Steven Soderbergh‘s “Out of Sight” is a crime movie less interested in crime than in how people talk, flirt, lie and get themselves into trouble. Based on an Elmore Leonard novel, it relishes Leonard’s deep comic ease; the characters mosey through scenes existing primarily to savor the dialogue.

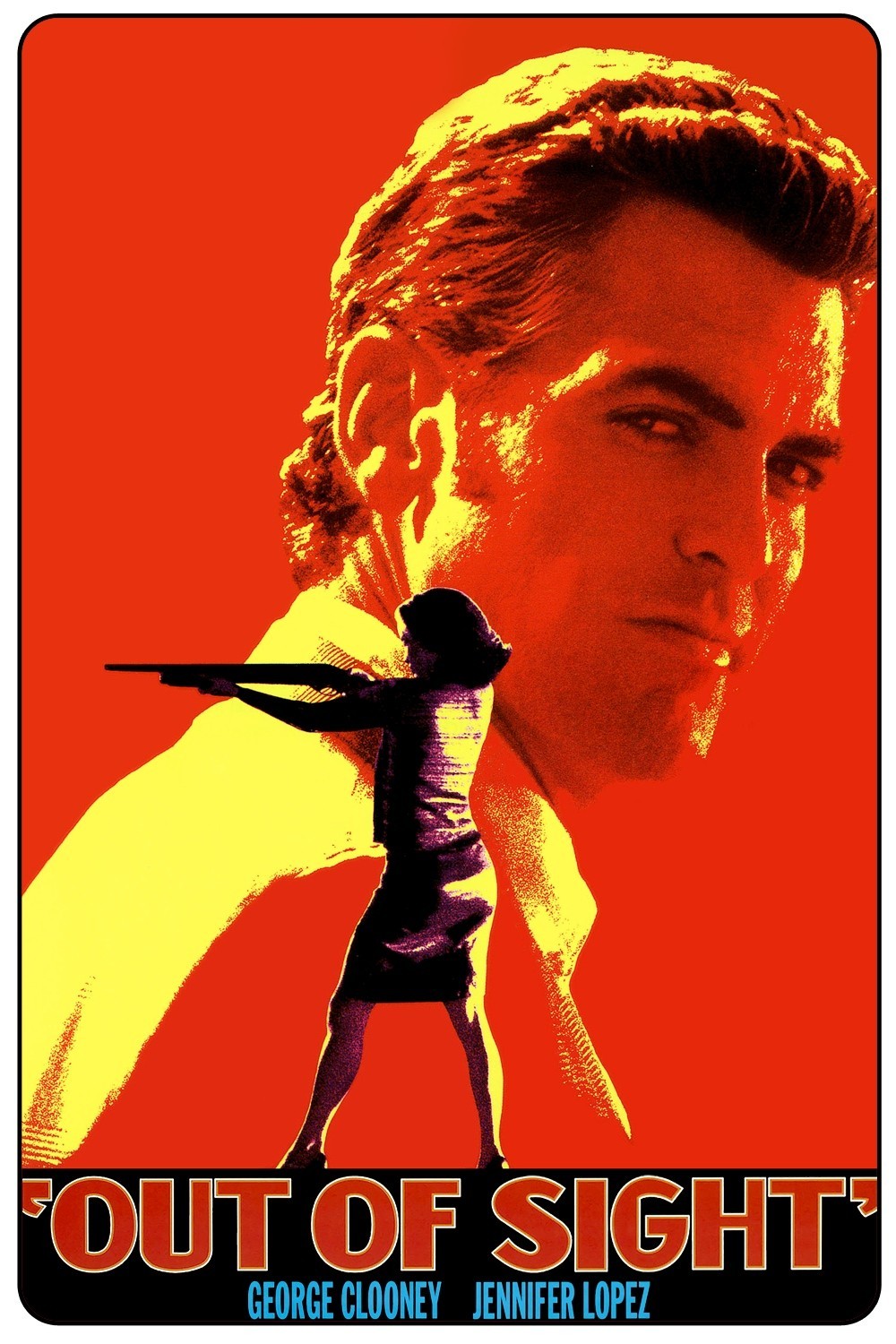

The story involves a bank robber named Foley (George Clooney)and a federal marshal named Sisco (Jennifer Lopez) who grow attracted to each other while they’re locked in a car trunk. Life goes on, and in the nature of things, it’s her job to arrest him. But several things might happen first.

