There’s a vast difference between “what happened” and “what something feels like while it’s happening.” Film is a great medium to communicate what something feels like. Yet so many films, particularly biopics, only convey “what happened,” to the point that the most traumatic events feel rote, as if the film is checking off boxes in a timeline.

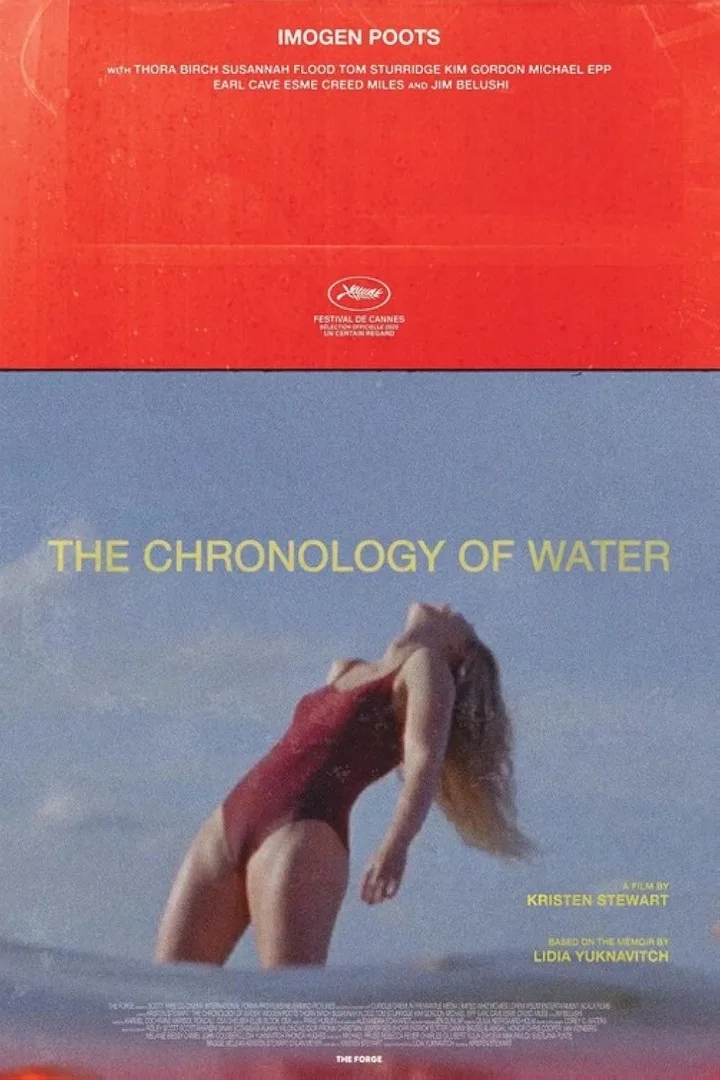

Kristen Stewart’s feature-length directorial debut, “The Chronology of Water,” based on Lidia Yuknavitch’s 2011 memoir, conveys what it feels like, and Stewart’s approach reflects not only her passion for the often complex material but her understanding of it. Stewart gets it, every bit of it, the quality of Yuknavitch’s experimental confrontational prose, as well as the continuum Yuknavitch is in as a writer, the counter-cultural ground from which she sprung. In partnership with Imogen Poots, who gives an astonishing performance as Lidia, Stewart boldly evokes the source material. There’s a collage aspect to the image placement, but Stewart is not afraid to be direct. This project has been years in the making. Stewart adapted the material, and you can feel her love for it.

Yuknavitch is like the proverbial multi-lived cat. She grew up in San Francisco. Her father sexually abused both Lidia and her older sister (who fled the home as soon as she could), and their mother was a checked-out alcoholic. Lidia escaped into competitive swimming, hoping to qualify for the Olympics. She attended college on a swimming scholarship for a couple of years, but by that point, she had descended into self-destructive behavior and addiction. Her piled-on childhood traumas were unmanaged (until she found writing). In a 2015 essay on Kathy Acker’s banned-many-times-over book Blood and Guts in High School, Yuknavitch wrote, “The decade during which I most wanted to kill myself contained coming to terms with my father’s transgressions by embarking on a sexually frenzied odyssey, a drug-induced epic world tour of counter-cultures, free-flowing abortions and aberrations and unending altered states, an abysmally failed marriage, flunking out of college, a self-loathing crescendo culminating in a daughter who died the day she was born.”

