Gregory Nava’s “My Family” is like a family dinner with everybody crowded around the table, remembering good times and bad, honoring those who went before, worrying about those still to come.

It is an epic told through the eyes of one family, the Sanchez family, whose father walked north to Los Angeles from Mexico in the 1920s, and whose children include a writer, a nun, an ex-convict, a lawyer, a restaurant owner, and a boy shot dead in his prime.

Their story is told in images of startling beauty and great overflowing energy; it is rare to hear so much laughter from an audience that is also sometimes moved to tears. Few movies like this get made because few filmmakers have the ambition to open their arms wide and embrace so much life. This is the great American story, told again and again, of how our families came to this land and tried to make it better for their children.

The story begins in the 1920s with a man named Jose Sanchez, who thinks it might take him a week or two to walk north from Mexico to “a village called Los Angeles,” where he has a relative. It takes him a year.

The relative, an old man known as El Californio, was born in Los Angeles when it was still part of Mexico, and on his tombstone he wants it written, “and where I lie, it is still Mexico.” El Californio lives in a small house in East Los Angeles, and this house, tucked under a bridge on a dirt street that still actually exists, becomes a symbol of the family, gaining paint, windows, extra rooms and a picket fence as the family grows.

Jose (Jacob Vargas) crosses the bridge to the Anglo neighborhoods to work as a gardener, and there he meets Maria (Jennifer Lopez), who works as a nanny. They are married and have two children and she is pregnant with a third in the Depression year of 1932, when government troops round her up with tens of thousands of other Mexican-Americans (most of them, like Maria, American citizens) and ship them in cattle cars to central Mexico, hoping that they will never return.

“This really happened,” says the movie’s narrator, Paco (Edward James Olmos), a writer who is telling the story of his family. But Maria fights her way back to her family, sheltering her baby in her arms.

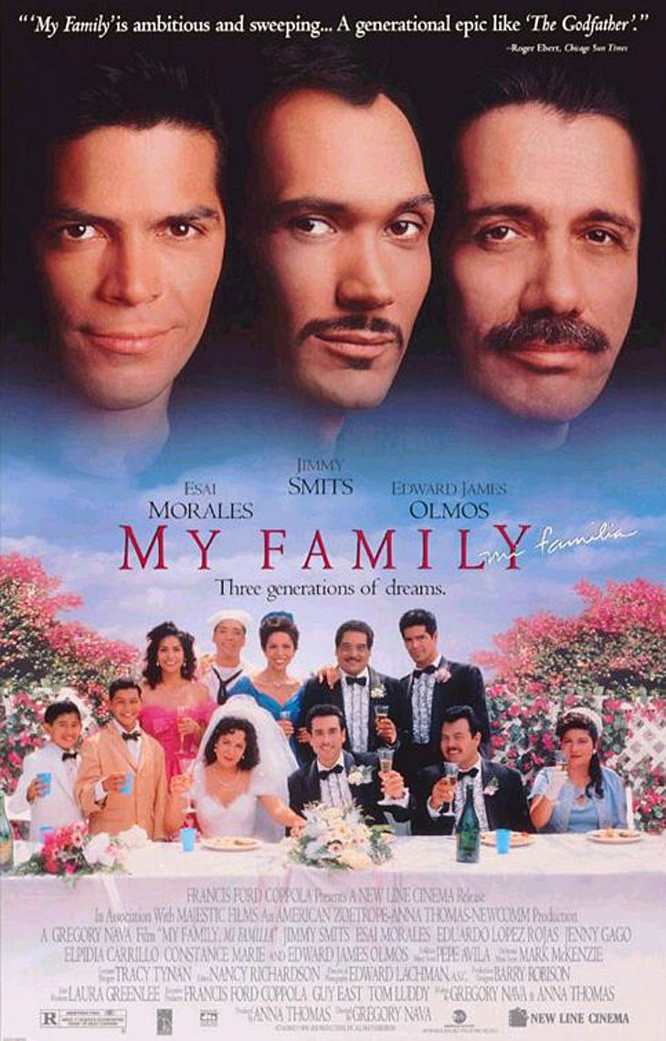

As the action moves from the 1930s to the late 1950s, we meet all the children: Paco; Irene, on her wedding day; Toni, who becomes a nun; Memo, who wants to go to law school; Chucho, who is attracted to the street life, and little Jimmy (“whose late arrival came as a great surprise”).

Nava, who is of Mexican-Basque ancestry, and his co-writer and producer (and wife), Anna Thomas, tell their stories in vivid sequences. Irene’s wedding is interrupted by the arrival of a gang hostile to the hotheaded Chucho, and as they threaten each other, Paco tells us “it was the usual macho bull- – – -.” But eventually Chucho will lose his life because of it, and little Jimmy, seeing him die, will be scarred for many years.

Toni, meanwhile, becomes a nun, goes to South America, gets “political,” and comes home to present her family with a big surprise, in one of the many scenes that mix social commentary with humor. Memo (Enrique Castillo) does become a lawyer (and tells his Anglo in-laws that his name is “basically Spanish for “Bill”).

In one of the movie’s best sequences, Toni (Constance Marie), now an activist in L.A., becomes concerned by the plight of a young woman from El Salvador who is about to be deported and faces death because of the politics of her family. She persuades Jimmy (Jimmy Smits) to marry her and save her from deportation, and in a sequence that is first hilarious and later quite moving, Jimmy does.

(Instead of kissing the bride, he mutters “you owe me” ominously at his activist sister.) This relationship between Jimmy and Isabel (Elpidia Carrillo) leads to a love scene of great beauty, as they share their stories of pain and loss.

In the scenes set in the 1950s and 1980s, Jose and Maria are played by Eduardo Lopez Rojas and Jenny Gago. They wake up at night worrying about their children (“thank God for Memo going to law school,” Paco says, “or they would have never gotten a night’s sleep”). Jimmy, so tortured by the loss of his brother, is a special concern. But the family pulls together, and Paco observes, “In my home, the difference between a family emergency and a party wasn’t that big.” Nava, whose earlier films include the great “El Norte” (1984), which won an Oscar nomination for its screenplay, has an inspired sense of color and light, and his movie has a visual freedom you rarely see on the screen. Working with cinematographer Ed Lachman, he uses color filters, smoke, shafts of sunlight and other effects to make some scenes painterly with beauty and color – and he has used a painter, Patssi Valdez, to design the interior of the Sanchez home. The movie is not just in color, but in colors.

Through all the beauty, laughter and tears, the strong heart of the family beats, and everything leads up to a closing scene, between old Jose and Marie, that is quiet, simple, joyous and heartbreaking. Rarely have I felt at the movies such a sense of time and history, of stories and lessons passing down the generations, of a family living in its memories.

Their story is the story of one Mexican-American family, but it is also in some ways the story of all families. Watching it, I was reminded of my own family’s legends and heroes and stray sheep, and the strong sense of home. “Another country?” young Jose says, when he is told where Los Angeles is. “What does that mean – `another country’?”