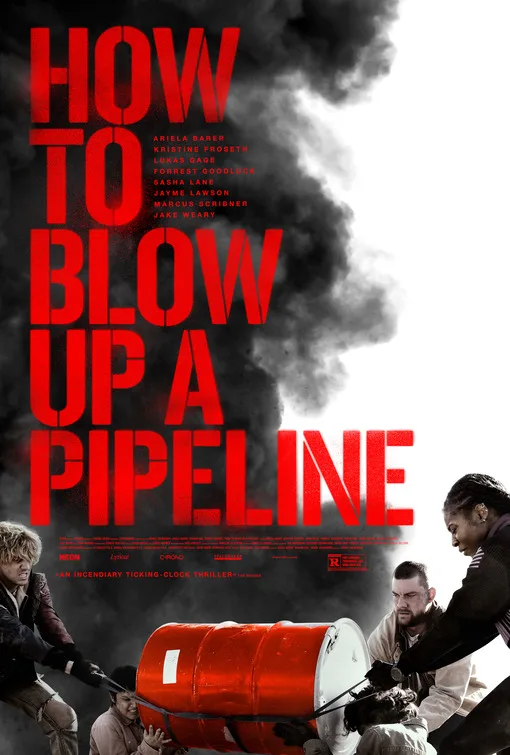

“How to Blow Up a Pipeline” is one of the most original American thrillers in years, and one that draws from a deep well of movie history as it develops its characters and sets up its plot twists. It’s likely to become controversial because of how it presents its central characters—a group of young American self-described “terrorists” trying to blow up a Texas oil pipeline to protest an array of social ills—as a legitimate though troubling force for social change, and even compares them (in scenes of conversation between the characters) to revolutionaries throughout history, including the founders of the United States of America.

Directed and co-written by Daniel Goldhaber in collaboration with Jordan Sjol and Ariela Barer, “How to Blow Up a Pipeline” adapts and reimagines a same-titled non-fiction book by Andreas Malm, which argues, among other things, that climate change is a rapidly accelerating threat to human life; that pacifist protests that try to appeal to the moral conscience of giant energy companies and their government proxies are doomed to failure and have done nothing to slow the disaster; and that targeted sabotage that is aimed at property and is careful to avoid hurting people is a justified next step. The film’s tone, pacing, and construction evoke classic thrillers from the ’70s and ’80s, from the dynamic but never showy camerawork and crisp, short, flowing scenes to the retro-synth score (by Gavin Brivik) that burbles beneath even expository moments, to the way the opening plunges audiences right into action, then judiciously flashes back to fill in everyone’s backstories and show the different reasons why each of them is drawn to such extreme action.

Jake Weary (TV’s “Chicago Fire” and “Animal Kingdom”) plays Dwayne, a young Texan who counts as the elder of the group even though he’s probably in his thirties. Jake has become radicalized against the oil company that the group is targeting because they’re trying to run a pipeline through his family homestead by abusing “eminent domain” laws that let governments seize private property for construction projects.

Xochitl (Barer, co-star of Hulu’s “Runaways”) is a quiet, intense young activist who grew up in the shadow of Long Beach, California refineries. Xochitl’s friend Shawn (Marcus Scriber of TV’s “Black-ish”) met her in college in Chicago during a meeting of students urging the school to divest from destructive and oppressive industries and funds. Another of Xochitl’s friends is Theo (Sasha Lane), who has terminal cancer from toxic chemicals and can’t afford life-saving treatment and medicine because of the train wreck that is the profit-driven US healthcare system. (This movie throws a spotlight on a lot of systemic problems and is meticulous in connecting them.) Theo’s girlfriend Alisha (Jayme Lawson) joins the group mainly out of support. The anxiety and fear that she often articulates contrasts with Theo’s commitment to the mission, which originates in the feeling that she has nothing left to lose and wants to spend the energy she has left on a cause that could help prevent others from suffering her fate.