This is the searingly painful terrain of “The Chronology of Water.”

Chronology is assumed to be linear, but we don’t experience life that way. Old memories ambush us in the present. This is one way to describe PTSD: the past and present occurring simultaneously. Stewart starts her film with Yuknavitch giving birth to a stillborn baby girl, kneeling in the shower afterwards, blood pouring out of her, pooling up on the tiles, sluggishly moving towards the drain. Lidia’s knees are indented with the tile pattern, a haunting image. The event is not fully visible at first. Lidia remembers the blood on the tile, the baby’s blue fingers, and pink mouth. It’s unbearable.

The film was shot on 16mm, which adds to the overall feeling that you are looking at a memory, or watching someone’s brain flip through fragments of the past. The work of cinematographer Corey C. Waters is impressive. Many of the scenes feel improvised, as though we are dropping in on something in the middle of it. The actors all seem totally free, following their impulses spontaneously. Even with all the sexual trauma, “The Chronology of Water” manages the impossible, making a lot of the sex Lidia has as an adult look not just fun and playful, but mind-blowing and revelatory. Reclaiming your sexuality after having it stolen from you as a child is a huge, huge deal.

Stewart cast the film exceptionally well. Thora Birch is heartbreaking as Lidia’s older sister, pinched with similar traumas. The mighty Kim Gordon has a cameo as a photographer/dominatrix with whom Lidia shares a series of healing sexual encounters. Michael Epp plays Lidia’s remote father, rarely seen in full (he’s too scary to look at directly; the flick of his lighter is deafening). The actors playing the men and women Lidia gets involved with (sometimes marrying on impulse) are mostly relative unknowns, refreshing in a world of needlessly star-packed casts. The biggest stroke of genius was casting Jim Belushi as Ken Kesey.

Ken Kesey is in this? Well, yes! In the late ’80s, Lidia attended the University of Oregon (where she eventually got her Ph.D). She was invited by Kesey, a professor at the university, to join a group of graduate students collaborating with him on a novel, Caverns (published in 1989). The group lived communally and worked on the book. Kesey, by this point, was a physical wreck, but clearly a powerful teacher. Stewart doesn’t skip over this lightly. Kesey isn’t just a star cameo. This is a significant event in Lidia’s “chronology,” being “seen” by Kesey. He notices everything, including her affinity with water. “What are you, some kind of mermaid?” he growls. “Yup,” she replies. It is a meeting of the minds. I was moved by his “lecture” on the Ten Commandments, where he tosses out, casually, slightly sloshed, “The first commandment should be Have Mercy.”

In the presence of this rambling, perpetually stoned legend, Lidia grows in strength and confidence. Belushi, in a red beret, evokes the Merry Prankster in his dotage, the roughness of his manners married to the sensitivity of his perceptions. In writing classes, Lidia’s explicit work about sexual abuse drives some people from the room. Kesey doesn’t flinch. After a late-night conversation, where he puts his arm around Lidia for a little bit too long, he hauls himself up and staggers off to bed, calling back to her, his voice coming from off-screen, “You can WRITE, girl!” Poots’ face cracks open. After everything she’s been through … there it is: a way out. A way through.

There’s a tendency to call stories like this “self-empowerment narratives.” The term is too tidy and does the work of difficult writers like Yuknavitch or Acker a disservice. Yuknavitch has spoken in interviews about the challenges she faced initially in the memoir space. A memoir requires sharing trauma, and you will be called “brave,” but once you start writing about your “bad choices,” the audience will turn on you. People like Yuknavitch and Kathy Acker can’t be bothered with bourgeois niceties like this. In a 2011 interview, Yuknavitch said, “I think I was trying to infiltrate the memoir space and plant little bombs.”

Stewart’s first film as a director was a 17-minute short called Come Swim, filled with watery images and sounds, representing the interior, heartbroken experience of a man seen lying on the ocean floor. Stewart said in an interview, “I’ve been thinking about this guy on the ocean floor for like 4 years, maybe even longer.” These images are already in her, perhaps inspired by Yuknavitch’s watery work. “Come Swim” could be seen as a visual prelude to “The Chronology of Water,” in which the subconscious world dominates the conscious, and memories obliterate linearity.

Yuknavitch had to come up with a way to survive her trauma. Her life led her to the point where she can say, with confidence bordering on earned bravado: “Memories are stories. So you’d better come up with one you can live with.”

“The Chronology of Water” shows how she did that.