from winning major awards. He gives one of his very best performances here, an incarnation of a real man that has as much imagination and commitment as Robert De Niro in “Raging Bull” and Jamie Foxx in “Ray.” The character and the performance incarnate the movie’s overall approach: you look at Harry in the first few scenes and think this is another strong-silent but suffering mid-20th century man, the kind that Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro often played. But this, too, all gets upended, as we learn that Harry is quite self-aware, and lucid in describing himself when he feels he can trust his audience. Furthermore, he’s not a standard-issue brute with poetry in his soul (he can read, just not in English) but someone who is quite sophisticated in analyzing the personalities of others. (Part of his self-loathing comes from worrying that he allowed himself to be turned into the “animal” that his captors kept screaming that he was.)

Foster appears to have lost about 40 pounds to play the nearly-emaciated Auschwitz incarnation of Harry, and bulked up to play him in the scenes set after the war. He’s clearly put a good deal of thought into choices such as the character’s walk, the way he sits at a bar or in a chair, and the way he chooses to look or not look at people he’s speaking to (or that are speaking to him). But as always the case with this performer, we never see the gears turning, and there is never a hint of ostentatious audience-pandering for appreciation or applause. We’re just watching a guy who had certain things happen to him, and did certain things, and is at a crossroads in his life.

By the end, the feeling you get from thinking about Harry is reminiscent of coming to terms with the fact that your parents and grandparents were every bit as complicated and interesting as you, and equally aware of the challenges posed by the world around them during their own time, and that the preconceptions you had about their supposed limitations were really indicators of a narcissism that one must move past in order to be an adult.

Seemingly taking a lot of its cues from the classic but now woefully unappreciated 1965 Sidney Lumet drama “The Pawnbroker,” which starred Rod Steiger as a Holocaust survivor in Poland experiencing flashbacks to his concentration camp experience while living in Harlem, “The Survivor” is a flashback-driven movie. It jumps back and forth through time, but always anchors its memory-snippets to moments in the present that trigger the hero: Barclay telling Harry (in what he thinks is an inspirational manner) that Marciano doesn’t know he’s about to fight an “animal”; a Fourth of July fireworks display that makes Harry think about a bombing raid on the camp; even the simple act of walking on a beach, which makes Harry imagine his wife’s shadow joining his, and holding his hand.

The editing, by Douglas Crise, doesn’t push this technique as far as a film like “All That Jazz” or “The Tree of Life,” tending to present the past in terms of full scenes rather than snippets. But the way the images initially invade Harry’s consciousness brings a welcome quality of graceful precision to what might otherwise have felt like a familiar storytelling approach. A case could be made that “The Survivor” would be a deeper, greater film if it had been told in either a simpler or more complex way, or entirely avoided many of the standard elements in biographical movies, sports movies, and Holocaust dramas, and that is surely true.

But a good counterargument would be that this film could never have been made at this budget level (the cars, clothes, and period street scenes evoke “Raging Bull” and Levinson’s own “Bugsy”) and with this impressive a cast if the film hadn’t at least gone through the motions of seeming safe. In the end, “The Survivor” is more eccentric and original than the viewer has any right to expect, smuggling a bit of that old “Diner” spirit into what seemed like Oscar picture template—a strategy that in boxing is called a rope-a-dope.

“The Survivor” is about as sophisticated as it is possible for a big-budget movie aimed at a wide audience to be. And what lingers is not just the story and its individual events, but how Levinson considers the array of possible strategies that marginalized people take in order to get through life in one piece, listening to their explanations without ever judging them, and injecting welcome notes of humor whenever possible. “You’re eating ham,” Goldman warns Harry, in the middle of a break for lunch during their training retreat. Harry pauses for a second, contemplating whether to take another piece, then takes it, saying, “God doesn’t pay that much attention to me anyway.”

Now playing on HBO Max.