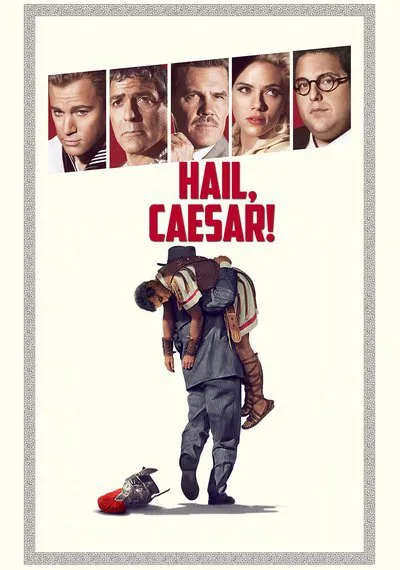

It’s been some time since Joel and Ethan Coen have made a full-out comedy. The producing, writing, and directing (and editing, too, albeit under an assumed name) brother team’s last three films, “A Serious Man,” “True Grit,” and “Inside Llewyn Davis,” certainly haven’t lacked for funny moments. But “Man” was an apocalyptic riff painted on two inches of ivory, “True Grit” a rousing adventure that gradually mutated into a memory play about loss and mortality, and “Llewyn Davis” was at least in part a deeply sad story of inescapable existential failure. In other words, pretty heavy s**t. Their new film, “Hail Caesar!” is an exhilarating switchup: A comic fable that’s both deftly clever and irrepressibly goofy. It is also, from stem to stern, the sweetest and sunniest film the Coens have ever made. Although you might not guess that from its opening shot, of a sculpture of a crucified Christ figure in a Catholic church. Bear with me.

Set in an unspecified period in 20th-century Hollywood some time between the end of World War II and … well, certainly before 1960, although the movie is meticulously determined in certain ways to be as ahistorical as possible, “Hail Caesar!” depicts 28 or so hours in the life of one Eddie Mannix, played here with a beautiful combination of no-nonsense gruffness and tortured tenderness by Josh Brolin. The Coens took the name of their character from the real-life name of one of the more villainous figures in backstage Hollywood history (he was played by Bob Hoskins in the much darker Tinseltown riff “Hollywoodland”), but this entirely fictional Mannix is a harried ordinary-joe exec, “Head Of Physical Production” for a studio called Capitol Pictures. Capitol churns out conscientiously produced but hopelessly schlocky big pictures in a variety of genres, from Biblical epics to cornball oaters.

On this day in the life, Mannix has a number of big problems to contend with. The front office wants Mannix to “promote” singing cowboy Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich) from B-western star to romantic comedy leading man, much to the confusion of the eager-to-please Hobie himself, and the consternation of his new, exacting director, self-styled studio auteur Laurence Laurentz. The aquatic musical star DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson) is newly pregnant, which is making her mermaid costume painful to wear, and on top of that, she’s not sure if she’s interested in marrying the father of her child, a refusal that would constitute a potential PR gaffe for a studio that prides itself on an All-American image. A pair of twin gossip columnists (both played by Tilda Swinton) are demanding answers to awkward questions and threatening to go public with an awkward story about the studio’s biggest matinee idol, Baird Whitlock (George Clooney). Finally, and most crucially, Whitlock himself has been kidnapped from the set of his Biblical epic, by a group of disgruntled Communist screenwriters who call themselves “The Future” in their terse ransom note. In the meantime, Mannix must deal with his personal demons: he’s a devout Catholic who almost compulsively goes to confession, much to the exasperation of his otherwise kindly and indulgent confessor. He frets over having told his loving wife that he’s going to quit smoking, and then sneaking some cigarettes during his stress-filled day. He’s also being aggressively courted by a recruiter from Lockheed, who tempts Eddie with a vested position, the promise of saner hours, and the chance to involve himself with something “serious.” How serious? This character shows Eddie a shot of a recent H-bomb test at Bikini Atoll. “Lockheed was there,” he intones. You can tell this character is the devil because he always offers Eddie a cigarette when they meet.

The Coens being the Coens, they cannot, or rather do not, resist the temptation to take what were and remain serious matters not-terribly-seriously; in their funhouse mirror mashup of 1950s Hollywood, the ostensible Red Scare was no “scare” at all but rather a Cold War component in which a big Hollywood star might conceivably defect to play “Soviet Man” for Mosfilm. Once in the hands of his kidnappers, the amiable but boneheaded Whitlock—poor George Clooney, playing his fourth idiot for the Coen Brothers, is stuck in a goofy Roman Centurion costume and haircut for the whole movie—is instructed in Marxist logic by no less a personage than Dr. Herbert Marcuse himself. (Okay, he’s only referred to as “Professor Marcuse,” but actor John Bluthal is made up to look like the actual figure.) All this cockeyed revisionist history may inspire scary thoughts of Steven Spielberg’s (ostensibly) disastrous 1979 comedy “1941.” And to tell you the truth, there is more than a bit of broad, blithely unserious japery at play here. One also recalls “The Hudsucker Proxy” and the Sam Raimi-directed, Coen-Brothers-co-written “Crimewave.” But the Coen Brothers have funnier jokes than Spielberg did, and they also know their real stuff at an almost dangerous level—in the new commentary to “Inside Llewyn Davis” on the Criterion Collection disc, writers Robert Christgau and Sean Wilentz marvel at a throwaway Max Schactman reference in the movie that flew over the heads of 99 44/100th percent of viewers, and here they present an American Communist Party membership card replete with a Gus Hall signature.

You can miss or ignore so many of these details and still enjoy the exquisite clockwork mechanism of the movie’s plot, and/or the various pastiches of old movies it offers up in differing manifestations. The goofily, cluelessly homoerotic “No Dames” musical number, starring a game-as-always Channing Tatum, is a highlight, as is the near-pornographic whale-spouting imagery of the Busby-Berkeley-inflected Johansson-showcasing water ballet. (Around the time of “The Big Lebowski” I asked the Coens if they were influenced by the Technicolor musical films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and they were characteristically cagey in response; here they acknowledge their fandom by scoring the water dance to a bit from Offenbach’s “Tales of Hoffmann.”) The movie’s performances are all spectacularly rewarding, but Ehrenreich practically steals the picture as the completely ingenuous singing cowboy who ain’t quite as dumb as he seems, not by a long shot.

The movie makes light of the dialectic as explained to Baird by Marcuse, but it also, in its tricky way, continually invites/compels the viewer to use it. Eddie Mannix is a good man who is very good at his job—but his job seems to be manufacturing schlock. People enjoy schlock, but schlock is arguably an agent of The People’s oppression, so … anyway, one needn’t go on. Suffice it to say that in the cosmology of the delightful “Hail Caesar!”, regardless of the conclusions to which dialectical thinking may lead, acceptance is the key, and Hollywood, while “problematic,” is more a force for good than the military-industrial complex can ever hope to be. And, finally, doing the right thing is an instinct shared by both company men and singing cowboys, for whatever that’s worth.