Strange that the British “Riff-Raff” and the American “Mac” should come out so closely together, both dealing with the everyday lives of working men in the construction trades. The differences between the two films are revealing about the differences between the two cultures. John Turturro’s “Mac” shows a young carpenter determined to work hard, get ahead, start his own construction company, and buy a piece of the American dream. Ken Loach‘s “Riff-Raff” shows laborers who are alienated from the very idea of management and see themselves as proletarian outsiders.

Partly that’s a function of the more rigid class system in Britain and the relative freedom of social movement in this country.

It also reflects the different places that the two screenplays come from. “Riff-Raff” was written by Bill Jesse, a construction worker, who died as the film was being completed. It reflects his unromantic, irreverent view of the world. “Mac” was written by Turturro, who based it on his own father’s life. The title character, the son of Italian-American immigrants, is able to move up in the world, just as Turturro has.

“Riff-Raff” centers on a construction job in London, where 19th century housing, recently renting for very little, is being renovated into town homes for the rich. The workers on the job are nomadic and homeless; many come from outside London and live in “squats,” or empty flats, that they open with a crowbar. Their boss is a loud, aggressive site manager whose threats mostly involve his cheerful willingness to fire them.

We meet several of the workers and get to know them. One is a young Scotsman, who in the course of the film moves in with a woman who claims to be a poet and folk singer but whose most sincere interest is in drugs. Another is a lifelong leftist who analyzes the situation in terms of the class struggle.

Three are blacks – one of Caribbean descent, who wants to visit Africa, and two from Africa, who laugh at his desire.

The men form a rough camaraderie on the job, held together by a certain pride in their labor and a mutual hatred of the contractors and developers – who are cutting corners in every way they can, including safety. We also see them off the job, in pubs and in their squats, and eventually it sinks in that they don’t see much future in their work or their lives, and view Britain as a society that excludes them.

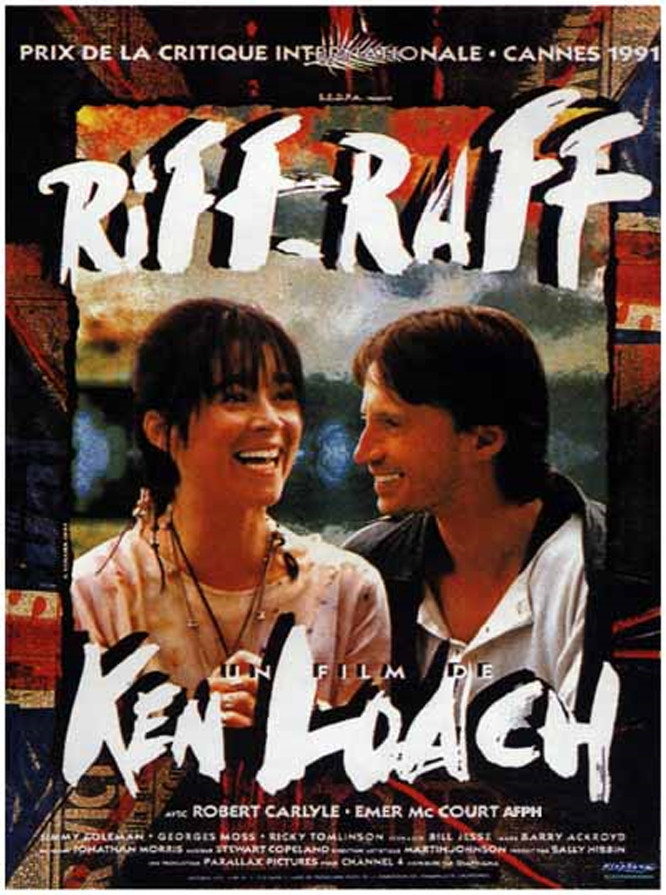

Yet “Riff-Raff” is in many ways a comedy, directed by Ken Loach, whose working-class subjects over the years have included a boy’s love for his bird in “Kes” (1971) and a police plot against liberal politicians in “Hidden Agenda” (1990). There is great humor in the scene where the leftist worker is found using a newly installed bathtub as rich buyers are shown through the flat, and humor, too, in the verbal sparring that goes on throughout the film.

In one scene, the only worker with a bank account negotiates charges for cashing the others’ checks, and the dialogue is thick with irony when they try to go back on their deal.

“Riff-Raff” was filmed in English, but the regional accents of the workers are so various that the dialogue has been subtitled anyway.