The most electrifying character on the team is Michael (Forrest Goodluck, who played the son of the hero in “The Revenant“). Michael is a Native American from North Dakota whose people have been persecuted and marginalized for hundreds of years. He comes into the mission as a quasi-legendary underground figure, known for hassling oil rig workers and posting online videos that show him learning how to make homemade bombs from household materials. All of the actors in the film are unaffected and compelling, but Lawson and Goodluck are the breakout performers, mainly because their characters have been written in such a clear, goal-directed way, and the performers seem at times to be possessed by them. (Goodluck also channels Michael Shannon, an actor who can communicate that a character’s mind is racing in a dozen directions even when he’s handling whatever’s right in front of him.)

Rounding out the group are two self-styled Bonnie and Clydes, Rowan (Kristine Froseth of TV’s “The Society”) and Logan (Lukas Gage of “The White Lotus“). These wisecracking characters are so into each other they often seem insensitive to the pain of others and prone to distraction. (They get so amped up during the long wait for their cue to begin their part of the mission that they have sex behind scrub brush in the desert.)

Rowan and Logan are just the most obvious examples of one of the things the script gets right about the idealized anger of youth. The film repeatedly makes it clear that if this team is going to blow up the pipeline without casualties and escape to fight another day, they’ll need to stay laser-focused on the part of the plan that’s been subcontracted to them, listen to everyone around them, avoid drugs and alcohol and impulsive sex and other distractions, and stick to a schedule because one slip-up can get all of them arrested or killed. You can guess how that turns out. But anyone studying revolutionary groups will tell you this is real. A major challenge throughout the history of underground activist movements is reconciling the political with the psychological. Humans are wired a certain way, and there’s only so much they can do to control their nature.

The movie also has a self-effacing attitude towards the characters when they try to explain to themselves and others what they’re doing and why. An early group conversation (the kind that would’ve been called a “rap session” back in the era of the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground) throws historical comparisons into a verbal gumbo, touching on post-9/11 terrorism, the US Civil Rights movement (contrasting Martin Luther King with non-pacifist contemporaries) and even Jesus Christ. It’s a great scene because for all their focus and fervor, these people were in middle school ten years earlier, and still have trace elements of adolescence.

The film alternates visceral and intellectual action in a way that trades simple thrills for something more ambitious, though sometimes at the cost of momentum, often suddenly cutting away or into an extended, tense action scene to give you a bit of a character’s history.

The flashbacks are always brief, but there are moments when you can imagine an even more effective, though more traditional, film that’s entirely action-driven. (To be fair, it was wise to fill in the histories by showing the characters doing things rather than have them coughing out awkward exposition in every other scene.) The heist-movie structure lays out exactly what needs to happen, then shows how the group adapts (or fails to adapt) when, say, a surveying drone flies overhead or a couple of armed oil company property inspectors show up. There are screwups, accidents, and injuries, and by the end, everyone’s living by the Indiana Jones caveat, “I’m just making this up as I go.”

Two of the more apparent influences are Michael Mann’s “Thief,” which opens with a heist in progress, and William Friedkin’s “Sorcerer,” a remake of the classic French thriller “The Wages of Fear” about four men from wildly divergent backgrounds who come together to drive a truckload of dynamite over a rickety wooden bridge to help extinguish an oil well fire. Both movies, perhaps not coincidentally, have a score by Tangerine Dream, which for a while had a lock on scoring modern thrillers about desperate people pushed to the edge. This film is Tangerine Dreamy from start to finish. Style, story, and politics elegantly intertwine.

The result fuses technically proficient, impressively assured filmmaking to the urgently contemporary subject matter in an increasingly rare way in American commercial cinema. Goldhaber’s film is comfortable depicting these kinds of characters in a way that lets the audience decide how to feel about them. It is not afraid of seeming to endorse their ideas.

Now playing in theaters.