We’ll fly to the stars …Journey to Mars …And find our breakfast on Pluto. I heard this song performed in London by a blind man in a pub on Portobello Road in the early 1970s, and remembered it during Neil Jordan’s new film. His hero Patrick Braden, known as Kitten, would have heard it at about the same time, and needed to, because he needed all the cheering-up he could get, and usually breakfast, too. “Breakfast on Pluto” tells the story of an Irish orphan, left on the steps of a priest’s rectory and raised by a strict foster mother. Patrick discovers his identity at an early age. One day the woman finds him trying on her dresses and shoes.

“I’ll walk you up and down the streets before the whole town in disgrace!” she screams.

“Promise?” says Patrick.

He is then about 10. Too young to have such feelings and smart answers? Not if you have seen Jonathan Caouette’s documentary “Tarnation,” which contains a home movie of Jonathan in drag at about the same age, with something of the same personality. Patrick decides that his name is Kitten, insists on being called by it, and is not a boy trapped in a girl’s body but a boy trapped in a transvestite’s body — or, more accurately, a boy trapped in a world he desperately wants to escape, and using his imagination to reinvent himself and escape it. He is, as they say, not like the other boys.

The enchanting and hopeful “Breakfast on Pluto,” adapted by Jordan from a novel by Patrick McCabe, has a hero who is a little mad and a little saintly. Many saints insist on living in their own way regardless of what the world thinks. Some climb trees or pray in caves. Some work among the poor. Some, like Kitten, insist on optimism in the face of absolutely everything. In his case, it could be sainthood, could be denial, could be insanity. Whatever it is, Kitten so stubbornly insists on it that motorcycle gangs, London cops and IRA killers all realize that they can kill him, but they can’t change him.

The movie is like a Dickens novel in which the hero moves through the underskirts of society, encountering one colorful character after another. Kitten believes his birth mother may have moved to London. His only clue is that she looked like Mitzi Gaynor. Of course Kitten would know who that was. In the course of his journey to find her, he sings with a rock band, becomes a magician’s assistant, is a suspected IRA bomber and is reduced to street prostitution, although he handles it with a kind of dreamy denial. The movie becomes a series of seductions, with the goal not sex but acceptance.

Consider that Kitten is unluckily in a London pub when it’s bombed by the IRA. The cops suspect him as a cross-dressing bomber, and interrogate him for a week, not gently. At the end of that time they give up and accept him for who and what he says he is. A little later, one of the same cops who beat him sees him working the streets, knows Kitten is no match for the life, drives him to Soho, drops him outside a peep show and says, with real concern, “Get a job here. It’s safe and it’s legal.”