This is the fourth recent adaptation of a Leonard novel, after “GetShorty,” “Touch” and “Jackie Brown,” and the most faithful to Leonard’s style.What all four movies demonstrate is how useful crime is as a setting for humancomedy. For example: All caper movies begin with a self-contained introductorycaper that has nothing at all to do with the rest of the plot. A cop willdisarm a hostage, or a terrorist will plant a preliminary bomb. “Out of Sight”begins with the most laid-back bank robbery you’d want to see, as Clooneysaunters up to a teller’s window and politely asks, “This your first time beingheld up?” How he cons the teller is one of the movie’s first pleasures. Thepoint of the scene is behavior, not robbery.

It turns out that this robbery is not, in fact,self-contained–it leads out of and into something–and it’s not even really the first scene. “Out of Sight” has a timeline as complex as “Pulp Fiction,”although at first we don’t realize that. The movie’s constructed like hypertext, so that, in a way, we can start watching at any point. It’s like the old days when you walked into the middle of a film and sat there until somebody said, “This is where we came in.” Elmore Leonard is above all the creator of colorful characters. Here we get the charming, intelligent Foley, who is constitutionally incapable of doing anything but robbing banks, and Sisco, the marshal, who had a previous liaison with a bank robber (admittedly, she eventually shot him). They are surrounded by a rich gallery of other characters, and this movie, like “Jackie Brown,” takes the time to give every character at least one well-written scene showing them as peculiar and unique.

Among Foley’s criminal accomplices are his partner Buddy Bragg(Ving Rhames, who played Marcellus Wallace in “Pulp Fiction”). He’s waiting on the outside after the prison break. In prison, Foley met a small-time hoodnamed Glenn (Steve Zahn), who “has a vacant lot for a head.” They’re highly motivated by one of their fellow prisoners, a former Wall Street leverage expert named Ripley, who unwisely spoke of a fortune in uncut diamonds that he keeps in his house. (Ripley is played by Albert Brooks with a Michael Milken hairstyle that is not a coincidence.) Then there’s the threesome who join Foley and his friends in a raid on Ripley’s house. Snoopy Miller (Don Cheadle) is a nasty piece of work, a hard-nosed and violent former boxer; Isaiah Washington plays his partner, and Keith Loneker is White Boy Rob, his clumsy but earnest bodyguard. It’s ingenious how the raid involves shifting loyalties, with Foley and Sisco simultaneously dueling and cooperating.

All of these characters have lives of their own, and don’t exist simply at the convenience of the plot. Consider a tender father-daughter birthday luncheon between Karen Sisco and her father (Dennis Farina), a former lawman who tenderly gives her a gun. And notice the scene between Buddy Bragg and his born-again sister.

At the center of the film is the repartee between Jennifer Lopez and George Clooney, and these two have the kind of unforced fun in their scenes together that reminds you of Bogart and Bacall. There’s a seduction scene in which the dialogue is intercut with the very gradual progress of the physical action, and it’s the dialogue that we want to linger on. Soderbergh edits this scene with quiet little freeze-frames; nothing quite matches up, and yet everything fits, so that the scene is like a demonstration of the whole movie’s visual and time style.

Lopez had star quality in her first role in “My Family,” and in “Anaconda,”“Selena” and the underrated “Blood and Wine,” she has only grown; here she plays a role that could be complex or maybe just plain dumb, and brings such a rich comic understanding to it. She wants to arrest the guy, but she’d like to have an affair with him first, and that leads to a delicate, well-written scene in a hotel bar where the cat and mouse hold negotiations. (It parallels, in a way, the “time out” between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in “Heat” (1995).) Clooney has never been better. A lot of actors who are handsome when young need to put on some miles before the full flavor emerges; observe how Nick Nolte, Mickey Rourke, Harrison Ford and Clint Eastwood moved from stereotypes to individuals. Here Clooney at last looks like a big screen star; the good-looking leading man from television is over with.

For Steven Soderbergh, “Out of Sight” is a paradox. It’s his best film since “sex, lies, and videotape” a decade ago, and yet at the same time it’s not what we think of as a Soderbergh film–detached, cold,analytical. It is instead the first film to build on the enormously influential “Pulp Fiction” instead of simply mimicking it. It has the games with time, the low-life dialogue, the absurd violent situations, but it also has its own texture. It plays like a string quartet written with words instead of music,performed by sleazeballs instead of musicians.