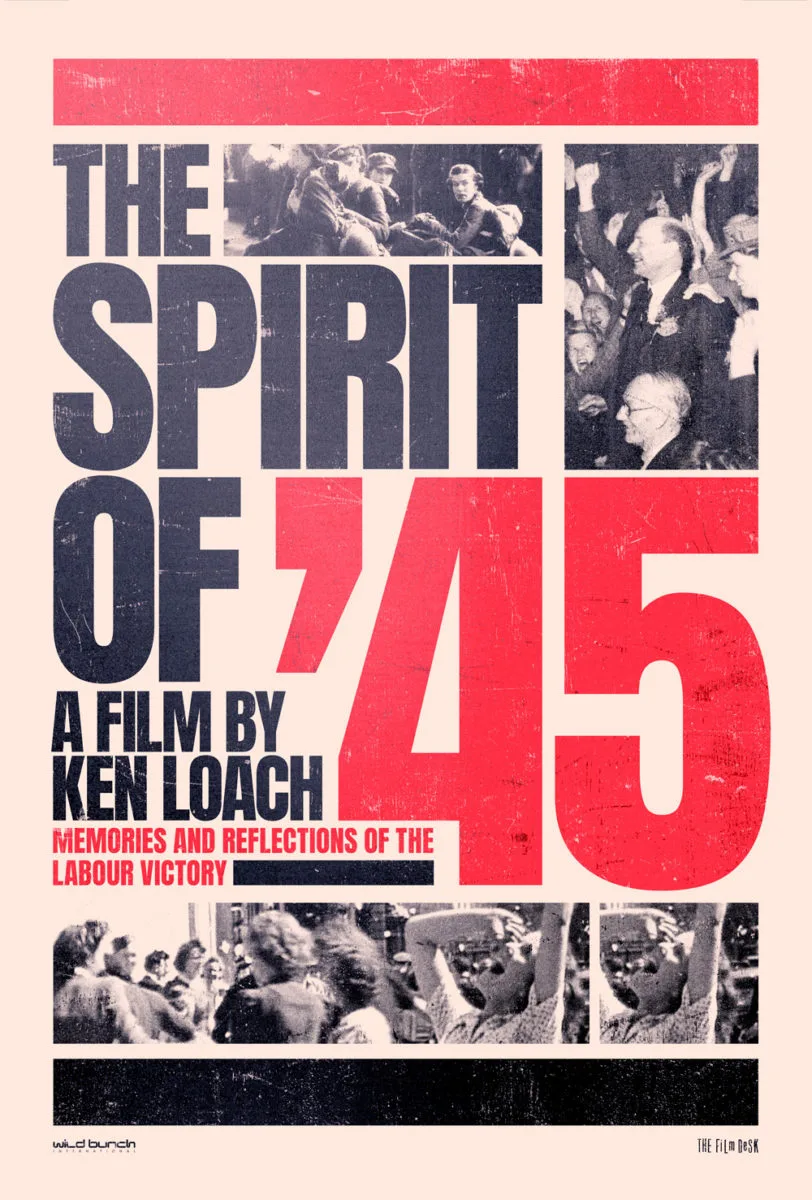

Ken Loach’s “The Spirit of ’45,” a documentary about the reinvention of British social services after World War II, explores a part of history that textbooks usually prefer to skip or distort because it contradicts messaging that government and taxes are the “real problems” in life and if people are suffering, it’s their fault.

“The Spirit of ’45” is also a testament to the power of faces speaking in closeup. Much of it is an oral history. Many of the witnesses were elderly when Loach interviewed them, and remember the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s firsthand. There are also interviews with people who weren’t alive then but heard stories from their parents or grandparents on rare occasions when the elders were able to overcome the trauma that more often made them keep those tales to themselves. They grew up poor on a level that Charles Dickens described in his fiction, barely surviving from one day to the next. In calm, even tones, they talk about agonizing deprivation that was accepted as normal by the “haves” in Great Britain.

“The slums of England were the worst in Europe,” says one witness. One elderly man talks about climbing into bed each night with his siblings and untold numbers of fleas, being bitten all over his body as he slept, then getting caned at school the next day for having “dirty knees.” There were rats and roaches, too. No rugs, because no one could afford them. Many interviewees ate potatoes and bread every night. Drippings, one witness says, were not something most poor families experienced because they couldn’t afford meat. Dot Gibson, the General Secretary of the Pensioner’s Convention, talks about how her grandfather used to take his only suit to the pawn shop on a Monday, use the money he received for it to buy food for the family and pay to treat one of his son’s kidney ailments, then get the suit back after he got paid on Friday so he could wear it to the pub.

The Labour Party won a surprise landslide victory in 1945, following the end of Britain’s involvement in World War II, routing the coalition led by Prime Minister Winston Churchill. As Loach explains, part of the rejection was due to Churchill being perceived as a wartime leader who wouldn’t know how to handle peacetime challenges, as well as the lingering stink of appeasement of Hitler that clung to Churchill’s party (although Churchill personally was against appeasement).

But another, possibly bigger factor was people wondering why the United Kingdom could afford to spend billions to fight a World war at a time of deprivation (things were economically bad before, too) yet supposedly lacked the funds to improve the lives of non-wealthy citizens afterward. When Labour won, a raft of social programs was passed to ease the suffering of the poor and working class. The jewel was the creation of a national healthcare service, something that the United States of America has barely begun to try to equal and that many decades of conservative agitprop in the United Kingdom have failed to eradicate.

One of the chords that Loach repeatedly strikes here is that in democracies, and perhaps every other sort of government, money spent on war is somehow never counted as spending, and certainly never as irresponsible spending, except perhaps by a handful of legislators who identify as socialist and therefore have no power. There’s always some reason concocted to explain why defense spending is urgently necessary and to question it is unpatriotic and perhaps treasonous. This is the case in the United States as well. It’s the same all over the world and always has been.

But Great Britain briefly and anomalously refused to accept it in 1945, and as Loach tells the story, it took another 34 years for the election of Margaret Thatcher (a year before Ronald Reagan in the USA) to start dismantling the social architecture that had been created and begin returning the lion’s share of the nation’s wealth to the rich.

The 1942 Beveridge Report—officially titled “Social Insurance and Allied Services”— was a factor in the socialist victory three years later. The impetus was its author William Beveridge’s realization while working in the private sector that philanthropy was useless as a means of truly improving the lives of the poor; its main purpose was to make rich people feel better about hoarding money and resources and let them put their names on things, and the only way to effect widespread, deep, positive change was to seriously tax them and fund social programs. Beveridge said the 1940s were “a time for revolutions, not for patching.” (You can read about the report here.)

This is a terrific movie all on its own, giving us details about a specific period of history in a specific country that commercial films and TV platforms for obvious reasons won’t touch. It’s so compelling in its account of the immediate pre- and postwar eras that when it jumps ahead and feels like it’s rushing to get its points in, the film is diminished just a bit, but that’s a small complaint. “The Spirit of ’45” will be particularly fascinating to anyone who’s followed Loach’s career as a dramatic filmmaker with a socialist vision. In films as diverse as “Kes,” “Riff-Raff,” “Raining Stones,” “Land and Freedom” and the recent “Sorry We Missed You,” he chronicles the lives of the poor and working-class, past and present, often in areas of the United Kingdom that are rarely shown onscreen, and always makes sure to provide social and political context for why they have to work themselves practically to death to afford the basics. This documentary could be screened as a prelude or postscript to anything and everything he’s done.