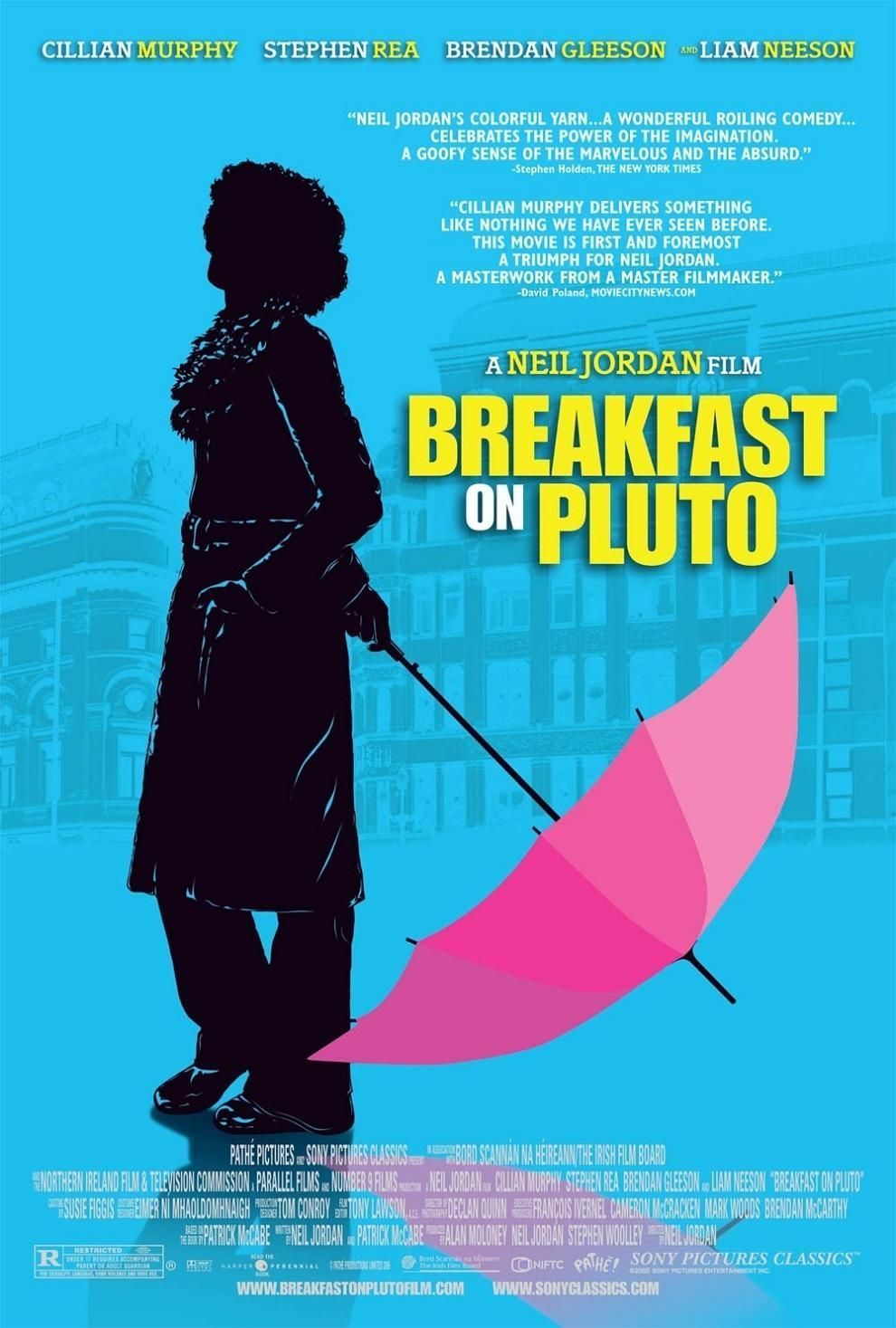

Kitten depends on the kindness of strangers. Played by Cillian Murphy with a bemused and hopeful voice, he meets such characters as Billy (Gavin Friday), leader of the scruffy rock band Billy Hatchet and the Mohawks, and soon Kitten is onstage as a squaw, helping out during the performance of “Running Bear.” Billy falls in love with him, but eventually “the band thinks the squaw is not working out,” and Kitten finds a job being sawed in two by a magician named Bertie (Stephen Rea). In Jordan’s “The Crying Game,” Rea fell in love with a cross-dressing hairdresser. But no one is deceived by Kitten, who doesn’t care if you think he’s male or female, as long as you think he’s Kitten.

That’s the part of the story Dickens would have agreed with. His heroes, from Pip to Oliver Twist to Nicholas Nickleby to David Copperfield, travel bleak landscapes of gruesome betrayal and disappointment and meet villains of every description but never lose their innocence. Dickens also would have enjoyed the story’s use of melodrama and improbable coincidence, and the way the hero befriends and is befriended just when it’s needed the most.

Consider Father Bernard (Liam Neeson), whose rectory steps are Kitten’s first home. The priest is one of those good souls bumbling through, doing what good he can. And John-Joe (Brendan Gleeson), a streetwise hobo who shares what he has. And Charlie (Ruth Negga), a black girl who becomes Kitten’s closest friend. And consider the story of how Kitten does, or does not, find his mother, or Mitzi Gaynor, or whoever, and what he finds out then.

“Breakfast on Pluto” is being included in earnest analytical articles about this being the season of homosexuals (“Brokeback Mountain“), transsexuals (“Transamerica“), transvestites (this movie), or all three (“Rent“). As a “trend,” this means absolutely nothing, although as a coincidence it is worth notice, however slight. What these titles have in common with many other good current films are characters who are given the challenge to be true to their own natures, and either rise to the occasion or descend into misery.

Kitten has less to do with sexual unorthodoxy than knowing what you must be and do, and bring and doing it: Characters like those played by Terrence Howard in “Hustle & Flow,” Anthony Hopkins in “The World's Fastest Indian,” Amy Adams in “Junebug,” Naomi Watts in “Ellie Parker,” Miranda July in “Me and You and Everyone We Know,” Tommy Lee Jones in “The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada,” Charlize Theron in “North Country” and the Great Ape in “King Kong.” This drive toward individualism is an encouraging counterforce to the relentless team spirit that seems to drive so much unhappiness in our society. While it is true that in some times and places Kitten would be murdered (the fear that haunts Ennis in “Brokeback Mountain”), it is also true that Kitten might be given a pass by dangerous characters who either recognize a kindred independence, or envy it.